Sabu's sophomore feature was a more stodgy affair than the first, and it also saw him relegated to more of a supporting role next to British star Roger Livesey (I Know Where I'm Going, The League of Gentlemen [review]). Following just a year after the success of Elephant Boy, The Drum (1938; 98 minutes) was Zoltan Korda's first adaptation of an A.E.W. Mason novel, a precursor to the more artistically successful The Four Feathers [review], the epic adventure that would follow immediately after. (Interesting side not, Livesey played the role of Harry as a child in the second film version of The Four Feathers in 1921; he was not in Korda's remake.)

Set in India at a time of political upheaval, The Drum features Livesey as the enterprising Captain Carruthers and Sabu as Prince Azim, a naïve but earnest young ruler who befriends the colonialists. He is particularly fond of a bratty young drummer (Desmond Tester) in the British Army band and of Carruthers' kindly wife (Valerie Hobson, Contraband [review]). When Azim's uncle, the appropriately named Prince Ghul (Raymond Massey in brownface), kills the boy's father, the child prince must go into hiding, biding his time until the British can overthrow Ghul and put him back in power.

Okay, am I the only one who thinks of the The Lion King [review] here? Is that bad of me?

To be fair, it's a pretty common plot, and The Drum obviously appropriated it first--though it's disappointing in execution here because the embattled prince isn't so much passive as he is incompetent. Sabu isn't nearly as comfortable onscreen in The Drum as he was in Elephant Boy; his "serious" acting features a lot of squinty eyes and pursed lips. He is best when joking with Carruthers or the drummer boy, and the way Azim kowtows to the white men who taught him to be "civilized" leaves a somewhat sour aftertaste. Far more interesting, actually, is the villainous Ghul, who, like Skar in The Lion King (sorry!), is not entirely wrong. There is something rotten in India, and some question as to the rightful heir's ability to rule. Unlike Skar, however, Ghul also has an element of nobility. His designs on the throne aren't entirely selfish. Korda and screenwriter Lajos Biro's attempts to ridicule Indian beliefs and customs backfire. Ghul ends up looking like a defender of his country's ethnic traditions, refusing to accept the British charges of barbarism.

Two positive things about The Drum: (1) Georges Perinal and Osmond Borradile's Technicolor photography is lovely and vivacious (even if this print is a little faded and beat up). The sets and the costumes have an exotic opulence that must have been thrilling to see in the late 1930s, and still has charm now. (2) The climactic battle is impressively staged and daring in complexity. The crowd scenes before and during are huge, and Korda doesn't show a heavy hand in dictating how the throngs behave. The old tag line for the film boasted a cast of 3,000, and the authenticity of the mob goes a long way to make that claim appear to be true. Plus, Roger Livesey is surprisingly badass manning a Gatling gun.

Next up for Sabu was the Michael Powell-directed, Korda-produced The Thief of Bagdad [review] in 1940 before rejoining Zoltan in 1942 for their second version of a Rudyard Kipling story. Jungle Book (106 Minutes) is Sabu's most enduring work, as well as the most famous live-action version of the classic adventure tale--and with good reason. Sabu has not only matured as a man and an actor, developing into a physically agile performer, but Korda's film, as shot by W. Howard Greene and Jack Okey, is a visual marvel. The team creates a thriving Technicolor jungle, filled with lush plant life, exotic animals, and the remnants of man's beautiful folly.

Sabu plays Mowgli, a boy lost to the wilds after a tiger attack leaves his father dead. Adopted by wolves as a toddler, he returns as a teen to rejoin his village, much to the delight of his mother (Rosemary De Camp) and the suspicion of the town swindler, Buldeo (Joseph Calleia), who also serves as the storyteller whose own tale frames Mowgli's.

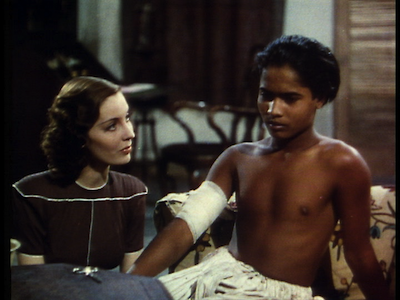

Mowgli adapts to village life, learning English and the baffling ways of society. Money holds little interest for him, though it buys him a knife to hunt the tiger, Shere Khan, who has vowed to kill him since he was a baby. He also takes a shine to Buldeo's daughter (Patricia O'Rourke), giving the man all the more reason to hate the jungle boy. Worse, Mowgli leads the girl to a grand treasure, only to leave it where it has remained hidden for decades rather than succumb to the evil that jewels and gold inspire. (It's ironic, given most Western iconography, that a snake warns the boy away rather than leading him into temptation.) This sets up Jungle Book's climax and sets up the foundation for its theme of man's greed and superstition being his downfall.

The story of Jungle Book is familiar to most people, though again we must invoke Disney, as the common memory often goes back to their animated version

More impressive than the animal wrangling, though, are the sets. Korda uses a combination of matte paintings and physical sets to bring to life a colorful jungle setting. There are plants with fiery red leaves and giant blue statues and light tumbling through the trees that takes on astonishing purple hues. Sabu runs through each attractive set piece as a free spirit, utterly convincing as the wild boy who swings on vines and howls at the moon. Indeed, while the trained British actors come off as overly mannered and comical through most of the movie, acting down to the material, Sabu is perfectly comfortable in his chosen environment.

All three of Sabu's first movies with Zoltan Korda are now part of Criterion's Sabu - Eclipse Series 30 boxed set. I'd like to believe that Elephant Boy and particularly Jungle Book could still stoke the imagination of young viewers. Despite our technological advances, one assumes the untamed forests still hold some sway over our basic human instincts. This set would make a nice companion with the other Criterion younger viewer titles, namely Albert Lamorisse's The Red Balloon [review] and White Mane [review], and Bill Mason's Paddle to the Sea[review], all of which feature children interacting with the wonders of the natural world in exciting, yet vastly different, ways.

This disc was provided by the Criterion Collection for purposes of review.

No comments:

Post a Comment