Maurice Faugel (Serge Reggiani) only recently finished serving a four-year prison sentence. Since his release, he's been told repeatedly that he's not the man he was when he went inside. Observers apparently think he's lost some of his nerve. Maurice seems to accept this to a degree, but his motives for doing so--like everything in Le doulos--aren't exactly clear. Given that the first person we hear telling Maurice this, the middle-man fence Gilbert Varnove (Rene Lefevre), ends up on the wrong side of his gun--a gun Gilbert actually loaned to Maurice--one could assume the hood is going along with this lowered estimation in order to use it to his advantage. Given the hard times that are to follow, it's also possible everyone else is right, and Maurice is merely staying one step ahead of the reaper looking for that last big score.

Le doulos is a 1962 crime picture written and directed by hardboiled French master Jean-Pierre Melville. As we're informed at the beginning of the film, the phrase "le doulos" refers to a kind of hat. Specifically, it's a hat that is worn by a police informer, and so "doulos" has become slang for a stool pigeon. (An alternate title for the movie has been The Finger Man.) Though not as sturdy and high-minded as one of Melville's Eastern philosophy crime dramas (Le samourai, Le cercle rouge), Le doulos is a curvy double-cross caper that twists its tough-guy tropes into a yummy movie pretzel.

In a way, you could say that Maurice is the source of his own woes, as the chain reaction of screw-jobs begins when he shoots the unsuspecting Gilbert in cold blood. Our boy will later find out that he had good cause to take the crook out, as the good will Gilbert has been showing him since Maurice got out of prison might be payback for a bad turn Gilbert did him way back when, but at the time of the robbery, Maurice doesn't know that. He's quite literally annihilating the hand that's been feeding him, making off with a pile of hot jewels and $20,000 in cash, all of which he promptly hides for later. As it turns out, he's setting up another score for the following day where he and his buddy Remy (Philippe Nahon) are going to knock over the house of a rich couple who are on vacation. He's had his girlfriend Therese (Monique Hennessy) staking out the joint, and his friend Silien (Jean-Paul Belmondo) is loaning him the safe-cracking equipment. He's keeping mum to both Silien and their friend Jean (Philippe March) about the location of the heist, however, because he wants to take the fall on his own if something should go wrong.

He's also not sure if he can trust those guys. Therese doesn't care for Silien, but Silien thinks Jean might have a big mouth. Maurice tries to adopt an innocent-until-shown-otherwise attitude, but he can't escape that someone sold him out when the cops show up to foil the crime, leaving both Remy and the chief inspector dead and a bullet in Maurice's shoulder. He's pretty sure Silien is his man, and the cops, led by Captain Clain (Jean Deailly), are pretty well convinced of the same. They know where the robbery was, but the dead cop didn't tell anyone else who was supposed to be involved. They believe the surviving thief is a cop killer, and they want Silien to tell them who it was.

What follows is an ingenious cat and mouse game, though even more between Melville and his audience than between his characters. Silien sets up some elaborate plans that only he knows, and dead bodies are starting to show up without anyone claiming the kills. I don't know if Pierre Lesou's original novel was written to confound its audience the way the movie does, but Melville is extremely selective about what he shows us in Le doulos. Faces are regularly hidden in shadow and figures filmed only from behind so as to leave us constantly unsure of who we are seeing do what. For instance, Maurice only tells one person about his hidden stash of cash and jewels, but Melville doesn't reveal the identity of who goes to the secret spot to dig it up right away, choosing instead to tease us a little. His camera cleverly encourages us to "follow the hat," which would make us think that we know who is responsible, but with this many crossings and double-crossings, the truth gets obscured rather quickly. Melville is famous for his silences, and so much remains unsaid in Le doulos. The only person who regularly articulates what he is thinking is Maurice, and in a way he is our point-of-view character. Accepting that, it's logical storytelling that even when the camera leaves him to follow others, we are only made privy to the surface

motivations. All we can know is what we see, and even that is limited.

By the denouement, when all the pieces are laid out, I doubt anyone but the actual cartographers would be able to read the map, which is just as it should be. When you think of classic pictures of this type, from Hawks' Chandler adaptation The Big Sleep

From a performance standpoint, Serge Reggiani is both weaselly and fatigued, the by-then-veteran actor showing a lot of insight regarding what it means to be an older man playing a younger man's game. He was returning from movie jail himself (something discussed in the supplemental features), and perhaps he also sensed the Belmondo was about to steal the show, and he channeled some of that anxiety into the role. Belmondo plays the a gangster who is more on the ball, but with the youthful confidence that also made him so good two years prior in Classe tous risques. Unlike, say, his Breathless performance, where his tough-guy act is meant to be an act and is clear as such, Belmondo's portrayal of Silien walks a more perilous tightrope. For all the dastardly deeds he performs and as much as we see Silien as the bad guy, Belmondo manages to keep his natural charisma from being buried. We might recoil at his actions, but we can never quite hate the lug. His seductive eyes, his way with a smirk--he's the bad boy we love to hate and hate to love.

Which fits the tenor of Le doulos perfectly. As viewers, we never know which line to follow, but something in our make-up compels us to peer into the darkness. Melville provides us with plenty of murky shadows, and the more lurid the secrets inside them, the more he draws us in.

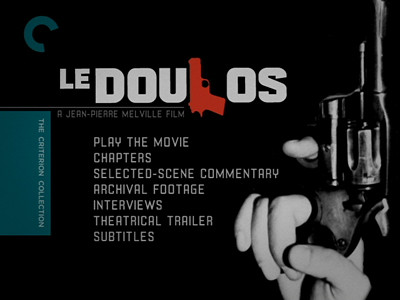

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

No comments:

Post a Comment