When discussing the French New Wave, the two names that invariably come up first are Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut. Arguably the most famous of the directors from that very loosely defined school, they also represent divergent artistic approaches that converge in terms of intent even if not always in style. Of the two, I find Truffaut's storytelling style to be cleaner, less irascibly experimental, more concerned with making old formats say new things. Both directors flirted with genre, but whereas Godard stepped inside each style only to dismantle it, Truffaut was more willing to find how his own voice and genre convention could work in tandem. Truffaut worshiped Hitchcock, and the two of them had extended conversations that now serve as a sort of Bible

Truffaut first dabbled in the criminal underworld nearly a decade before, in 1960, when he chose as his second feature to adapt a novel by David Goodis, author of the original story that became the Bogart and Bacall film Dark Passage

Real-life music star Charles Aznavour plays Charlie Koller, nee Edouard Saroyan, a piano player in a dive bar on the Parisian side streets. Charlie is hiding there from his former life, one that comes crashing back when his lug of a brother, Chico (Albert Remy), shows up one night while trying to outrun a couple of hoods. He doesn't understand why his little brother is playing in a bar under a fake name when he could be playing concert halls. This is a question that Charlie would rather not answer; he's put a lot of time into being a man without a past, and he doesn't like being exposed to his nosy boss (Serge Davri), his co-workers, or the joint's regulars. Thankfully, the hoods come busting in before big bro Chico, lumbering around like a Marx Brother that's been fed too much corn and steroids, can completely spill his guts. Even so, the damage is done, questions have been raised.

The tough guys chasing Chico are my two favorite characters in Shoot the Piano Player. Chico first describes them as two men, one wearing a hat and the other wearing a cap, both smoking pipes. And, sure enough, when the pair come strolling into the bar, the description fits. Momo (Claude Mansard) and Ernest (Daniel Boulanger) are talkative and bumbling, coming off more like accidental criminals rather than hardened hoods. They struck me as the wayward cousins of the twin police detectives, Thompson and Thomson, in the Tintin comic books. Though Chico may have eluded them, they now know about Charlie, and they try to muscle him and the waitress who has a crush on him, Lena (Marie Dubois), into giving up the fugitive's location. When that doesn't work, they kidnap the youngest Saroyan boy, Fido (Richard Kanayan), who finds it no more difficult to trick the gangsters than Lena did.

At the center of all of this is Charlie, an atypical noir villain with a typical noir problem. Like the many anti-heroes of the Hollywood films of the 1940s and '50s that comprised the noir filmography, Charlie is trying to bury a past that would be much better forgotten. Unlike the guys regularly played by Burt Lancaster and Robert Mitchum, however, Charlie's misdeeds are not exactly criminal, not in a legal sense. He was happily married to Theresa (Nicole Berger) when fame came a-knocking, and the twin maladies of being hungry for success and cripplingly shy left Charlie little time or energy to pay attention to his wife. His disinterest drove her to drastic measures, and unable to live with the guilt, he gave up everything that made their untenable situation possible. He traded the fame of Edouard Saroyan for the obscurity of Charlie Koller.

Lena actually already knew about Charlie's secret identity. In my review of Malle's The Fire Within, I commented that women were attracted to Alain because they saw a man in need of mothering, and Lena probably has a little of the same attraction to Charlie. He is a wounded bird who needs his heart mended. She is also attracted to his sensitive, artistic temperament, which she thinks makes him different. Charlie fears that he isn't different enough, though, that he is exactly like his brothers, and that he is just a thug and a thief. In a slightly ironic twist, Truffaut reveals that this is not something in the Saroyan blood, there is no genetic predisposition for malice, as Charlie's parents are decent, upstanding people. So why would fate decree that the new generation would be different?

Because fate does have other plans for Charlie, it would seem. His life always goes wrong when he tries for something more than the working-class life that his siblings have settled into. His first bid for musical stardom ended in tragedy, and though when Lena convinces him to return to the concert halls she means to liberate him, fate reaches down and smacks him in the face again, reminding him to be who he is and not get any ideas about being anything more.

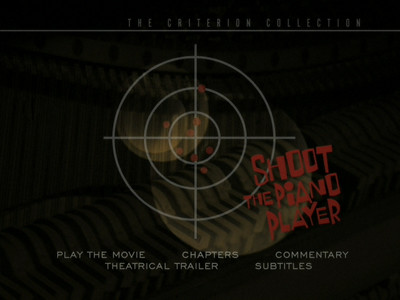

This is not a problem for Truffaut, who stretches his creative legs in Shoot the Piano Player and ends up putting together a fun, freewheeling crime picture. Shooting with cinematographer Raoul Coutard, he creates a lovely black-and-white portrait of the Paris underworld, of the juke joints and the late-night streets, the cramped apartments and the grander, open expanse of the city that surrounds them. Traditional modes of exposition are dropped in favor of more playful techniques. Aznavour's voiceover only comes on to express the character's doubts, particularly when he is wondering if he can score with Lena, and when some of the more dastardly news is delivered, it's shown as humorous asides, the action cameoed in the center of the screen. (The title change--the original novel was called Down There--could even be seen as a cinematic pun: shoot him with a camera, shoot him with a gun.) Of the more conventional storytelling aspects, Charlie's past catching up with him and the flashback to his disastrous marriage, the traditional wrapping delivers the most unexpected twist: that Charlie is not the tough customer we assumed of him.

In the end, though, the other conventional element of Shoot the Piano Player is less successful for feeling a little too automatic. The Saroyan family runs a farm outside of the city, and when Momo and Ernest finally catch up with them, the resulting shoot-out comes off as more compulsory than necessary, a required end for a loosely structured movie that hadn't done anyting required of it before this. In a way, this final showdown reminds me some of the seclusion of the similar ending in Godard's Band of Outsiders, and the snowy terrain, gorgeously shot by Coutard, also served Truffaut better all those years later in Mississippi Mermaid. Thematically, the events in this climax do advance the story, however; the consequence of the clash is what forces Charlie to accept his fate. It's almost Promethean in its repetition, and given that the fire Prometheus gave to man could be seen as a metaphor for the creative spirit, it's not too far fetched to tie the piano player's punishment to the greater myth.

Life goes on demanding a price, and Charlie goes on paying it. As Charlie's lost wife told him, "What you did yesterday stays with you today."

ADDENDUM TO SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER AND THE FIRE WITHIN: I usually try to watch bonus features after I've written my review, to try to formulate thoughts and reactions on my own rather than pilfer from others. Tonight, I was finally watching Jusqu'au 23 juillet, an excellent documentary on The Fire Within that compares and discuess Louis Malle's film and the Drieu La Rochelle novel its based upon, and in one portion, actor Mathieu Amalric (The Diving Bell and the Butterfly) is talking about how Alain is noticing the vast details of life, searching through the minutiae for a reason to have some hope. He mentions Alain looking through his window at a girl walking in the street with a violin. When they cut to the scene, the girl made me think of a similar young lady in Shoot the Piano Player, a musician who has just finished auditioning for the man who will become Charlie's agent. She walks out listening to him play, carrying her own instrument. They could almost be the same girl, she could be leaving Charlie and walking home, passing by Alain.

Also, in another clip, we see a copy of Babylon Revisited & Other Stories by F. Scott Fitzgerald sitting at the front of a stack of books in Alain's room. A detail I completely missed on my own! I guess I was on to something!

No comments:

Post a Comment