At the end of Sunset Boulevard

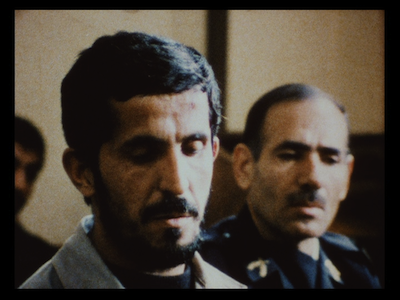

Close-Up is the story of Hossein Sabzian, a print maker who convinces a middle-class family in Tehran that he is filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Makhmalbaf is a renowned Iranian director, at the time best known for his 1987 film The Cyclist

The film opens up on a bumbling sting operation, where a reporter (Hassan Farazmand, also playing himself, as everyone in the film does) leads two police officers into the Ahankhah home to nab the alleged con man. This kick-off introduces Close-Up as a narrative construct, albeit a Neorealistic one. From a writing point-of-view, it starts with a bang, as it does drop us right down into the action--though not a typical crime movie bang. It's more of a criminal whimper, with Sabzian being carted off in a taxi cab by the arresting officers while Farazmand runs around looking for someone who can loan him a tape recorder so he can record the forthcoming interrogation. Woodward and Bernstein this guy ain't.

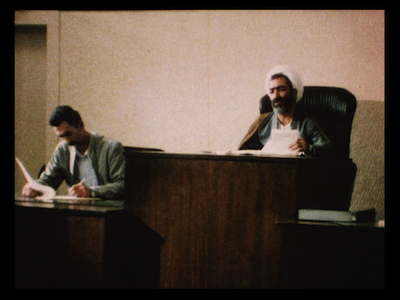

Only in the second sequence does Kiarostami introduce the notion of Close-Up as faux documentary/docudrama. Having read Farazmand's magazine article about the story, Abbas Kiarostami himself shows up at the police station to try to gain access to the faker. He wants to film Sabzian's trial, and Close-Up follows the steps he takes to get permission, first talking to the meek criminal and then seeking permission from the presiding judge. Kiarostami also interviews the family members who fell victim to Sabzian's scheme, whatever that may have been. That's something they hope to figure out at trial.

Once the court proceedings get underway, Close-Up jumps back and forth between the "reality" of the courtroom and fictional staging's of Sabzian's interactions with the Ahankhahs. As far as criminal undertakings go, Sabzian's master plan seems rather undercooked. He meets the matriarch of the family, Mahrokh, on a bus and casually tells her he is Makhmalbaf. After that, he starts spending time with the family, and the worst thing he does is borrow a small amount of money off the youngest son, Mehrdad. It takes less than week for this tangled web to unravel.

I hesitate to call the more traditional dramatic scenes "re-enactments," because essentially the entire film is a re-enactment. Sabzian did pretend to be a famous director, and the Ahankhahs were the intended victims, such as they were. Close-Up is not quite real, not quite fake--almost literally surreal in how it stands apart. It's like a distant cousin to Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman's Adaptation

Abbas Kiarostami details this story in the most unspectacular of fashions, letting most of the juicier bits be told through Sabzian's testimony rather than staging the scenes as drama--quite possibly because these are the parts of the situation that are most up to interpretation. Who are we to believe? Sabzian's stated motivation is simple enough: he liked the attention and he liked the control that being a director allowed him, even on a small scale. He would have gone ahead with trying to make a movie if the fraud went on too long, and the reason he decided to be Mohsen Makhmalbaf is that he identified with the man's films. The Cyclist, in particular, depicted real problems he could identity with, it was like watching a movie of his own life. Ironically, he is now in one. (And judging by the extras, the real-life Hossein Sabzian was getting exactly what he wanted by being in Close-Up, as well; this is definitely art imitating life and not the other way around.)

As far as the probing eye of the camera, Kiarostami's is non-judgmental. If anything, he wants us to feel sorry for Sabzian. The man is devoid of his own personality, and his life is so full of hardship, he must resort to losing himself in fantasy. Very subtly, the filmmaker also lays down questions about exploitation. Sure, Hossein Sabzian was exploiting the Ahankhah family, but they were eager to be exploited. They were eager to star in his movie, even to give up their house for him. Mehrdad loans the trickster the money not out of kindness but in order to prove he's a good guy ready to do what it takes to please a big-shot movie director. It wouldn't be heard to remake Close-Up today. The fame-seeking that Kiarostami is depicting has only gotten worse. Haven't there been reality shows about wannabe filmmakers, and aren't all reality contestants would-be actors?

The good thing about Close-Up is that, in its refusal to create an obvious separation between what "really happened" and what has been "dramatized," the film goes deeper than any reality show ever would. The big picture here is less about fame and desire, or even about the illusory art of cinema; Close-Up is far more human than that. It's a movie about true remorse and forgiveness--not redemption, that is something else. The charity given to Sabzian at the end of the movie requires real empathy and honest emotion, and it hits the viewer as hard as it hits the "character."

At one point in Close-Up, when Hossein Sabzian is explaining what kind of films speak to him, he turns to Abbas Kiarostami, who is part of the courtroom interrogation, and acknowledges how he felt a personal connection to Kiarostami's debut feature, The Traveler. The inclusion of this 1974 film on DVD 1 of the Criterion edition of Close-Up makes this a double A-side disc, a dual film release, and one that sheds some light on the kind of Iranian cinema that Sabzian identifies with. (Shame we couldn't get Makhmalbaf's The Cyclist, as well. I'm so greedy!)

The Traveler is the story of a young boy named Qassem, played by an Iranian Jean-Pierre Léaud by the name of Hassan Darabi. Qassem is obsessed with soccer, so much so that he forsakes all else and even cheats the local news seller just to buy a new soccer magazine. He's got a bad reputation at school because his mind is always on the game, and his mother is fed up with him. When his favorite team is playing in Tehran, Qassem hatches a scheme to raise money to go see them. He cons school kids by pretending to take their picture with a stolen camera, and when that isn't enough, he sells his neighborhood team's goalie nets and ball. His journey to the city ends up being an eye-opener, a glimpse of disappointment, struggle, and isolation.

Even in this early film we can already see Kiarostami's thematic concerns developing. The boy who dreams of soccer is not all that far away from Hossein Sabzian and his moviemaking fantasies. In fact, that's what Sabzian sees as having in common with the kid in the movie: this desire for something more than what they have and whatever it is that compels them to do anything it takes to achieve it. Qassem's grift with the camera is even suggestive of Sabzian's cinematic misdirection.

The Traveler was shot in black-and-white and on location, and it has the same Neorealist aesthetic as Close-Up. Though the film is lacking in extraneous fat, that doesn't mean Kiarostami shies away from the quiet moments. He juxtaposes Qassem's anxious waiting in his bedroom with the more calm, eager waiting during the bus ride. He also takes the boy from small-town life where the locals trust his family name to the big city where no one knows or cares who he is. In the end, The Traveler is more cynical than Close-Up, Kiarostami has softened over the years. The lonely figure of the boy in an empty stadium has a long way to go after all if he is to become the weeping man finding peace in the arms of his fellows.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

No comments:

Post a Comment