Is there any better signal that someone has reached the end of their emotional rope than their having to evoke their own humanity? Second-eldest son Ryota Yokoyama, played with brittle stoicism by Hiroshi Abe (Survive Style +5

Still Walking is a family drama. It examines the exclusive, shared world that can only be created through blood ties. In the Yokoyama clan, father (Yoshio Harada) is a retired doctor, set in his ways and grumpy about those ways. He wanted his boys to take over the family business, but one died and the other restores paintings for a meager living--and is in the process of failing. It's one of the many criss-crossing lines that the characters fail to see. They are too close to one another to realize the gap in their years doesn't mean they don't share common woes. Both the father and son fear their own obsolescence. The old man, Kyohei, no longer sees patients, and Ryota's occupation is becoming increasingly marginalized. Both need the validation of their work, yet neither is willing to acknowledge that need in the other.

Arguably, this is the central frustration that exists in all families: the need for one another vs. the way we tear each other down. Kore-eda expertly portrays the dual edge of this kind of shared experience. Still Walking is full of wonderful moments where ritual and memory come into play. There is an ease in which the relatives fall into their old ways. The smell of their mother's corn tempura reminds them all of years of sharing the same meal. Some remembrances tied to this food are exactly the same, some vary in detail from person to person. The differences are small, but they matter. Something Ryota said being refurbished to demonstrate how funny Junpei was creates a deep cut. At one point, the sister, Chinami (You), breaks down because of a petty comment from her father. He slights his wife (Kirin Kiki), insisting it's his hard work that built their home, though it's clear without anyone pointing it out that her constant toil is what has kept it together. (Don't you worry, she gets her own back later. Boy, can these two old folks bicker!)

As with any story about a group of "veterans" who have been together for years, a new sounding board for old grievances can be introduced into the narrative via rookies. Still Walking does this through Ryota's new wife, Yukari (Yio Natsukawa), and her son Atsushi (Shohei Tanaka). Yukari is a widow, so this is her second marriage, and the rest of the family whispers over Ryota's choice. Is a widow really the best spouse for someone who has never been married before? Ironically, it seems that their fear is that the dead husband will always be around and that Ryota can never get comfortable in his marriage bed. It's another crossover the Yokoyamas don't get at first, not until the subject of Junpei's widow comes up. It's a sad moment, and though we wish that the characters would stand up for themselves and each other with more force, the reason Still Walking is so good is because Kore-eda isn't afraid to let the film be achingly human. Later, when Yukari expresses how she feels like an outsider, Ryota shows little empathy, instead defaulting to defend his family. It kind of makes you want to smack the guy, especially as he got so upset when the family was viciously making fun of a practical stranger, the boy whom Junpei rescued from drowning, leading to his own death. It's a terrible error, but an all too obvious foible: he sees the boy's faults as his own.

In truth, this is the way people are. They do stupid things. Things that make us want to reach out and grab them and shake them and make them see their own error. The way we might with our own brother or father or mother. Kore-eda, for all intents and purposes, has made us one of the Yokoyamas. We care about them enough to be frustrated by them and to want them to do better.

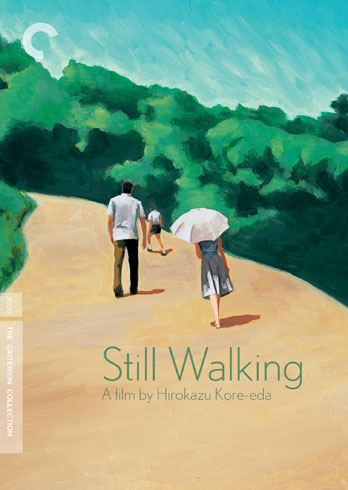

Still Walking isn't very complicated in terms of presentation. It's a film where everything is under the surface. One has to watch and listen and experience what is being said and done and let it sink in to fully grasp all that is buried just below what's visible. Not much happens in the movie--most of it is the family sitting and eating, eating, eating--but so much happens that it's impossible to get it out of your head. Ozu is always the easy comparison when dealing with a film like this, but it's because he was so good at presenting common drama in an unfussy manner, there really is no improving on his standard. Ozu regularly took us into homes in much the same way Kore-eda does here, but the elder director kept us at a respectable middle-distance. Hirokazu Kore-eda and cinematographer Yutaka Yamazaki use the Yokoyama home as their primary set, letting the walls create a cramped intimacy. The relatives are often on top of one another, and so the camera is also on top of them. Tight framing allows for tiny conspiracies. Mother and daughter might share a bit of gossip while their father is just out of frame, or a little boy tries to hide his laughter by ducking below the common eyeline. Frills are kept to a minimum. When outside, Yamazaki gives us wide shots to show us how the world is vastly larger than the Yokoyama dinner table might make it seem, yet he doesn't go sweeping out across the rooftops. The actors stay in the image. For as much as life extends beyond them, they are an inextricable part of it.

Still Walking has a bittersweet ending, expertly seasoned to taste just right. Some progress is made in the farewell, enough to make everyone feel good about themselves, but then private thoughts show how far off they still are. Life is often a series of compromises and conciliations, massaging the situation just enough so that we can walk away with our dignity. It's there in the title, itself a reference to a pop song the mother plays in the movie. The romantic ballad at once wrestles with past heartbreak and pushes for new hope. Kore-eda uses it as a centerpiece to his film, like a mini narrative within the narrative, almost like instructions to his characters for how to cope, a signal that they are not alone in their desires and fears. Once this is done, they can get on with their story, which will then serve as instruction to the rest of us.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

No comments:

Post a Comment