It's fitting that Criterion is releasing selections of the Stan Brakhage film catalogue as an ongoing anthology, as I view my interaction with his experimental short films as an ongoing educational endeavor. I finally viewed my dusty copy of By Brakhage: An Anthology, Volume One in anticipation of the release of this sequel, By Brakhage: An Anthology, Volume Two, and as I noted in my review of that set elsewhere, it was actually my second time giving the DVDs a spin. I wasn't ready to go the first time, walking in cold was not the way to enter the Stan Brakhage library--at least not for me. I needed a tour guide.

To quickly summarize, Stan Brakhage was a filmmaker who emerged as part of the underground art scene of the 1950s. His short movies were abstract expressions of his philosophy and his life experience, using pictures and light and the very medium and raw material of film to provoke and inspire the viewer into deeper exploration. Most of his films were completely silent so that, under the right circumstances, he was creating a kind of cocoon around the person watching. It's just you and the cinema, make of it what you will. From what I gather, Brakhage had specific intentions with each piece, but his real goal was making someone watch and see for themselves, and what they took away from that was just as important as any plan he could come up with.

The first By Brakhage put twenty-six of his films on two discs; the second collects thirty films on three discs. The auteur's widow, Marilyn Brakhage, has put this set together, and her approach this time is to break the work down into six programs, showcasing specific periods of Brakhage's work arranged chronologically. This is a smart move, I say. Hitting "play all" on a full two-hour run of Brakhage can be a little overwhelming, and it can be harder to identify the evolution of his work without some notation of natural stopping points. This new archival system means two shorter programs per disc, which makes for a much more manageable intake. Also, as with the previous edition, Fred Camper's film-by-film breakdown in the accompanying booklet proved an invaluable map for knowing where I was and what I was seeing.

Program 1: 1955-67: Volume Two starts with four films from Brakhage's earliest abstract period, when he first broke from his more conventional "psychodramas" (and "conventional" is a term used loosely here) and into something less grounded in traditional moviemaking. The set leads with his 1955 film "The Wonder Ring," a commissioned portrait of New York's Third Avenue, which was scheduled for renovation. Rather than taking a straightforward walking tour through the neighborhood, Brakhage uses layered images and movement to convey the sense of the city's inherent rhythm and the hidden lives that make it so vibrant. These are like refracted observances of contained existences. A glimpse at a figure in a passing window, a street sign, an address number--endless pictures, endless patterns, everything is as one.

I didn't find the second film, 1960's "The Dead," to be as successful, despite employing some of the same techniques Brakhage developed in "The Wonder Ring." Here he uses positive and negative images, as well as color, to superimpose his reactions to a graveyard and its surroundings on top of the footage he took of them. I found it to be a little obvious in its imagery. The same could maybe be said of the longest piece of the group, the 64-minute "23rd Psalm Branch" (1967), except the outcry against war in this filmic collage is powerful in its cumulative impact. Brakhage layers together newsreel footage with words and bursts of color to create a stuttering image of combat that both replicates the flicker of a television screen and the staccato rhythm of a bomb attack. He moves the frame of reference from the battlefield to real, everyday objects, and then takes it deeper, practically examining life on a molecular level. Images are equated with ideas here, and what you see will hopefully make you think about why human beings are compelled to destroy one another. "23rd Psalm Branch" even ends with a question mark: are the images of children playing with sparklers meant to create a vision of hope, celebrating a better tomorrow, or is it a warning that this is a cycle that will continue?

Grouped together, these four films show a common interest in change/mortality, a passion for life, and a curiosity about man-made landscapes.

Program 2: 1967-76: If there is any obvious thematic connection between the four films in the second part, it's creation and simulation. These shorts all combine homegrown footage with color and abstraction to create intentional sensations and to convey the formation of life and art. In 1967's "Scenes from Under Childhood, Section One," Brakhage uses flickering red shapes to create his version of the fetal point of view, while the 1976 film "Desert" features the director creating his subject where there was none. Apparently, when he arrived to his shooting location in Riverside, California, he was surprised to discover it was a suburb and not a desert town. Using light, distortion, and extreme close-ups, he makes his own barren wilderness, a cinematic illusion.

Cinema and its tools and toys were an important component of the center films in this program. "The Machine of Eden" (1970) combines the concept of a weaver's loom with moviemaking, down to the very essential sprockets and film, while "Star Garden" (1974) explores the origin of light and image showing how the sun affects life and the motion picture frame. Interesting that, in both shorts, Brakhage is linking machines and nature, equating the things man has built to the cosmic construct that is our universe.

Program 3: 1972-82: Brakhage's drive to challenge the expectation of perception and the mistaken belief that there was a single objective reality gave him a rich and varied toolbox. Any kind of footage was fodder for his cinematic missions. In this third set, for instance, we see him working with both children ("The Process" from 1972; "Duplicity III" from 1980) and animals ("Burial Path," 1978; "The Domain of the Moment," 1977). In a way, by warping these most fundamental elements of life, he was showing how easily our view of the world can be manipulated. The fact that the children were regularly his own also crosses a line between outside observance and personal confession. The way he cuts together the footage in something like "The Process" is just as dramatic a statement about cinema's ability to capture and change what can be contained in the scope of a camera lens as his photographs of nature in "The Machine of Eden." In "The Burial Path," he uses the combined montage of a dead bird and living birds to suggest that life is both impermanent and ongoing. Being mutable or cyclical is not that different, it's all flux regardless, as memorable and ultimately reductionist as the burning of the bird's coffin at the end. Here, then gone...but not gone, transformed.

