The 1962 black-and-white horror feature Carnival of Souls is a ghost story of a classic variety. It's the kind of mounting chiller that comes from the oral tradition, begging to be told around a campfire or with a flashlight tucked under your chin. That it was made by a group of guys using equipment from the industrial film company they worked for in Lawrence, Kansas, probably only adds to that homegrown urban legend feel. Like the best of these kinds of stories, it is steeped in convention, yet its telling is so involving, one forgets what one knows about such tales and is swept away by fright.

Carnival of Souls begins unassumingly on a small town road where a car of guys challenges a car full of three girls to a drag race. On a rickety old bridge too narrow to hold both vehicles, the ladies careen over the side, sinking into a sandy river. Hours later, the police and rescue teams can't find the car, but one of the ladies inexplicably appears on a muddy jetty, soaked to the bone but otherwise unharmed.

Mary Henry, played by otherwise unknown actress Candace Hilligoss, is an organ player who had been scheduled to leave Kansas for Utah two days later. A position tickling the pipes at a church awaits her, and she sees no reason to call off her plans because her two friends have died. Mary is a bit of a cold fish, which is maybe how she survived the icy river. Or maybe she took a knock on the noggin and that's why she's suddenly so moody. One minute she wants to be completely left alone, the next she is cheery and wants to chat and hang out.

Driving alone at night, Mary heads for her new home, but once she crosses over into Utah, strange things start to happen. The image of a ghoulish man appears in the passenger window, seemingly defying all laws of physics. As soon as she shakes off this hallucination, he appears again, this time standing in the road in front of her. She swerves to miss him, driving into a ditch, a dangerous mirror of her previous auto accident, but when she looks back to the road, the man is gone.

Along the same road, Mary sees a strange building off in the distance. A gas station attendant informs her that it's an abandoned carnival pavilion, and it's been boarded up for years. Mary feels a strange attraction to the pavilion, and she even tries to go inside it the next day when out on a drive with her new boss, the church minister (Art Ellison). He won't let her go inside, though, because it's against the law. Mary says she will have to return another time then, and the viewer has a sinking feeling that she will. The preacher's admonition was intended to enforce the laws of man, but the implication could be that this place violates the laws of God, as well.

The narrative of Carnival of Souls is exclusively the tale of Mary trying to figure out what is happening to her. The latter day spook in the tailored suit she saw on the road keeps following her, appearing in her boarding house and even in the church, always moving toward her like he wants to tell her something. The increasingly nervous Mary also starts to have other hallucinations where the world goes quiet. She can see everyone else, but they can't see her; she can hear herself speak and her footsteps on the ground, but she can't hear anyone else talk. She even goes into a trance while playing the organ, seeing the zombified man and a host of other specters rising from the inky river near the carnival pavilion, where they engage in a ghostly ball. This scene, like the bulk of Carnival of Souls, is set to the morose organ music composed by Gene Moore. It's a smart stylistic choice, invoking cultural memories of carnivals, religion, and gothic tales of the macabre. It also has a psychological oppressiveness that ties into the fact that Mary is an organist herself. It seems to rise out of Mary's own psyche, an inescapable expression of her fear.

Candace Hilligoss is the secret weapon of Carnival of Souls. Without her, the movie wouldn't work. A lanky blonde, she looks like a prototype for Anne Heche. She is very good at conveying confusion and panic. Unable to figure out what is happening to her, she turns to a variety of people--the minister, the creepy neighbor in her boarding house (Sidney Berger), the local doctor (Stan Levitt)--all of whom don't take her plight very seriously. They are the kind of annoying people who think sadness can be cured by a stranger telling you to smile. They all think she just needs to socialize more, though how they express this opinion is more telling than Mary realizes. Catching her playing a manic dervish on the church organ, the priest accuses her of having no soul. So, too, does Mary's would-be suitor decide Mary is frigid and accuse her of being an arctic tease. These all foreshadow the final reveal, when we finally learn Mary's true fate, when her pursuer can deliver his good news.

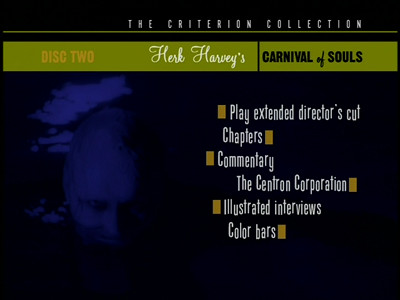

Mary's spectral stalker is an iconic horror figure. Simple white make-up, a black suit and tie, and a wide-eyed look are all the silent fiend really needs to give viewers the creeps. Played by the director and producer, Herk Harvey, he is the simplest of villains, doing very little but sparking the audience's imagination. As in the best scary movies, what we think might happen is just as integral to the mood of fear as what actually does happen. In the Criterion booklet with the DVD, screenwriter John Clifford says he wrote the screenplay sequentially, never knowing where it was going until he got there. The only real trick he had up his sleeve was making sure that Mary stayed totally alone, that no one believed her or helped her in any great way.

Clifford's writing process is indicative of the production as a whole, with a crew of people who had never done this kind of thing before just grabbing some cameras and going and doing it. Carnival of Souls was shot in three weeks for $30,000, and though some of the acting and the storytelling can be a little clumsy, the modesty of the endeavor never really shows. This is down to the masterful photography of Maurice Prather than anything else, even more than Gene Moore's music or Herk Harvey's dark-eyed bad guy. Prather's eerie black-and-white compositions have a chilly beauty. He begins with the opening credits, composing a naturalistic mis-en-scene featuring the deadly river that swallowed Mary and her car, showing us a world that is real and familiar. This makes us accept what we are seeing so that we will go on accepting it even as the movie takes a turn into the dark and sinister. Using the abandoned Saltair amusement park on the Great Salt Lake was a stroke of genius, and Prather's industrial work clearly prepared him to capture its worn-down surfaces and shadows.

This low-budget exercise in mood doesn't really have any jump-out-of-your-seat shocks, but that's okay, it's more about taking you deeper into its heroine's dreadful dilemma. I actually found it more involving watching it this time than I did when I first got this DVD a couple of years ago. While we would expect more contemporary indie horror films to go for the splatter (think Cleaver, the movie Christopher made in The Sopranos), Carnival of Souls reaches back to more classic scarefests, the kind that uses less to frighten us more.

By the by, the cheeky references to Mormonism and the almost missionary-like doggedness of the mysterious man's pursuit of Mary was intentional, but I don't think the filmmakers intended any connection, so I don't think it deserves a greater focus than I've given it. I fully admit it's kind of a cheap joke, based solely on the fact that the film is set in Utah. Though no denomination is given, the minister whom Mary works for is wearing a priest's collar, which I don't believe is the uniform of the leaders of the LDS church, and he in no uncertain terms is imploring Mary to accept his version of heaven. Logically, this would mean the alternative is hell, but given how other Christian denominations view the Mormon faith, I could definitely see someone trying to bend Carnival of Souls into some kind of propaganda. "Come to the right church, Mary!" Personally, I'm all for personal choice, and whatever you choose, hey, that's fine with me. No offense is intended, it's just something that popped into my head while viewing the picture.

No comments:

Post a Comment