Criterion is about to re-release two of its earliest Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger DVDs, and while the much vaunted restoration of The Red Shoes is gobbling up most of the press clippings [read my review of the theatrical print here; the DVD review here], I sincerely hope Black Narcissus won't get overlooked. Because despite the lack of pre-publicity for this particular restoration, the new DVD transfer for Black Narcissus is astounding. The storybook Technicolor has such marvelous hues and textures, it's like the Archers--alongside cinematographer Jack Cardiff--have invented a world as illusory and new as James Cameron's Avatar [review], only they did it more than 60 years ago and with a completely different spiritual message. To have a DVD that finally shows us the natural pigments and the level of detail intended by the filmmakers is a great boon.

Compare the above: top image is 2010, bottom image 2000

Released in 1947, Black Narcissus is based a novel by English author Rumer Godden, who is maybe best known for The River, her memoir about spending time in India as a child (later made into a film by Jean Renoir). For Black Narcissus, she takes readers high into the Himalayas to tell a story of an order of nuns assigned to a temple 8,000 feet in the air. They have been invited by the local ruler, a peacock they refer to as the Old General (Eamond Knight), though there is some doubt that it's the best place for a convent. A group of monks tried to set up shop the year before and barely made it through a couple of months.

The nun put in charge of this new cloister is Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr), and it will be her first leadership assignment. Accompanying her are four other sisters: Philippa (Flora Robson), chosen for her gardening skills; Briony (Judith Furse), who is strong and experienced in medicine; Blanche, a.k.a. Sister Honey (Jenny Laird), popular for her kindness; and the troubled Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron), who needs a change of pace to get her head in order. The mountain castle is the wrong place for it, however; none of the women are prepared for the way the new environs will change their lives.

Top: 2010, bottom: 2000

The Old General's castle--which, ironically, is where he used to keep his harem--sits above a valley, and the nunnery will serve the village below, providing a school and health clinic for the locals. The people lead simple lives, most of them work in agriculture. On one side of their moral spectrum, they have a holy man who occupies a high point near the castle, where he sits and meditates day in and day out; on the other end is the only Westerner in the area, a man named Dean (David Farrar). Mr. Dean is the one who tried to warn the sisters away, but if they are going to be there, he is going to give them a hand when he can--sometimes whether they like it or not. He's not afraid to tweak their piety for a laugh.

A story like Black Narcissus will usually go one of three ways: the nuns can either change the people they have come to help (bringing the heathen salvation/taming the savages), or the people can inspire a change in the missionaries instead. The mawkish third option is that both might happen. Powell and Pressburger go for a fourth option, choosing instead to make the locals only a small part of the story. The natives of the area are a product of their environment, and it's the environment that will change the nuns. The sisters have come from an order that believes hard work is the way to salvation. Toil distracts the mind from earthly things, leaving more brainspace for God. The culture clash is more mystical than social, as emphasized by the Archers layering Western religious music over Eastern religious imagery. The mountain retreat is isolated and magical, like a version of the fabled Xanadu, and in its nest, the nuns will surrender to their interior desire. Isolation creates distraction rather than fostering peace. Philippa, for instance, plants flowers instead of vegetables, choosing beauty over nourishment.

For Sister Clodagh, this new space brings back memories, and we see flashbacks to her life in Ireland before joining the faith. She dreams of a past that is equal parts hurt and nostalgia, and though we only see snippets of what happened, we sense that any happiness in the events are short lived. One of the flashbacks even ends with Clodagh disappearing into darkness, swallowed by the sky, an image that prefigures the final shot of Black Narcissus, when the castle disappears into the clouds.

Whatever is eating at Clodagh, it isn't helped by the presence of Dean. The rugged man of the wilderness is a most masculine figure, and his magnetism is irresistible to both Clodagh and Ruth. This central triangle forms the crux of the movie's plot. By comparison, the side story of the local girl (Jean Simmons) that Dean might have romanced and the Young General (Sabu) who stirs things up with his fancy clothes and perfumes almost seems like an afterthought. There are themes here reminiscent of the Audrey Hepburn drama The Nun's Story

