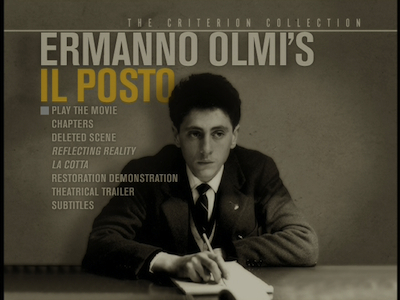

Criterion fans know the name Ermanno Olmi from his excellent Neorealist films, Il posto [review] and I fidanzati [review], small dramas set in then-modern times (1961 and 1962) that are elegant, personal, and focused. And if that, like me, is all you know, then his Palm d’Or-winning The Tree of Wooden Clogs may be a bit of a surprise. Released in 1978, this three-hour-plus drama is modestly epic in scope, more open in approach, and yet surprisingly just as engaged with the personal.

Set in Italy's Bergamo province at the tail of the 19th Century, The Tree of Wooden Clogs tells a season in the life of a farming village. At the time, peasants lived as sharecroppers on a wealthy landlord's estate, working his fields, keeping 1/3 of what they produced, giving the rest to him (see also Bertollucci’s 1900 [review] for a similar scenario). The farmers shared one community building, four or five families per, individual tribes within a larger conglomerate. As his narrative progresses, Olmi dips in and out of different families in one particular dwelling, mining their collective stories. There is the young man looking to woo his neighbor's daughter, or the old timer looking to beat the others to the tomato harvest, and the various wives and mothers keeping their children in clean clothes and nourishment. Each action is individual, but it also adds to the whole. No one family, no patch of land, is an island. Or, to change metaphors, The Tree of Wooden Clogs is a tapestry, and each singular weave somehow ties back to the center, and you don't see the full tableau until you step back and take it all in.

The closest thing we have to a central family is the clan whose challenges give The Tree of Wooden Clogs its name. This incident is a small story embedded in the whole. The family’s young son, Minek, is a bit of a prodigy, and the parish priest insists his father send him to school, even if it is a four-mile walk each way. On one such trek, the same day his baby brother is born, the child breaks one of his clogs. His kindly father doesn't scold him or make a fuss. Instead, he sneaks out into the night and cuts a chunk of wood from a tree alongside the road. It's unclear whether he takes to this task quietly so as not to disturb the boy's mother, still recuperating from the birthing, or because he's taking the wood without clearing it with the landlord. All we feel is there is something momentous and heavy in the act, especially as he begins his carving while the rest of his family says their evening prayers. Is this plea to the heavens to be his absolution?

This

is how connected everything is--religion, birth, survival. Within the

relatively short period--short in the context of an existence, at least, because

make no mistake, this is a long movie--we see the full circle of life. Crops

are grown, animals slaughtered, children born. We see only a small sliver of

the other side, a brief peek into the landowner's life. We see how faith holds

sway, even when impractical. We also catch a glimpse of political tides to

come. But as large as the land and the sky and the whole of the world may

appear, it's still the little things that matter. The simple pleasures.

Olmi applies the Neorealist method to great effect. Like Roberto Rossellini did with the Sicilian fishermen for Stromboli [review], or even Michael Powell and the Scotsmen on The Edge of the World, the director worked with the real people of the Bergamo region, even having them speak in their native Bergamasque. The landscape of The Tree of Wooden Clogs is not populated by actors, but the actual citizenry of the world Olmi is capturing. Yet, they still are actors, aren't they, since they live in the now while dressing up to play their ancestors in front of a camera. Such is the illusion, and so powerful the effect, you'll be forgiven for how often you'll forget you are not watching a documentary. The details are real, and often not for the squeamish (if you've never seen a goose or pig butchered...), and the script so absent of point-A/point-B plotting, the final cut has the feeling of real life, not a cinematic construction. Like life, it can be a bit of a haul to reach the end, but hopefully we’ll all find both tasks worth it. (Though I’m not holding out much hope for this living business...)

Olmi applies the Neorealist method to great effect. Like Roberto Rossellini did with the Sicilian fishermen for Stromboli [review], or even Michael Powell and the Scotsmen on The Edge of the World, the director worked with the real people of the Bergamo region, even having them speak in their native Bergamasque. The landscape of The Tree of Wooden Clogs is not populated by actors, but the actual citizenry of the world Olmi is capturing. Yet, they still are actors, aren't they, since they live in the now while dressing up to play their ancestors in front of a camera. Such is the illusion, and so powerful the effect, you'll be forgiven for how often you'll forget you are not watching a documentary. The details are real, and often not for the squeamish (if you've never seen a goose or pig butchered...), and the script so absent of point-A/point-B plotting, the final cut has the feeling of real life, not a cinematic construction. Like life, it can be a bit of a haul to reach the end, but hopefully we’ll all find both tasks worth it. (Though I’m not holding out much hope for this living business...)

The span of The Tree of Wooden Clogs only

grows macro in its third hour, when the young couple we’ve watched court one

another gets married and goes off on their honeymoon. Traveling with them, we

see nearby townships, and people beyond the landlord’s property line. These new

elements almost seem cartoonish by comparison, so used have we come to the

quiet life within the farm. The honeymoon itself passes without much

fanfare--at least until the newlyweds return home and, immediately after, other

narrative threads finally start to pay off--some good, and some bad. I suppose

it’s up to each viewer to divine where Olmi is coming down in terms of the

divine and its relation to what happens to the peasants, or what that also says

about the nature of small community. A sad fate befalls Minek’s family, one

that is swift and without recourse. As neighbor turns away from neighbor and

relies on prayer rather than intervening, I found myself caught between my

empathy for their resorting to their faith due to a need for some kind of

explanation of why life is cruel and my more visceral reaction. I can’t help

but think they are using religion to sidestep their responsibility toward their

fellow man, and that this is perhaps why the cycle of the wealthy oppressing

the poor continues. (“I’ve got mine, let God take care of the rest.) One could

surmise this is why Olmi includes glimpse of the socialist revolution on the

rise. Certainly nothing happens on screen in The Tree of Wooden

Clogs by accident, given that the director, in the truest auteur

fashion, is credited with script, photography, and editing. Just as the hands

of the farmers draw riches from the land, Olmi’s hands draw out this

mis-en-scene. Soil has never been so beautiful, and yet so daunting. Soft and

brown when giving life, dark and muddy as the day grows hard.

Yet, for the filmmaker to add any editorial or exposition

would be to betray his motivating conceit. The Tree of Wooden

Clogs is meant to be an observation, not an explanation. It’s a

morality play without a coda. The staging, the lighting, everything is as

natural and real as is possible in the confines of a motion picture construct. The

camera itself seems to disappear in the crowd. The light is never brighter than

the hazy grays the sun provides. The visual story is limited to what the eye

can see, the same way it would be were this a newsreel. Olmi doesn’t dress the

set, he doesn’t call attention to the design of his shots, he doesn’t zoom

emphatically. His approach is as straightforward and quaint as the daily life

he is chronicling. It’s also as intimate, and therein he finds his truth. From

the supplements accompanying the movie on this disc, especially the British

television special from 1981, we hear how the film was inspired by stories the Olmi’s

grandmother told him about her life, and so we can see that the director’s

exacting methods are born of a personal pride. He is reaching back into his own

history, digging for the roots that would eventually put him on his own two

feet and lead him here.

This disc provided by the Criterion Collection for purposes of review.

This disc provided by the Criterion Collection for purposes of review.