As 2012 comes to a close, this trio of reviews of Seijun Suzuki movies actually catches me up for the weeks I missed in November. This marks four full years of providing one new review to this blog a week. That's a lot of writing and a lot of movies.

I picked Take Aim at the Police Van from the Eclipse Nikkatsu Noir set because it was the only remaining Suzuki film in my collection that I had not yet watched. It's interesting that my viewing over the past two days has gone in reverse chronological order. I am not sure why Criterion decided to number Tokyo Drifter [review] and Branded to Kill [review] the way they did, but with this 1960 mystery/drama thrown in, the effect for me was to see Suzuki's style get more normal as I progressed.

Coming some six years before Tokyo Drifter, Take Aim at the Police Van is a more conventional genre exercise than the director's later films. It begins with a violent attack on a prison transport van. Suzuki builds tension by having road-sign warnings repeat over and over, moving faster and making the viewer nervous with all their cries of "Caution!" It also doesn't help that we know that up ahead a sniper is waiting. When the van approaches his hillside vantage point, he opens fire, killing two of the prisoners. It was a concentrated attack.

The guard on that run, Daijiro Tamon (Michitaro Mizushima), is held responsible for the assault, and he is put on six months leave. Rather than stay at home and sulk, Tamon decides to look into what really happened all on his own, thus transforming himself into a traditional fictional investigator, doggedly pursuing his goals despite the warnings and the dangers. Suzuki and scriptwriter Shinichi Sekizawa see Tamon as belonging to a western tradition, and even make reference to Ellery Queen and other mystery writers who concocted similar stories with equally committed characters. Tamon begins his case by finding one of the shooting survivors, a low-level crook named Goro (Shoichi Ozawa) who was due to be released on bail the day of the incident. Goro's behavior during the attack makes Tamon think he knows something.

Naturally, pulling on this first thread causes many others to unravel. Tamon follows Goro out of town, where the mistress of one of the dead prisoners and Tsunako, the girl who bailed Goro out (Mari Shiraki), are working as strippers in an illicit brothel. Their involvement leads the prison guard to a human trafficking ring with ties to a mysterious, possibly fictitious big boss named Akiba. More people end up dead, some thought dead end up alive, and Tamon maybe has a thing for one of the possible suspects (Misako Watanabe). Yuko's father runs the "talent agency" that books the girls, and she's taken charge of the business since her old man got sick. She also knows archery, which is interesting since the dead stripper was shot in the heart with an arrow!

Take Aim at the Police Van takes a tried-and-true approach to building its mystery. For every answer Tamon finds, he also uncovers a few more questions. More players join the story, and the cast builds to the point where he doesn't really know who is going to pop out from which shadow next. Mizushima plays the role pretty straight. He's always looking forward, rarely indulging in sentiment or any emotion that might alter his course. He's an older man, and seeing him tangled up with so many young girls creates an amusing incongruity. Tamon is no white knight, but he will get the job done.

By the time we get to the climax, just about any of the crooks could be Akiba. Tamon has formed an uneasy alliance with Yuko, particularly after the two of them are nearly burned alive in a gasoline truck by the sniper, and he also takes a liking to Tsunako and wants to get her out of whatever trouble Goro might have gotten her into. Motor vehicles and motorways prove dangerous throughout the film. There is a chase on a cliffside highway and later Tamon is nearly run down by coordinated vehicles coming from two different directions. Goro also humorously provides the movie with its second roadside omen: he has a backpack that says "No U-Turns." There is no turning around, there is only forging ahead.

It makes for a sublime kismet, then, that the final shootout in Take Aim at the Police Van goes down in a trainyard. Buses and cars are unpredictable. They crash and they roll, and their course is subject to human control. Trains follow a track. They are reliable and they are sturdy. Their destination can't be changed easily. For some, this will be fatal; for others, salvation. Trains are also the industry of an older generation, one that Tamon can identify with. And perhaps that is why he is as reliable and as dedicated, as well. The young hoods have their flashy cars, but he identifies with the rails, getting the job done and never deviating from the predestined route.

BONUS SEIJUN SUZUKI REVIEWS:

* Detective Burea 2-3: Go to Hell Bastards! (1963)

* Tanuki Goten (Princess Raccoon) (2005)

And one from the archives, part of a group of reviews I did for my old column "Can You Picture That?" on OniPress.com. This one was reviewed alongside Onibaba, and that portion was reprinted here.

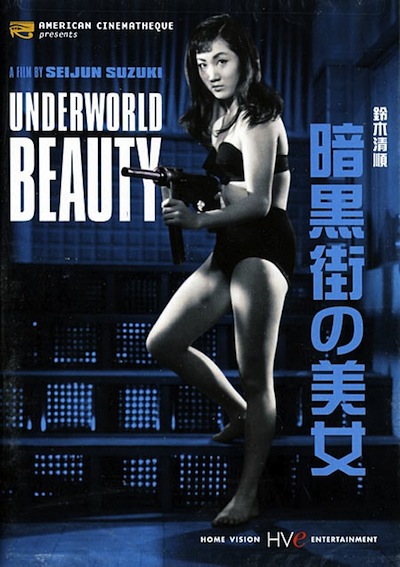

Underworld Beauty (1958): Speaking of cover art, I initially thought that Seijun Suzuki's 1958 yakuza movie, Underworld Beauty, would be a perfect companion to Onibaba. A beautiful woman dramatically posing with a machine gun! Yes! Only the cover art is entirely misleading. Akiko (Mari Shiraki) never picks up a gun inUnderworld Beauty. I was fooled by marketing!

Thankfully, Underworld Beauty is an entertaining film even without a pretty young thing shooting up the bad boys. Released by Home Vision Entertainment along with a spate of other Suzuki films, Underworld Beauty hints a little bit at the scattershot editing style that, a decade later, got Suzuki fired and branded "incomprehensible" (the way sometimes the story jumps from point A to point C pales next to the supersonic speed Branded to Kill travels at). Overall, though, it's a pretty straightforward crime picture with a cynical edge reminiscent of Sam Fuller.

The plot is simple: Miyamoto has spent three years in prison. In that time, he has managed to keep his mouth shut, giving up neither his yakuza bosses nor the hiding place of the jewels he stole. Feeling guilty about his partner, Mihara, who was partially crippled in the heist, he decides to work through his old boss and sell the diamonds, giving the money to his friend. Only someone attempts to steal the stones at the sale, and Mihara ends up swallowing the jewels before leaping off a building to escape. In the wake of his death, Miyamoto and Akiko go up against the yakuza and Akiko's effete, mannequin-manufacturing boyfriend, working through a maze of double-crosses to establish ownership of the three shiny jewels.

What sets Underworld Beauty apart from standard crime films of the period is the clash of the old school gangster (Miyamoto) and the wild-child, idealistic teenager (Akiko). It's never more clear than when the dark-suited hoods step into the bossa-nova rock-and-roll nightclub filled with kids dressed in light colors. The crooks are like brick walls, while the teenagers are much more petite. At one point, one of the bad guys shoves the fresh-faced bartender away from the bar and he practically launches into the air. Thus, the central conflict becomes whether or not Akiko can step up and act maturely. Can she and Miyamoto find common ground, and will it carry them through the classic crime-doesn't-pay ending? (Side note: It's interesting to compare the rather milquetoast version of a rock club in Underworld Beauty to the seedier nightclub in Akira Kurosawa's High and Low [review] five years later. The former is definitely the bobby-soxer '50s version we see in a lot of period entertainment, whereas the latter's sweaty opium den vibe showed the false innocence was already crumbling.)

No comments:

Post a Comment