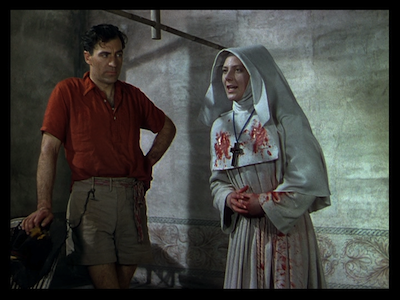

And I mean that literally. From the get-go, Ruth is presented as the one out of sorts. She belittles the village children and is so pale and sweaty, she looks like she is going to die in her habit. Her lust is presented as a literal fever, one that only increases the longer she is in the mountains. Dean shows her an early kindness, and that's all she needs to fixate on him. The fact that she's covered in blood when it happens--an early introduction of a red color scheme associated with the character--should be an indication of what kind of figure she will come to represent. Black Narcissus is a romance cross-bred with a horror film, and its melodrama has as much in common with the histrionics of Hitchcock's Rebecca [review] as it does any of Douglas Sirk's soapy tearjerkers. The women are from an order where the nuns renew their vows every year, and Ruth doesn't re-up when her time is through. Instead, she puts on a dress and make-up smuggled from the city thinking that she will be able to stay with Dean. When he refuses, she blames Clodagh for stealing him and goes after her rival.

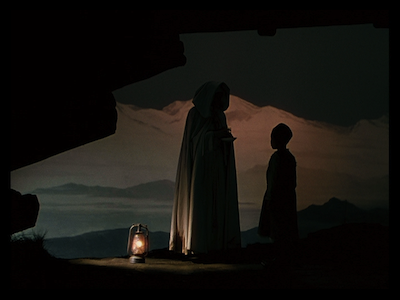

There are intimations that the wind and the altitude have infected Ruth's sanity. There is also an understated element of magic at work. A young child's death has turned the villagers against the nuns, believing the medicine they gave her to be responsible. When Ruth goes over the brink, the local men are playing their drums, holding a ritualistic vigil...but for whom? Earlier in Black Narcissus, they did the same thing when the Old General was on his deathbed, and they only stopped when he died. At the time, the noise got on Ruth's nerves. Is it now compelling her to have this psychotic break?

When Ruth gets dressed up for her new freedom, both her frock and her lipstick are red. She also lets her fiery hair out from under her white habit--and it's probably worth noting that Clodagh has red hair, too, making them twins after a fashion. The more deranged Ruth gets, the more red her eyes get, culminating in a close-up that shoes them rimmed with crimson and shining with insanity. She also passes out when Dean rejects her, and the shot is framed from her point of view as the entire screen goes blood red. The filmmakers use red for all its various connotations: passion, heat, life. Color is almost like an added element of nature in this opera; it signals change, hence the colorful transformations of the season. Red marks Ruth's change, but her final metamorphosis comes when she finds Clodagh alone and unprotected. Ruth is so drenched in humidity and sweat, her dress and her hair have turned as black as the shadow that surrounds her. As black as the shadow that devoured Clodagh in flashback.

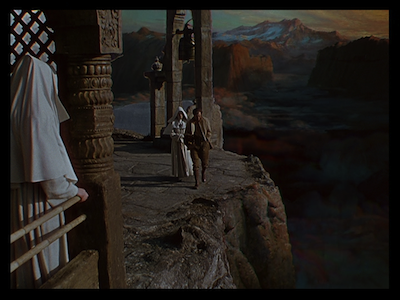

The visual design of Black Narcissus is as beautiful as any the Archers ever created, rivaling even their stage-based dramas The Red Shoes and Tales of Hoffman. The vast landscapes they dream up and invent on the backlots of Pinewood Studios are glorious in their detail and realism. Using every tool at their disposal, including trompe l'oeil matte paintings, they create distance and depth. The seclusion of the nunnery is made very real by the magnitude of the mountains that surround them and the terrifying drop that awaits them at the edge of their property. When Clodagh stands at the bell tower, the cliffside goes all the way down into the valley, but we can't even see the bottom. We're too high, and there are too many obscuring clouds. It's an illusion as believable as any of the CGI cities Christopher Nolan builds in Inception [review coming Thursday]. The mind boggles at what the Archers might have done with computers at their disposal. The digital age is certainly being kind to them, as the gorgeous image quality of this DVD will attest.