Sometimes these tests can strain the interest of the audience. "Duplicity III" attempts at grand gestures, poking at our understanding of storytelling and the dishonesty of contrived presentation, but the seemingly endless footage of a school pageant eventually drags. I was going to say it's "like" watching a strangers home movies, but why equivocate? It is watching a stranger's home movies, it just happens to be a well-known artistic stranger. Some of the small touches, such as the ghostly images of the kids walking through the forest and shown as a negative image, seem like side thoughts, too brief to have impact. Almost like Brakhage is saying, "This is what you expect of me, so real quick, here it is."

The collage approach in "Murder Psalm" (1980) is far more effective for me. Using found footage from news programs, educational films, cartoons, and other less identifiable sources, Brakhage makes a facsimile of a dreamscape. Inspired by his own nightmare, it is a portrait of the brain that also serves as his impression of how the mind functions. Juxtaposing actual brain models and objects that looks like brains with images of violent people and imposing blocks of color and light, he suggests that the human mind is over stimulated, regressively selfish, and dangerous; at the same time, maybe the indulgence of these thoughts are what curbs them. In "Arabic 12" (1982), which begins to suggest at the more painterly films to come, Brakhage manipulates space in the same way he manipulated the assembled footage in "Murder Psalm." He reduces a room to glimpses of the light within it, to shapes and sparkles that pulse and flow like molecules of blood coursing through a body. It's as far from narrative as you can get, and a big step from the almost accidental structure of "Burial Path"--one could see the earlier piece as a funeral procession, from the finding of the dead bird to its ceremonial release.

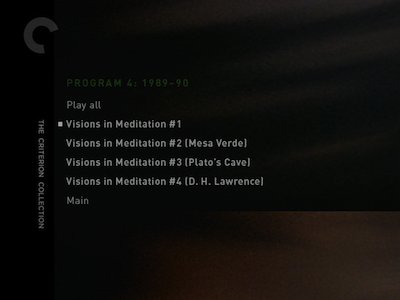

Program 4: 1989-90: This fourth grouping, found as the back half of DVD 2, breaks from convention to present a quartet of films that complete their own series. While other movies in this collection have been parts of larger works ("Arabic 12," or "Duplicity III," for example), the four-part Visions in Meditation is the first such series to be given here as a whole unto itself. These interconnected films were inspired by Gertrude Stein's poems Stanzas in Meditation

The second part juxtaposes various elements: desert followed by ice followed by blue water. The third part adds sound, matching a minimalist electronic soundtrack by Rick Corrigan to places where people sit in the glow of light bulbs and fairgrounds lit by neon. Brakhage takes his camera down into Carlsbad Caverns to evoke the philosophical concept of Plato's Cave--images of people projected on stone, do they exist? images on a screen, are they real?--while Part Four makes reference to D.H. Lawrence, going to his former home and burial ground in New Mexico. The final film in the series features dynamic skies, flickers of black blotting out the image, and movement that suggests rewinding, like we are going backwards over what we have seen. It also features the most commonplace images, including shots of suburban America. Is this meditation coming to rest? Once again, it comes down to our mortality.

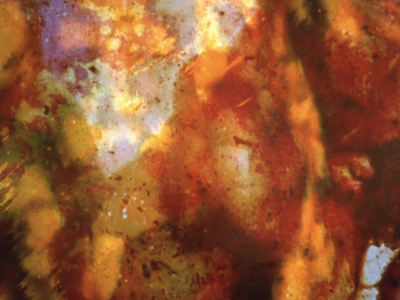

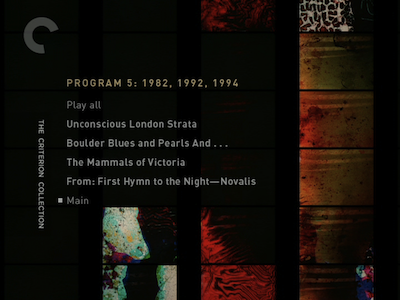

Program 5: 1982, 1992, 1994: As Brakhage moved into the later decades of his life and career, he continued to shift more into the abstract, getting more painterly in his employment of color and starting to work with his hands directly on the celluloid. His constant struggle was to replicate how the things he saw were filtered through his consciousness, to recreate the very act of looking on a primal, back-of-the-brain level. An early film in this stage, 1982's "Unconscious London Strata" is a good example of where he was going. Were the word "London" not in the title, you might not even know that was where this film was shot. Brief, distorted snaps of landmarks are only tiny clues along the path. Most of Brakhage's London consists of blurry sparkles and hues, like the literal mental record of that scene in The Rules of Attraction

1994's "The Mammals of Victoria" is more grounded in its expression, at least in the fact that it's clear that Brakhage is depicting the ocean. The film keeps coming back to shots of water, spliced in the midst of more blank and spotty artistic impressions of the same. As the film progresses, Brakhage explodes the frame with sunlight, practically setting the sea on fire.

