Of all of man's fears, there is perhaps no greater than the fear of death and what comes after. While some humans fear that there is nothing on the other side, the greater dread is that there is more after this life, both a paradise and a wasteland, and despite our best efforts, we might end up in the wasteland. Even those who believe there is nothing awaiting them must have the occasional nagging worry that they are wrong and by choosing wrong, will be doomed to eternal punishment.

Many artists have tried to visualize what Hell would be like. The paniters Hieronymus Bosch and Francis Bacon are probably two of the most well-known and highly regarded, and I could see their influence in Nobuo Nakagawa's 1960 film Jigoku (Hell). I also could see touches of classical images from Japanese folklore, the odd stylings of their ghost tales and even the traditional garb of feudal lords. Enma, the King of Hell (Kanjuro Arashi) looks like an old shogun filtered through kabuki theatre and the worst drunken Halloween you've ever had.

Jigoku is a B-movie morality play, ripe with melodrama but short on histrionics. That latter qualifier is not necessarily a good thing. There is a little too much Asian reserve in the first half of the movie, which is meant to set up the colorful lives of Nakagawa's sinners so that by the movie's final act, when they have all died and gone to Hell, Enma will have something to punish. The screenplay, co-written by Nakagawa and Ichiro Miyagawa, borrows all of its scenarios straight out of soap operas, but it's staged like the most serious of social dramas.

The protagonist of the movie is university student Shiro Shimizu (Shigeru Amachi), a studious young man engaged to his professor's daughter, Yukiko (Utako Mitsuya). Shiro's life is full of temptation, some of which he's indulged in on his own (he and Yukiko have been sleeping together), and some of which he is egged into by his friend Tamura (Yoichi Numata). Tamura is a strange character, seemingly supernatural in his ability to appear out of nowhere and his limitless knowledge of other people's foibles. He knows about Shiro's sex life, and he not only knows about the war crimes of Yukio's father (Tarahiko Nakamura), he has photographic proof that shouldn't even exist. A devilish dandy who regularly arrives carrying a rose, Tamura has taken it upon himself to remind everyone that, even if he has no moral compass, the world does.

On a night out, Tamura and Shiro accidentally run down a drunken gangster (Hiroshi Izumida) in their car and leave him to die. Shiro is haunted by the deed, while Tamura is haunted by the fear that his weak-willed friend will rat them out. The gangster's mother (Kiyoko Tsuji) and girlfriend (Akiko Ono) swear revenge, but poetic justice catches Shiro first. A taxi ride with Yukiko ends with the car wrecked and the driver and Yukiko both dead--and just before Yukiko can confess to Shiro that she's pregnant. (Kind of a spoiler, I suppose, but I can't imagine anyone in the audience today not realizing what she's about to say when she is cut off.)

The two car crashes are the first of many doubles Nakagawa plays with in Jigoku, a reflection of the two plains of existence his story traverses, which is further reflected as the relationship between the audience and its cinema. The most significant of these pairs emerges when we are introduced to Sachiko, the girl Shiro meets when he returns home to visit his ailing mother (Kimie Tokudaji) and philanderer father (Hiroshi Hayashi). Sachiko, also played by Utako Mitsuya, is a doppelganger of Yukiko, which naturally does the boy's head in. He's also tempted by the dueling mistresses trying to lure him away from his heart's desire. Kinuko (Akiko Yamashita) has been bedding Shiro's father, but now she wants the son to take her to Tokyo, while Yoko, the former moll of the dead gangster, has come searching for Shiro at his hometown retreat. She carries a red umbrella, which contrasts to the pink umbrella used by both Yukiko and Sachiko--one is fiery and passionate, the other softer, more love than sex. (Yoko's lily is also a dark omen and contrasts with Tamura's rose.) Nakagawa even doubles-up on the cuckolding. Shiro's father is cheating with Kinuko as well as on her, but she is trying to cheat on him with his son, while it turns out that Shiro's mother was stolen by his father from the alcoholic painter Ensai (Jun Otomo), who is Sachiko's father. You almost need a flowchart to keep it all straight.

