No one likes jury duty. Well, some people probably do, but one hopes they are smart enough to keep it to themselves. At the same time, the right to a trial by jury is a great thing about the American justice system, and everyone should serve at least once and see how it all works. If you've ever been stuck in a back room arguing over the particulars of a case, you will never again wonder about some of the baffling verdicts passed down by civilian tribunals in high-profile trials. It's harder to armchair deliberate when you know how sentencing instructions and the literal wording of the law can affect the outcome of a seemingly open-and-shut debate.

While juries I have served on have never been as articulate, or as heated, as the regular joes and uncommon men who populate the tiny room of 12 Angry Men, Reginald Rose's script captures the back-and-forth quibbling over legal minutia pretty well. Inspired by his own time on a jury, Rose first wrote 12 Angry Men as a teleplay broadcast live in 1955 (which is also included here), and then expanded the hour-long program into a full movie screenplay, which was directed by Sidney Lumet in 1957.

The movie begins after the trial is over. Outside of some short instructions from the judge and a lone shot of the accused, we have missed the proceedings. The camera travels the jury box, recording the faces of the jurors, before following them into a cramped room where they will be asked to stay until they can agree on a verdict. Most assume that the deliberation will be quick: the first vote is actually eleven for "guilty." The lone hold-out is Juror #8 (Henry Fonda), whose mind isn't made up. Maybe the boy killed his father, maybe he didn't. Despite pressure from the others to bend, #8 stays true to his insistence that if they are going to send a 19-year-old kid to the electric chair, they should at least spend some time exploring the realms of reasonable doubt.

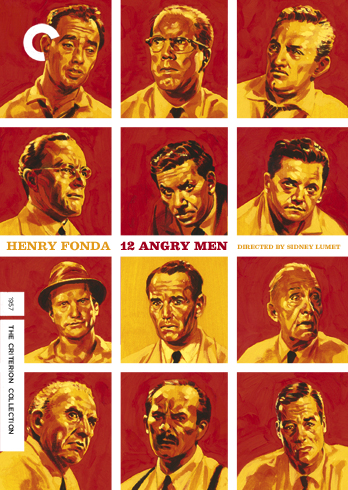

Slowly, #8 works his way through the case. The testimony of the downstairs neighbor is questioned, then the uniqueness of the murder weapon, a switchblade knife. One by one, each juror is drawn into the discussion, and one by one they reveal something about who they are. #9 (Joseph Sweeney) is an observant old man, #5 (Jack Klugman) is from the same slums as the accused, and #11 (George Voskovic) is an immigrant who believes in America's sense of justice. On the stubborn side we have #3 (Lee J. Cobb), the father with an angry temper, and #4 (E.G. Marshall), the business man with the steady demeanor. There is also #7 (Jack Warden), who just wants to get out of there and go to a ballgame. And perhaps worst of all, the one that everyone else eventually turns against, is #10 (Ed Begley), a racist who believes the boy, who looked like he was maybe Puerto Rican, is a natural born liar, it's a byproduct of his skin color.

As the case disintegrates, personal feelings flare up, sides are taken, and threats are made. Rose has built a microcosm of American society, and also a sounding board for political ideas that were prudent to the American experience of the time. Civil rights, the vilification of unpopular or "radical" ideas, economic divides, the notion of might making right--these concepts are challenged just as the evidence is challenged. What would motivate a witness to lie? How much does an abused kid's background matter? What does it mean to be impartial and what constitutes reasonable doubt? For a locked room scenario, it's a surprisingly potent drama. Each man is given a rich background and each has an inner life. Nothing here is incidental. The writing is precise and dramatic and it's not afraid to be writing.

For his part, Sidney Lumet, who was transitioning out of television into this, his first feature film, keeps 12 Angry Men moving. Boris Kaufman's camera is agile and lively, moving through the room, capturing important expressions and gestures. The director and his cinematographer enact bold compositions, emphasizing the cramped space via contrasts of physical size. One man foregrounded may tower over the one in the background, but the power is often shifted: what the "smaller" man says weakens the "bigger" man. Live television had taught Lumet how to use a limited set to his advantage. If you think about it, it took TV to bridge the gap between stage and film, not just by putting together complicated one-time performances, but also by teaching a generation of new filmmakers to be economical and use confined spaces to their advantage. While the 1960s might have kicked down the walls of cinema and explored the open frontiers that new technologies allowed for, directors like Sidney Lumet and John Frankenheimer and others who first worked in l950s TV used restrictions to their advantage.

12 Angry Men had a profound effect on legal procedurals to follow. The notion that a criminal trial could be the basis for exploring bigger ideas has been exploited in most recent memory by the legal dramas of David E. Kelley and the whole Law and Order franchise. Even if those shows did move the action back into the courtroom, they still owe something to what Reginald Rose and Sidney Lumet (and Frank Schaffner, who directed the 1955 broadcast) did here. The whole strata of society passes through the doors of any given justice building, and for true justice to hold sway, they all must be honored the same.

Frank Schaffner's original 1955 broadcast version is thankfully included on this release, giving viewers a chance to witness the historic, Emmy-winning Studio One production. In some ways, this older version is somewhat superior. For one, the cast is not as well known, and having Robert Cummings (Hitchcock's Saboteur [review]) as Juror #8 instead of Henry Fonda makes the character more interesting. Fonda brings with him a certain moral authority, whereas Cummings' stuttering, unsure portrayal makes him less immediately convincing. Likewise, not showing the accused leaves that character up to our imagination, and a picture of him forms the more we learn. Lumet chose a scrawny, sympathetic looking kid that we make up our mind about right away. In general, the drama is more concise here. Having less time meant that Reginald Rose didn't have the opportunity to go off on as many personal tangents for each character, and one could argue that makes the dramaturgy less heavy handed. Both work for me, and I think in the spirit of this thing, we could make a case for either/or. (A 15-minute introduction by Ron Simon, from the Paley Centre for Media, adds further context.)

Most exciting, as well, is the addition of another live television drama, this one pairing Reginald Rose with Sidney Lumet a year before 12 Angry Men. The teleplay Tragedy in a Temporary Town features another mob of men, but this one isn't brought together by the legal system. Rather, it's vigilantism. The show stars Lloyd Bridges and two men that would go on to work for Lumet in 12 Angry Men, Jack Warden and Edward Binns (Juror #6). Set in a worker's camp, the story revolves around a young girl getting grabbed and kissed in the darkness. Failing to listen to Bridges' protest, Warden forms a posse to hunt through the camp, dragging the traumatized girl around in hopes she'll find her attacker. They barge into every home, writing down the names of any male age fifteen and over, until they land on a suspect that they can accept. It's not about finding the right guy, but about venting their restless anger.

Rose touches on the idea of personal "justice" in 12 Angry Men. The workers here are like the jurors unleashed. If the men in the other film could have gotten out of the room and been allowed to do as they wished with the accused, they very well could have resorted to violence. Here the misguided actions of the lynch mob threatens the safety of the whole community rather than making it more secure. Ironically, the men in the posse are looking for a threat within, not realizing they are it. Bridges is forceful in the lead, though his moral equivocations don't quite match Warden's menacing bluster.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVD Talk.

Please Note: The images used here are from promotional materials and are not taken from the Blu-ray edition under review.

No comments:

Post a Comment