1992's "Boulder Blues and Pearls and..." once again uses Rick Corrigan's music to add an extra layer of sensation. Footage of nature, as well as one solitary image of a coffin, give way to explosions of color, leading into the direct painting of 1994's "From: First Hymn to the Night - Novalis." Brakhage creates a cinematic kaleidoscope with paint, like a modern art piece that the artist taught to dance. Laying in lines from a poem by Novalis also suggests--along with the earlier adaptations of Stein--that we shouldn't be looking at these movies as just visual media, but as poems as well. Color creates tone, images in sequence, like alien hieroglyphics.

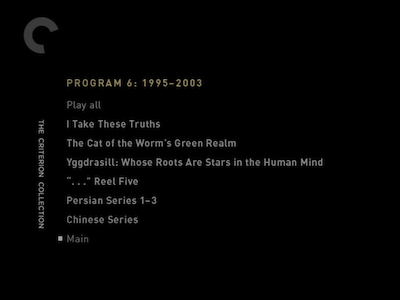

Program 6: 1995-2003: As we shift into the last period of Stan Brakhage's filmography, the conventional boundaries of film discourse have essentially been obliterated. Necessitated partly by illness, but just as much part of his own creative impulses, Brakhage was creating more and more without actually shooting any film. 1995's "I Take These Truths" is a frenetic symphony of color--but it's not just paint that we are seeing on the screen. Brakhage is also scratching away the film emulsion and printing each frame twice, multiplying the layers of image to create effects that are both obvious and subliminal. At times, it looks kind of like the quickly passing graffiti as seen from the windows of a moving subway from a film set in 1980s New York. Other times it's like watching algae writhe under a microscope.

Not that the director abandoned the real world entirely. He creates his own version of "Wild Kingdom," going in as close as he could get to the garden and its creatures in "The Cat of the Worm's Green Realm" (1997). As the name suggests, the participants in this tale are a cat and a worm, and Brakhage's camera captures them amongst the foliage, with most of the film shot in extreme close-up, making that which is observed appear larger than life but also unreal, existing in a different space, unencumbered by the world outside of them. Made that same year, "Yggdrasill: Whose Roots are Stars in the Human Mind," combines the filmed with the hand-crafted to create a magical world that turns the everyday into the mythic. As in the second part of Visions in Meditation, there is an interplay between electricity, between neon and starlight and the visible ends of the spectrum, that is its own kind of mysticism.

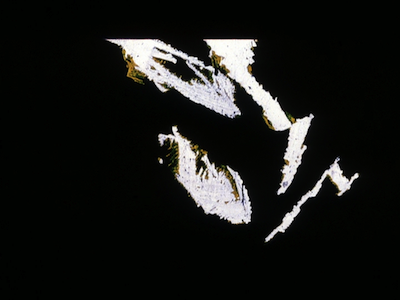

The final film on By Brakhage: An Anthology, Volume Two - Criterion Collection, and actually the last short Stan Brakhage made, was created by the artist scratching onto black film with his fingernail while he lay on his deathbed. "Chinese Series" (2003) was printed posthumously, and it's hard not to give it a morbid interpretation under the circumstances. The white and yellow scratches look like dancing bones--though they aren't sad or scary, but rather playful. In this, "Chinese Series" has something in common with 1998's "'...'" Reel Five." The fifth entry in the Ellipses series is a cycle of Jackson Pollack-esque splatters set to avant-garde music by James Tenney. The squiggles and squishes flit by at a jaunty pace, buoyed by the almost counterintuitive pacing of Tenney's piano.

What may be more striking about "'...'" Reel Five," though, is the openness of it. In between the jagged lines are big, empty white spaces. In "'...'" Reel Five," less is more. Anything can happen in those white frames. It's as if Brakhage has cleared the brush away, and he has given our imagination leave to run wild.

To be honest, I think I ultimately failed in my interaction with By Brakhage: An Anthology, Volume Two. In working my way through the Criterion set, I did not become engaged enough, did not find my own path to understand what Stan Brakhage was trying to do. More often than not, I found myself explicating his experimental shorts rather than actually interpreting them through my own intuition--it's more like I was appreciating them in the way I felt I was supposed to, not in any real one-on-one fashion. Still, by Stan Brakhage's own mission statement, that might be enough. That I took the time to look and to think at all is really the only thing he would ask of me as his viewer. His tiny pieces of cinema speak large in terms of technique and in establishing a theatre of ideas, and in honor of that alone, everyone should at least attempt to give his work a go, even if you walk away confounded and swear never to go back again. I'm not there yet, I'll keep trying, but it's up to you in the end. Either way, By Brakhage: An Anthology, Volume Two is Recommended.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

No comments:

Post a Comment