Ting-Ting: “Then who needs movies? Just stay home and live life!”

The Taiwanese film Yi Yi is, in fact, about life, but it also reminds of us why we actually like movies, too. Edward Yang’s 2000 feature has an epic length, but a most human scope. Clocking in at nearly three hours, this family drama takes its time looking around in the lives of the Jian clan. It begins with a wedding and it ends with a funeral, and Yi Yi covers all the ups and downs in between--though really, rather than being pointed peaks and valleys, the graph of this narrative would be more like a wavy line. True life isn’t that sharply defined.

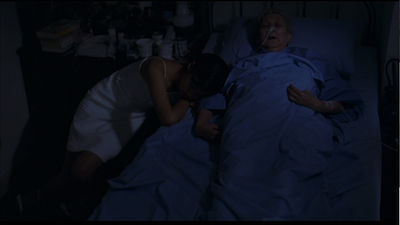

A lot happens in Yang’s opening sequence. The basic relationships are laid out and the various emotional conflicts indicated. A-Di (Xisheng Chen) is marrying Xiao Yan (Shushen Xiao), who is in an advanced state of pregnancy. Apparently, A-Di jilted his long-term sweetheart Yun-Yun (Xinyi Zeng) to have his affair with Xiao Yan, and his mother (Ruyun Tang) has not forgiven him and goes home before the reception. She lives with her daughter Min-Min (Elaine Jin) and her husband NJ (Nianzhen Wu), and the old woman has a stroke while everyone is partying, an event that her granddaughter, Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee), blames herself for. Grandma collapsed taking out the trash, which was Ting-Ting’s job. She fears her bad behavior is why the old woman is in a coma, and if she can be good long enough to earn her forgiveness, Grandma will wake up.

Meanwhile, the Jian men are having women trouble, it’s not just A-Di. NJ runs into his high school sweetheart, Sherry (Suyun Ke), in the lobby of the hotel where the reception is being held. She is visiting from America, where she moved after NJ broke her heart without explanation. Maybe the father’s sins have been passed on to the son, then, and it’s karmic retribution that is causing little Yang-Yang (Jonathan Chang) to always get picked on by girls. Yang-Yang is an interesting character, as he mostly stands apart from the rest. His dramas with other kids and the dean at his school are his own thing, and his exploration of new experiences is different than the rest of his family, who are mostly dealing with what they already know. The grandmother’s poor health, for instance, puts her daughter on a spiritual quest and makes Yang-Yang’s sister question her moral health, but Yang-Yang is asking philosophical and scientific questions. He is trying to figure out how it is we look at the world the way we do.

Which, when you think about it, isn’t all that different than what all the others are trying to figure out. How did I get to be this way, and why doesn’t it make me happy? Long after she ponders the pointlessness of cinema, Ting-Ting asks, “Why is the world so different from what we thought it was?” In Edward Yang’s fictional reality, it’s not really an either/or proposition, everything is of one piece. It’s why he named the movie Yi Yi, which literally translates as “One One,” but it’s also meant to be like a band leader counting off before a song. “A One and a Two...” is kind of the official translation, or more like a subtitle. As Yang explains in his press notes, life is about ones and twos. It’s all the same, and all separate, both apart and joined all at the same time. Each new moment can also be a potential new start.

Thus, a spiritual journey can easily run alongside a more logical examination and mother and son can end up in the same place. Or, in one of Yi Yi’s most touching sequences, Ting-Ting goes on her first date ever at the same time her father goes on what is the first date of his second chance. Both nights out are remarkably similar, and they end with heartbreak and confusion. Yet, for all of these coincidences and shared experiences, life itself is seemingly random. Why else, then, would the screw-up brother A-Di stumble into good fortune despite squandering so much, and Ting-Ting have such trouble despite her attempts to be good? Amidst all these criss-crossed romances and bruised feelings, there are no real checks and balances. Things go one way or they go the other. A one or a two.

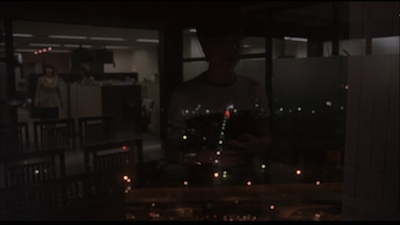

There are many modern movies one could compare Yi Yi to. In some ways, the dissatisfaction and the potential dangers of the different personal quests remind one of Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm [review]; in how the family works as a unit partially because of how badly the pieces sometimes fit together brings to mind Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Still Walking [review]. Edward Yang approaches his material with more patience and editorial distance than either of those. His work is less stylized than Lee’s and more open than Kore-eda’s. He uses multiple points of view to get at the truth--peering around corners, looking across corridors, and examining reflections to search out what might otherwise not be seen. Young Yang-Yang has a theory that we can only know half of what is real because we can only see what is in front of us. So, he goes around photographing the backs of other people’s heads so they can see themselves as only others can (the DVD cover makes even more sense once you see the film). In this way, the writer/director also seeks out the answers his characters may never find.

Which isn’t to say that Yi Yi is without mystery either. There are some things that Yang isn’t going to put too fine a point on--Sherry’s lonely decision and the origin of the paper butterfly, to name two. Like I said, life is not that sharply defined. The important thing is that the filmmaker doesn’t forget the individuals who stand in this sea of questions, and in so doing, doesn’t allow them to forget themselves.

There is a beautiful realism to how Yi Yi is put together that supports these intentions. Weihan Yang’s photography has a delicate beauty, draping light in thin layers over the scenes so that even though everything looks real, it has just the right polish. Loneliness, both public and private, is often given a wide frame. More than once, we spy a shared moment from outside a café window. Only at important times will we get closer so that the camera may regard the quiet hurt. It’s always a gentle intrusion, and the creative Yang duo often lets the characters hide in the shadows at those moments--NJ in his hotel room, Sherry in hers, Min-Min looking at her face in the window glass. It’s not voyeuristic so much as it is respectful.

The cast also deserves special note. It’s hard to regard most of these people as actors, as these aren’t performances where you can really point to technique or mannerism. Only the more comical subplot with A-Di and his two women seems put-on, something Yang intentionally underlines when A-Di relates his ludicrously embellished story of how he got his money back. The young actors in particular avoid any of the usual tricks and foibles of their age. Kelly Lee manages to give Ting-Ting private, silent aches without resorting to emo whining, and Jonathan Chang’s Yang-Yang is charming without ever being precocious. His eyes drink in the world, but he never vomits it out the way so many child actors are so often called upon to do.

Yi Yi is stitched together with such elegance, the careful structuring is nearly imperceptible. It’s a story with deep resonance, its themes and its situations traversing culture and touching on universal meaning. There is much to rewatch here, reasons to revisit, ponder, and explore. There are no platitudes extended at its end, no epiphanies or even reconciliations, yet the viewer is left with something far more substantial than they might find in a film where the connective tissue is more pronounced. It sweeps by like a breeze, easy and calm, but if you take a look around, Yi Yi has left plenty behind. It’s the unique pleasure of cinema, how seemingly quickly it comes and goes, but how long it really lasts. It’s why we watch movies, why we now let them into our homes. The visceral pageantry makes it feel like we are seeing our own lives reflected in the glass.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Please Note: The screengrabs used here are from the original Criterion standard-definition DVD of Yi Yi, not from the Blu-Ray.

No comments:

Post a Comment