At this time of year, when we're meant to reflect on what we have and the state of our world, those in need of a reality check need go no further than Hunger, artist Steve McQueen's 2008 portrait of Irish Republican Army activist Bobby Sands. This cinematic tribute to true political sacrifice is a sobering reminder that much of what is fair and just in this world has been purchased at extreme personal cost by people who have had the guts to go farther than anyone else would. It's easy, for instance, to scoff at the Occupy Wall Street protesters and quibble over the occasional missteps the movement as a whole has suffered, but ask yourself, why aren't you one of the ones to uproot your life to make a stand? Is there anything you believe in enough to put your livelihood, or even your very life, in jeopardy?

Michael Fassbender (Fish Tank [review], A Dangerous Method [review]) stars as Sands, an IRA leader who was sent to a brutal state-run prison for his alleged crimes in the fight for a unified Ireland. Once inside, Sands was part of an ongoing action to convince the British government to recognize the IRA soldiers as political prisoners and not as average criminals. At the start of Hunger, it's 1981, and the imprisoned have been carrying on a "blanket" protest since the mid 1970s. Essentially, the jailers expected the prisoners to wear a uniform, while the prisoners demanded to wear their own clothes to differentiate them between the non-political inmates. With no other options, they went naked except for the blankets from their beds. This later morphed into a "no wash" protest, which is basically what it sounds like, though as McQueen shows in disgusting detail, this also involved letting food rot in the corner of your cell, painting the walls with your own feces, and dumping your urine into the corridors for the guards to walk in.

As we see, Sands and his fellow protestors were routinely beaten and bathed. Their hair and beards were cut off with large scissors with little regard for their personal well-being. Eventually, "negotiations" broke down when the compromise to let them wear pre-determined "civilian clothes" led to brightly colored golf outfits. Seeing that this was getting them nowhere and that attention was shifting to other aspects of the struggle, Sands reinstituted a hunger strike. A previous starvation protest had failed due to poor planning, but this time he had created a staggered system where more men would join the action periodically. He was to lead the way.

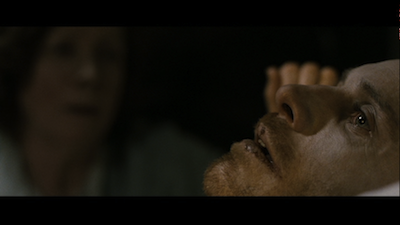

The final third of Hunger is Bobby Sands' slow death from lack of sustenance. Steve McQueen re-creates his deterioration with exacting, excruciating effect. Michael Fassbender reportedly went on a monitored diet to allow himself to lose enough weight to show Sands at his most emaciated, though simple weight loss is not the full extent of what Sands went through. As a doctor details to his parents, starving to death means losing all function as your body literally falls apart. Sands' skin was covered in festering bed sores, and his agitation reached such a state that the bed sheets couldn't even touch his fragile flesh. It took him 66 days to die.

McQueen, who co-wrote Hunger with playwright Enda Walsh (Disco Pigs), chooses not to frame Sands' final days as some kind of triumphant finger in the eye of "The Man." Rather, he assembles the narrative almost like a short story collection, stringing together various scenes and anecdotes to create an impression of the prison experience for Sands and his comrades. A good fifteen or twenty minutes passes before we even see Bobby Sands. Instead, we are first introduced to a cruel guard (Stuart Graham) who regularly brutalizes the IRA boys, and then a new arrival at the jail, a fighter named Davey Gillen (Brian Gilligan). This gives the viewer the impression of a unified effort where all participants are equal. Sands' importance in the protest only emerges slowly, we're halfway in before he takes over the movie in full.

This shift comes with one of Hunger's most stunning scenes, a sitdown between Sands and the priest Dominic Moran (Liam Cunningham). Shot as one unbroken sixteen-minute conversation, Sands lays out his plan for the strike as he and Father Moran debate what the true righteous path would be. It's a stunning piece of acting from both men, who maintain a natural flow in their dialogue, swapping humor for anger with a turn of phrase, never once breaking from the moment. Indeed, this is where we learn the sense of dedication ingrained in Sands' personality. As a youth, he was a cross country runner. He can endure pain in the long haul.

Rather than show off their command of the camera, McQueen and director of photography Sean Bobbitt (he also shot Michael Winterbottom's Wonderland), let the virtuoso performances dominate this important moment. The camera doesn't move, it stays fixed on the two sitting men and the table between them. There are plenty of other moments where the pair can show off their visual panache, be it the painterly use of the shit-covered walls, using the patterns as symbolic backgrounds, or the horrific bursts of violence when the inmates are pulled from their cells for all manner of degradation. They let these play, too, never cutting a moment short when the longer study will produce a stronger impact. Some might find some of the scenarios a little on the nose in terms of visual imagery--the fate of the Graham's guard, for instance, looks like the study of a macabre statue--but these things are deliberate on McQueen's part. He has a limited space in which to extract some beauty from the ugliness that permeates the situation.

In some ways, Hunger's landscape only contracts as the film progresses. The final scenes of Bobby Sands confined to bed, in particular, are understandably reduced to a single space. As her starves himself, the incarcerated man also becomes imprisoned in his own body. Ironically, here Sands can finally bust out, and so too does the camera. McQueen takes us out of the prison, away from the city, and into the wilderness, also taking us back in time to the formative experience of Sands as a young runner. These final scenes are reminiscent of Julian Schnabel's The Diving Bell and the Butterfly [review] in how McQueen masterfully juxtaposes how one's body can be immobilized but the mind will never be restrained.

Because of this, the solemn coda that ends Hunger can be seen as a positive. We are to regard the reforms that followed as a validation of Bobby Sands' sacrifice. The will of a single individual can start a chain of events, binding him with other likeminded individuals, and ultimately enacting true change. It just takes the one to start for the many to follow suit.

Merry Christmas.

No comments:

Post a Comment