Friday, June 22, 2012

SIDELINE: A LENA DUNHAM MEA CULPA

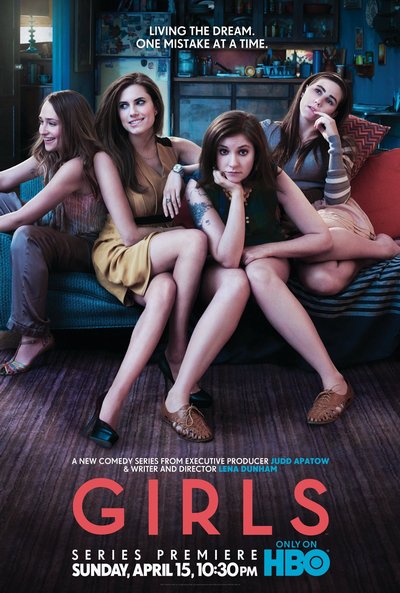

When I ran my review of Tiny Furniture on this blog, I added a coda dismissing Lena Dunham's HBO series Girls. Based on the pilot, it appeared we were in for just a retread of all the irksome traits of her full-length feature: self-important, entitled myopia magnified to a level of false importance. Worse, as the series sank in, it started to look like Girls was going to merely be a post-college Sex and the City [review]. There was the promiscuous blonde girl, the virginal brunette, the uptight responsible one, and the neurotic writer doing her best to fail at relationships. Yeah, I know, this is such a Charlotte thing for me to say, but I didn't like it.

The debate kept going elsewhere, however, and it got heated enough and was interesting enough that I felt compelled to give Girls a chance and follow my own three-installment rule. This rule says that any piece of art, particularly serialized art, deserves three chapters or episodes or issues to find its footing and let you know what it's all about. If a show or a comic book or whatever can't hook you in three, then you have every right to move on.

And sure enough, by episode three, a disarming vulnerability had crept into Girls. Dunham not only revealed a larger capacity for examination than she'd previously shown, but it also became evident that the earlier self-involvement had possibly been defensive and, in reality, she was becoming increasingly aware of her own place in the world. Better yet, she understood the people around her and could, indeed, dig into the lives of the characters she was bringing along with her for this endeavor. As the writer, director, and star, it would have been easy to make Girl rather than Girls, but over the coure of the first season, all the supporting cast got their due and grew into meaningful people.

By the finale, Dunham had done what she could not do in Tiny Furniture: bring her fictional persona to a point of new understanding that allows for a true emotional breakthrough. And not one just tacked on, but earned. Her character, Hannah, had gone from someone I rebuked as being terrible to someone I actually empathized with. She's still terrible--and in two different, powerful scenes in the last two episodes, other characters tell her not only how terrible she is, but exactly why--but yet, aren't we all?

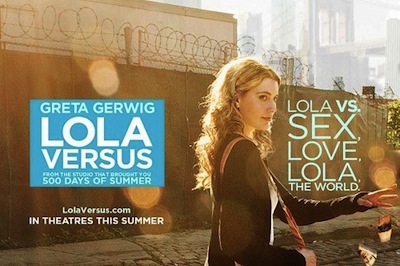

I bring this up now because, in reviewing Daryl Wein and Zoe Lister Jones' Lola Versus, I found myself not only thinking of Dunham's work, but also Jennifer Westfeldt's Friends with Kids [review]. The one thing all of these cinematic efforts have in common is that they portray the lives of (mostly) white people living comfortably in New York, walking a strange and achingly thin line between self-serious drama and satire, seemingly oblivious to how good they have it. In Lola Versus, do all those references to Kombucha and vegan food and the like amount to a critique of trend chasing or does all of these things fall into the characters (and, by default, their creators) being exactly what they pretend they aren't? (Expect this to come up again this summer when the Lee Toland Krieger-directed Celeste and Jesse Forever lands in theaters [review].) Striking a balance between emulation and exhumation is something Whit Stillman regularly pulls off (his recent Damsels in Distress is a very good example), managing a sort of erudite Fitzgeraldian tone of simultaneous adoration and amusement. It's also something I think Lena Dunham has now figured out. The jury is still out on the rest.

Anyway, for what it's worth, I was wrong about Girls. I take back what I said. Mea culpa, Lena Dunham.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment