Storytelling is a commodity.

To make a movie is to take a story, confine it in a box--be it rectangle or square--and use it to buy your way into people's lives. It's probably why we get so passionate about the films we love, we've agreed to trade a part of ourselves to make room for them.

In the world created in the 1940 Thief of Bagdad remake, stories are very important. They can be used to save someone's life or to condemn it. The film itself is like a storybook, containing many tales under one cover, some with positive moral lessons and some with truly negative outcomes. The blind man Ahmad (John Justin) uses verse to attract alms and spins a longer yarn about his life as a King to bide his time and buy himself some time in his enemy's home. Within his story, there are other stories, and he is even listening to one when his usurper, Jaffar (Conrad Veidt), catches him unaware. Actually, Jaffar uses a story to set his trap and then uses another to close it. The tale of Ahmad's grandfather traveling out among his subjects to learn more about them is manipulated to convince Ahmad to do the same, and then Jaffar's fib branding the monarch a madman seals his fate. Ironically, in between the two, Ahmad sits down to hear a story about himself and how the toppling of his tyranny has been foretold in prophecy. All these narratives have been his undoing.

The Thief of Bagdad is like a cinematic version of a framed photo of a man holding a framed photo--the very same photo that is in the larger frame. And in that photo, another man and another photo, and on and on. In the movie, the Sultan of Basra (Miles Malleson), a collector of toys, has a replica theatre that contains miniature puppets that perform for him exactly the same way every time he opens the tiny doors. Though, in the movie, these aren't puppets, but real acrobats, and what we see is a miniature film within the film. Like the photo in the photo, the story inside the story, this is a movie in a movie.

Though The Thief of Bagdad is directed by three men, most forget to mention Ludwig Berger and Tim Whelan, and the picture is commonly credited to Michael Powell as director and to producer Alexander Korda as the lord and master. Powell, who would go on from here to begin a long-lasting and joyous collaboration with writer Emeric Pressburger, seemed to have a particular fascination with the fabric of story. In plenty of his other movies, the larger narrative contains smaller ones, be it David Niven accounting for his life on a Stairway to Heaven or the ballet company gripped by personal drama finally putting on their production of The Red Shoes. Thus, making a movie that uses as its source One Thousand and One Nights (a.k.a. Arabian Nights), the granddaddy of all story-within-a-story narratives, makes perfect sense for Powell. It's also notable that it marked his shift from realistic movies like The Edge of the World

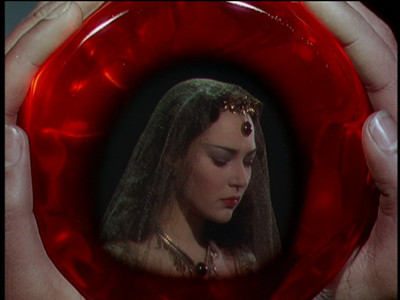

In addition to the performers inside the Sultan's toy theatre, there are many instances when one character spies the actions of another through a frame. This works in tandem with the eye motif, which Michael Powell is often credited with introducing into The Thief of Bagdad. It begins with the zoom on the eye painted on the hull of a boat at the start of the picture, and comes up again in both how Jaffar performs his magic and the poetic injustice visited on Ahmad when he is blinded. Multiple times, characters are instructed to look with their eyes or are asked why their eyes are closed. When parted, Ahmad and his Princess (June Duprez) long to look upon one another again, and the difference in worldviews between the twisted Jaffar and the romantic Ahmad is summed up in how they view the object of their desire. The Princess is all Jaffar can see because he can't have her, and though Jaffar insists that when her lover regains his eyesight, Ahmad will see that there are plenty of women all over the world, when the King can see again, he only has eyes for one special lady. Even the little thief Abu (played by Sabu) is told that the key to miracles is seeing the world with the eyes of a child. It's a proper metaphor for the new mythology of moviemaking. The magician uses his eyes to perform his magic, his audience uses theirs to see it. It's a back-and-forth between filmmaker and viewer, here seen as a glorious positive--even if much later in his career Powell would question what we are all looking at in his controversial Peeping Tom.

This eye imagery is probably best represented by the All Seeing Eye, a jewel that Abu steals from a sacred temple, where it has rested for 2000 years. Through this jewel, he is able to find the lost Ahmad, and Ahmad is able to look across the world at his Princess. When the jewel is shattered, it becomes Abu's passage into a realm of miracles. Shattering the eye destroys the collective blindness that afflicts modern society and keeps its denizens from seeing magic. It is also cinema shattering the bonds of centuries of storytelling convention, forging the way for something new and different. You won't just hear or read about carpets flying, you will see them!

Once Ahmad's account of his past--his betrayal by Jaffar, falling in love, Abu being turned into a dog, the Princess falling into a deep trance--catches up with his present, the movie shifts out of campfire mode and remains in the present, moving forward along one line for the duration of the movie. For its second half, Thief of Bagdad becomes everything it was meant to be, its own dazzling story. This is an adventure picture, after all, meant to give moviegoers some thrills and show off the special effects technology being developed at the time. Some of those effects look quaint today, now that we are more familiar with bluescreen and CGI has replaced models and puppets with 3-D constructs. It's not that hard to peer past the veil of fantasy when tiny Abu shares the screen with the giant Djinni (Rex Ingram), yet even jaded viewers should be able to see how playfully this engages the notion of movie illusion. It's almost better that it looks fake, and to get too critical only proves that the All Seeing Eye has ruined our sense of childlike wonder. Why settle for the false nostalgia of billion-dollar retreads of old cartoons and toy lines when you can have the real thing?*

Besides, it's not all bad. The effect of the Sultan riding a horse across the sky still looks pretty good, and one can't help but be awed by the massive, colorful sets and the beautiful matte painting backdrops. This wasn't some cheap production, but an ambitious Technicolor undertaking. The new Criterion transfer of the picture shows every beautiful detail, restoring the bright hues and cleaning up each and every frame. There was probably a time in the past when no one thought movies this old would ever look this good again, but as with so much in The Thief of Bagdad, seeing is believing.

In addition to the new transfer, the Criterion Thief of Bagdad comes with two audio commentaries and a second disc entirely of extras. Of those, a half-hour program about the visual effects featuring special-effects legend Ray Harryhausen unravels the tricks the filmmakers used to create the magic in the movie, including pioneering the bluescreen process (there is a separate demonstration of how bluescreen works) and the employment of miniatures and perspective shots. There is a lot of great footage and photos from the set, though Harryhausen, even as he discusses the techniques, makes a good point about the destruction of illusion in our current need-to-know society. I have long felt that the one downside of the DVD age is that everything is explained to us, we always want to know how it's done rather than marveling at what was done. So, kudos to Mr. Harryhausen.

Alongside this documentary is a feature-length propaganda film from 1940, The Lion Has Wings, which couldn't be further from Thief of Bagdad in tone and subject. This was produced by Alexander Korda and made during a hiatus on Thief of Bagdad. It was partially directed by Michael Powell, and stars Ralph Richardson, Merle Oberon, and June Duprez--though roughly 2/3 of the movie is documentary footage. Even propaganda from the good guys is still propaganda, and so most of The Lion Has Wings comes off as stiffly preachy. The ever-present narration never lets us forget we're supposed to be learning something. The first twenty minutes is a rundown of the build-up to war and what England stands to lose if Hitler were to have his way, and then the rest of the movie is spent with the Royal Air Force. Real combat footage is interwoven with images of the homefront and a dramatization of the flight and ground crew's experience during bombing raids.

It's an interesting curiosity, but not much more than that, and certainly a comedown after The Thief of Bagdad.

* I should note, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull manages to get the nostalgia thing right, and if you're eager to go see it this weekend, I'd recommend following it up with the Thief of Bagdad when it comes out on Tuesday. It will make for a good chaser to quench your swashbuckling thirst.

No comments:

Post a Comment