These sinners finally converge on a night of partying following the death of Shiro's mother. In another doubling, Shiro's father and the corrupt townspeople get drunk in one room while the residents of the old folks home he is caretaker for party in another. Both are inadvertently poisoned by two separate sources--the old people from the sustenance Shiro's father is meant to provide, the others as a result of their own debauchery and Shiro's sins. This massive group death thus pulls all of these souls down to Hell at the same time, where Nakagawa can visit their sins back upon them and we can finally start to get into the rancid meat of the movie.

Hell in Jigoku is a nightmarish landscape, many of the special effects Nakagawa employs predicting the psychedelic aesthetic that would emerge later in the decade. At the start of the film, Yukiko's father is lecturing on the different versions of Hell that exist in the world's religions, but the focus is on the Buddhist variety and I would guess that Nakagawa draws a lot from that here. There is some fire and brimstone, but there is even more fetid water and obscuring smoke. It's like a dream that you can't get out of, where the farther you travel the less distance you actually traverse. There is nowhere to go, but the compulsion to find an escape is irresistible.

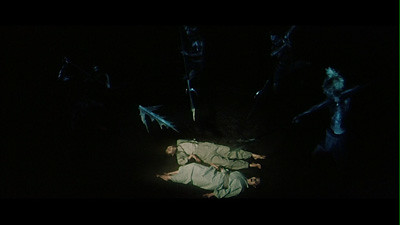

The various characters from the set-up are beset upon by demons and are delivered befitting punishments. The corrupt police officer (Hiroshi Shinguji) is placed in handcuffs so tight, they sever his hands at the wrist, while the one-eyed journalist (Koichi Miya), whose ocular infirmity was already a symbol of his inability to clearly see the truth, has his other eye gouged out. Tamura, who even in Hell is still picking at Shiro, is picked at himself, repeatedly stabbed by a demon's pitchfork. Immediately upon the completion of these tortures, the victims' bodies are restored (Kakagawa uses primitive jump cuts to go back and froth between each state) and it starts all over.

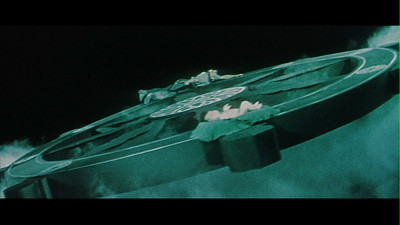

Nobuo Nakagawa really goes for it in these final scenes, and while the results aren't exactly terrifying, the inferno he creates is impressive in its ambition. In the earthly scenes, the director had already employed extreme angles--shooting from below and above and from voyeuristic vantage points; inverting the image at morally crucial moments to suggest that any sense of up or down, right or wrong, has been lost--but he takes it to the extreme once he takes us to the underworld. Anything goes at this point. There are distorted colors, irises that warp the pictures like funhouse mirrors, burning lakes of blood and boiling cauldrons, a swinging pendulum blade, mountainous eruptions, spinning wheels, throngs of sinners driven mad with panic, demons with bows and arrows--if the filmmakers could think of it, they put it in the movie.

There is also a journey waiting to be completed. Shiro has a last chance to save himself, and in so doing preserve the innocent. The good women of his life--his mother and his two love interests--are both on hand to encourage and cajole, and they being the only ones not being tortured suggests that they are not meant to be there, and perhaps Shiro completing his goal will save them as well. His quest requires him to traverse the pitfalls of Hell, often walking against the tide of sinners, following the sound of the crying baby in order to rescue the child from being lost to evil. This baby is actually his and Yukiko's unborn child.

It all gets pretty freaky, and there is enough blood in this cinematic damnation to make up for the bloodless set-up. Though the special effects are clumsily theatrical by today's standards, the rawness of the expression actually invokes the primal source from which the frights emerge. Thankfully, even with the religion at the base of this picture, Nobuo Nakagawa also manages to keep Jigoku from being at all moralistic, allowing us to just enjoy his lurid imagination without having to take a lesson away from it. Actually, if one wanted to, the ambiguousness of the final shots could even be argued to reinforce a notion that all of this is meaningless and there is nothing beyond the life we live on this plain. Shiro caught in a circular struggle cuts us off before the predictable narrative closure can be achieved, and the camera returning to the lifeless bodies at the scene of the death, drifting over to the painter and the portrait of Hell he had been working on, reminds us that this is just a vision and nothing more. It's as if seeing Ensai's nightmarish creation inspired nightmares in those who have just passed into eternity's dreaming, but in the waking world, they remain exactly where they fell.

No comments:

Post a Comment