Of course, in a movie of this kind, color is not just part of the background, but also part of the politics. Black Narcissus walks a fine, antiquated line between treating different ethnicities with respect and slipping into racial clichés. Seeing Jean Simmons and Esmond Knight in brown face is a little hard to get used to, and the script never quite gets past treating the villagers as "the other." Dean's description of the locals at the start of the picture is respectful, but he's typically colonialist in action. Yet, there are subtle moments where prejudiced points of view are satirized and even ridiculed. When Ruth, for instance, insists "they all look alike," there is an undertone that makes her seem ridiculous, even if no one ever comes out and says it. Even more subversive is seeing the nuns teaching the children English using symbols of imperialism. Namely, a chart of weapons! In the sly smile of the young translator Joseph Anthony (Eddie Whaley Jr.) are the early sparkles of revolution.

That said, for everything that is below the surface, the most memorable undercurrent will be the unrealized romance between Mr. Dean and Sister Clodagh. In typical movie fashion, the two are at odds from the start, trading barbs that are at turns humorous and rueful. Dean can't stand Clodagh's being clueless, she can't stand his rough manner and carousing. Yet, the stronger she grows and the more he reveals himself as capable and empathetic, the closer they become. There are some smoldering looks between them, and some heartbreaking ones, as well. Like socially restrained lovers in a Merchant Ivory picture or an Edith Wharton novel, they can't act on their feelings, and so it's all in the tone of their voice and eye contact. David Farrar, who was also in the Archers' production The Small Back Room [review], is charming and funny, but he also has an earthy gravitas. His best moments are not when he is playing the rake, but when he is having to choke on the emotion he doesn't want to admit is there.

If I had to choose, I'd say this movie has my favorite Deborah Kerr performance. I like her as Sister Clodagh even more than I do in An Affair to Remember [review] or The Innocents

Perhaps it's the quiet of the earlier bits that lends credibility to the louder technique of the later ones. It certainly sets the stage for an effective finale. Powell and Pressburger have paved the way for an exit that passes us back through the veil. We depart from the magic of the mountains back into the real world, having taken a journey with their characters to someplace beyond what is familiar. We can hit stop on the DVD and return to our normal lives, but as David Farrar's last look into the camera suggests, we will probably be forever changed by what happened on this altogether unreal plane.

In addition to the new transfer for Black Narcissus, which was overseen by Jack Cardiff and Michael Powell's widow, the renowned film editor Thelma Schoonmaker Powell, Criterion offers up several new extras to make a new purchase worthwhile, whether you go with the standard-definition reissue or the new Blu-Ray

Another new extra is a short documentary called "Profile of Black Narcissus," which takes a look at the picture as a whole while also covering some of the same ground and using some of the same source material as a holdover from Criterion's 2000 DVD, the Jack Cardiff tribute "Painting with Light." Also leftover from before is the excellent audio commentary featuring Powell and his biggest fan, Martin Scorsese.

This disc was provided by the Criterion Collection for purposes of review.

3 comments:

While I save most of my passion for black and white films, this has become without a doubt my favorite color film. Not sure I find your write-up entirely satisfying. The extraordinary climax, with Sister Ruth stalking Sister Clodagh, reminds me less of a horror film and more of a German Expressionist (horror) film. The issue of Esmond Knight and Jean Simmons portraying ethnics is, for me, trivial, their appearance is as superficially cosmetic as is shooting the film in Great Britain as opposed to the Himalayas. Rumer Godden preferred THE RIVER over BLACK NARCISSUS, in large part because it spoke to her more accurately about her life experiences in India, and I can appreciate her assessment of the two films for that reason. However, she was unable to acknowledge the aesthetic beauty of BLACK NARCISSUS, however fabricated it may be, a film enhanced with a tint of fantasy yet very much rooted in very human issues, carnality, spirituality, a higher calling, the nostalgia and yearning of life's experience. I am grateful to her for having provided the source material for both Renoir's and the Archers' films, since both are truly classic, but to favor one over the other is apples and oranges, both are masterworks, and both are worth acknowledging as such (and both feature Esmond Knight).

Superlative review. It's not my favorite P&P film (that honor goes to 49th Parallel or Colonel Blimp) but it's definitely a fascinating film.

The review says:

"By comparison, the side story of the local girl (Jean Simmons) that Dean might have romanced ..."

No, Dean is her FATHER. And Clodagh understands this, as she stands there examining Kenji carefully while Dean looks on and slightly comic music plays. Then Dean says, isn't there anything you're dying to ask me? But Clodagh doesn't want to talk about it. This is why it's essential to have Simmons play the role, they needed blue eyes and European features to make that work.

Post a Comment