The early 1980s was a weird time in my movie-going education. My family did not go to movies for most of my early childhood, a religious embargo I managed to break in 1979 when a seven-year-old me whined his way into getting to see The Black Stallion

As a matter of fact, Mom, I was.

Anyway, once this barrier had been shattered, all bets were off, and we went to the movies pretty much every week. My father was a master theatre hopper, and so an outing to the movies usually involved seeing two or three movies in a day, sometimes all of us going to completely different films. I chronicled some of this in my review of Hopscotch, one of those movies we saw that I probably shouldn't have seen at my age. It makes for a strange variety of nostalgia, these formative years where I could see Kurt Russell in both a revival run of The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes

Anyway..., of movies that I saw but maybe shouldn't have, I think they could be classified in three categories. First were the movies like Silkwood that I liked but probably didn't really understand why. Second were the movies that I knew were terrible and even kind of offensive, such as De Palma's Scarface

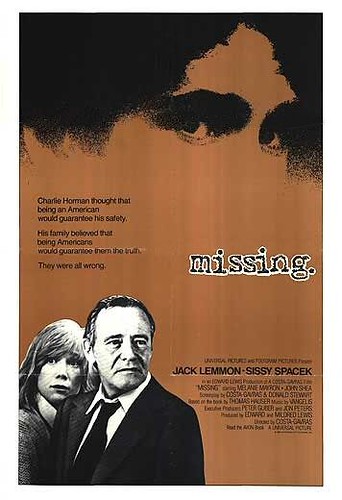

One of these third beasts was Costa-Gavras's 1982 political drama Missing. I was ten when it was released, not yet ready to absorb the entirety of what this extremely complex docudrama had to say. I've always remembered seeing it, though, and I even remember being bored while we were watching it, maybe even walking out or going to sleep. Yet, just remembering that must hold some significance. This thing I could not understand had obviously left an impression. Why else would I, twenty-six years later, still remember the grainy black-and-white newspaper reproductions of the movie poster from when we were going through the listings to see what was playing? How else do you explain that I had three images from the movie lodged in my brain? Jack Lemmon holding Sissy Spacek close, helicopters, and John Shea posing for a photo by the beach--all three of these would come to mind any time the subject of Missing would come up.

I admit to feeling a little electrical charge when I first saw the announcement that Criterion was releasing Missing. After all this time, I would sit down with this highly lauded film and relive the experience that had so baffled me as a ten-year-old boy. It's impossible to explain why I had waited all this time to see it again. Things just have a habit of staying out in front of you, y'know?

I'm pleased to say up front that my mind was effectively blown. Missing is a phenomenal motion picture, on par with iconic intelligent thrillers from the 1970s like All the President's Men

Good journalistic storytellers know that there is an inherent drama in real life that is just as reliant on coincidence and narrative convention as anything invented from whole cloth. The screenplay for Missing was written by Costa-Gavras, Donald Stewart, and John Nichols, working from a book by Thomas Hauser, and the writers smartly see that the drive of their two very different characters makes the personal journey they undertake in searching for Charles just as fascinating as the investigation itself.

Charlie and Beth were young idealists living in Chile for no other reason than they enjoyed the way of life down there. Though left-leaning in their politics, neither were political activists. Charlie only really became caught up in what was happening in Chile because he happened to be there, either the right place at the right time or the wrong place at the wrong time, depending. As soon as Ed Horman arrives in Chile a couple of weeks after Charlie has disappeared, it's obvious that father and son couldn't be more different, even without them ever having a scene together. Ed is a devout Christian Scientist who believes in God and country and doesn't understand why his son would live in South America, living as if he were poor and not continuing on the life path his family always thought he was meant to follow. Ed doesn't believe Beth's theories about Charlie's abduction, he's more inclined to trust his government and even accepts the explanation that maybe this is a stunt Charlie is trying to pull in order to embarrass the U.S.

As a Christian Scientist, however, Ed has one core belief that eventually puts him and Beth on the same page. When he is asked to explain the fundamentals of his religion, Ed boils it down to having faith in the truth. The common goal of both father and wife is to find out what happened to their son and husband, and the further they go into the investigation, the more their beliefs merge.

From an acting point of view, Lemmon has the meatier role. His character is the one who is going to change the most, who is going to have the foundations of his beliefs rocked. It's probably no coincidence that he confirms his change immediately following an earthquake, the shaking hotel reminding him enough of his own mortality and dislodging his stubborness to such a degree that he feels he has to apologize to Beth. It's not a showy transformation, though, it's one that happens little by little. Lemmon already had a natural hunch at this time, but as Ed grows increasingly defeatist, it becomes more pronounced. The actor mainly plays him as soft-spoken when dealing with authority, but more tenacious when talking to Beth. It's the tenacity of a father, however, and when he realizes that his attentions are misplaced, we see the mannerisms reverse. Ed becomes a verbal attack dog when stonewalled by the U.S. embassy in Santiago.

Ed's transformation is not just in how he views the world, though. There is a far more subtle shift in the writing. He also changes as a father. Just as he is at first angry with Beth, he is also angry with his son, not understanding how his little boy became a man so far from the family's way of things. In trying to figure out what happened to Charlie, Ed starts to see how his parenting has really influenced his child. More than once someone points out a gesture that the two share, or how they each behaved in a similar situation, and each time it closes the gap. The father discovers that the fruit stayed much closer to the tree than he had ever thought, and the same tenacity for the truth that has brought Ed searching for his lost child is also why the powers that be wanted the child lost in the first place.

Missing proved to be a real political hot potato at the time of its release. Though the film gets no closer to the answers than Ed and Beth did in 1973, it does lay out a complex map of events that don't seem so far fetched now that we know more about the Pinochet government and the U.S. connections to the same. I don't think it would be a stretch at all to draw analogies between what Nixon and his people may have done down in Chile back then and what the current administration has also pursued in its involvement in regime change in the Middle East. More importantly, though, I think Missing rather sharply defends a particular strain of patriotism that current political rhetoric would have us believe is somehow un-American. From where I sit, both Charles and Ed Horman are the best kinds of patriots, the ones who love their country enough to call it out on its shame not to detract from but in order to defend it principles. When Ed tells the people who have filibustered him that he is going to take every action to make sure the word gets out about what they have done, one of the U.S. consuls says to him, "Well, I guess that's your privilege." In response, the movie version of Ed memorably declares, "No, that's my right! I just thank God we live in a country where we can still put people like you in jail." Inherent in that statement is the core belief that United States, regardless of the wrong turns it may take, is a nation that is always better than the bad decisions of the most misguided or selfish of its people.

Of course, sitting in a theatre at age ten, I wondered more about when Missing would be over than I pondered what Costa-Gavras was telling me. (The director has himself said that Missing stands as a testimonial of the power of free speech in America, and is also swayed by the individual's personal beliefs or investment in seeing justice done.) Even so, whether or not I was conscious of it, I think the message still got through, at least enough to leave me with the impression that eventually revisiting the movie would be important. That's the true power of a piece like this, and the true validation of Ed Horman's faith: the truth will always get through, regardless of how many shadowy hands try to hold it back, as long as the rest of us demand it be told.

Costa-Gavras

1 comment:

Really excellent review. Thank-you.

Post a Comment