I last viewed--and wrote about--Merchant Ivory's 1992 masterpiece Howards End in 2005, when Criterion had first put it out on DVD and in honor of the death of Ismail Merchant, the film's producer. That old review is largely concerned with Merchant's passing and covers the excellent documentary that is a bonus feature on the double-disc set. At the time, it was part of the Merchant Ivory Collection, a sub-label of Criterion and not part of the collection proper; this 2010 reissue is a result of the film coming out on Blu-ray

Howards End is receiving this souped-up treatment because it won a public poll conducted through Amazon sometime last year. I forget now what other Blu-ray choices the movie was up against, but I do remember that it won hands down. Of all the Merchant Ivory films, this one has the most enduring popularity, and that's likely because Howards End best exemplifies what that pairing--named for Ismail Merchant and director James Ivory, who were not just creative partners but life partners, as well--does so exquisitely. Every time I watch Howards End, I am reminded of just how much fun it is. Merchant Ivory have been wrongfully saddled with this reputation that they are stuffy old Brits who have no idea how to loosen the corset and give us a laugh. Not true. They are more than aware of how absurd some of this drama is. Helena Bonham Carter's character in this movie, Helen, is insufferably dramatic for a reason. We're not meant to take her entirely seriously, she's too much of a spoiled brat not to poke a little fun at.

The title Howards End refers to a country estate that is the center of all the commotion in E.M. Forster's 1910 novel

The Schlegel girls are idly well-to-do, living on family money with their little brother Tibby (Adrian Ross Magenty). They are a soft parody of rich liberals with too much time on their hands, going to lectures about classical music and joining clubs in which the sole purpose is to talk about "important" ideas. They adopt any old cause that pulls at their heartstrings, including a down-in-the-mouth clerk named Leonard Bast (Samuel West). Leonard comes to their attention via a stolen umbrella and a jealous wife (played scrumptiously by Nicola Duffett). Leonard is a dreamer who studies astronomy and takes long walks because he read about a similar walk in a book. In truth, he's the perfect match for Helen, she's even read the same book, but he's betrothed to Jacky, despite his family being against it and her not having a thought in her voluptuous body (much less her head).

For as much satirical linework went into the film's portrait of the Schlegels, Leonard Bast is drawn with a much more serious eye. He is the reality of the film, and in a way its conscience--at least in terms of social class. He's aware of the divide between himself and the family who tries to help him, he understands that their notions of charity and self-improvement are luxuries that the real working class can't afford. It's easy to giggle at one of Helen's tantrums, until you see the horrible damage it can do to someone like Leonard.

As with many of the Merchant Ivory films, the screenplay for Howards End was written by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, who won an Oscar for this particular effort. Jhabvala has a keen sense of structure and has no trouble maintaining the balance of a multi-tiered story like Forster's. Her script forms its own perfectly ordered society. On one level are the Basts (lower class), on another the Schlegels (middle class), and on the top most, the Wilcoxes (upper class). Before she died, Ruth Wilcox wrote a note leaving Howards End to Margaret, a piece of paper that her husband Henry (Anthony Hopkins) and their children are quick to destroy. Even so, the very rich Henry Wilcox is surprisingly smitten by Margaret Schlegel, and after an unromantic courtship, he proposes to her. That proposal is also unromantic. "Would you like to let my London apartment? Or would you rather marry me and live here for free?"

Margaret is really the central character of Howards End. She is the one who grows up in the movie, even though she's already heading toward middle-age. Though Henry will ostensibly always be stuffy and greedy and Helen will always be flighty and self-indulgent, Margaret will learn to stop bending in order to please their moods and actually demand they start being more reasonable, changing herself and, to a degree, both of them. At the start of the picture, she is living carefree with her siblings, and they act rather adolescent, giggling at the expense of others and gossiping. Meeting Ruth gives Margaret a kind of role model to look up to (some even say she looks like Ruth), an example of what a more serious and grown-up life is like. Her engagement and eventual marriage to Henry ushers her over that threshold. As the true representative of the middle class, however, she must strike that balance Jhabvala has so meticulously laid out: she must bridge the gap. It's no wonder that Emma Thompson also won an Oscar. She's pitch perfect.

The plot of Howards End is dizzying and complex. Try to map it out. There are so many divergences and all these things circle back on themselves, and all of it works toward pushing everyone toward what, really, was predestined by Ruth at the start. The storytelling is so effortless, it's all told so matter of factly, you won't notice what a tangled mess of highways and byways it all is. In my review of Quartet, I wrote that I thought the key to James Ivory's directorial mastery is that he advances no significant style. He is as calm and mannered with his compositions as so many of his characters are with their feelings. One could say he even jokes about his own position amongst the proceedings, placing his director's credit over a shot of two maids working inside Howards End. He is here as a servant to the movie.

People always notice the gorgeous countryside around Howards End, photographed with a very wide lens by Tony Pierce-Roberts, but how come more isn't made of the marvelous re-creation of early-20th-century London? Look at the scene where Leonard chases Helen in the rain, or the one where he leaves Jacky to go to Howards End. We never know for sure what it is he plans to do there, just that he is looking for Helen. My guess is that he is resolved to leave his wife and take up with her. It's there in the slump of his walk, what was once the posture of defeat now being that of determination. But also look at the long city street he trods, of the detail on the building next to him, of the extras standing in the doorways. Getting the look of the country is easy, just find an open field and some trees; making current city streets look like long-gone city streets, that's where a director and his production department really come alive.

I wish James Ivory were working more. I assume the loss of his partner took much of the wind out of his sails. I'm happy to see he and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala and Anthony Hopkins have a movie coming out late next month called The City of Your Final Destination (hopefully not part of the Final Destination

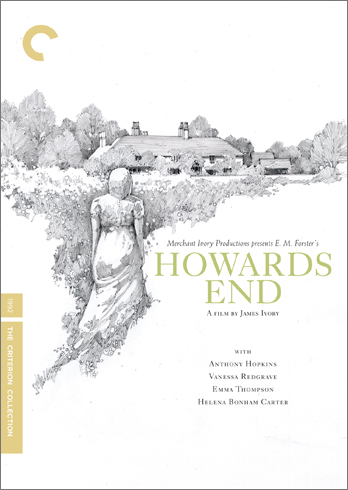

On a final side note, the old DVD of Howards End had a photo cover, this new one has a drawing by artist Andre Junget. It looks very much like an old paperback cover, like something I might find trolling the dusty aisles of a used bookstore. It inspired me to do a Google image search on E.M. Forster's novels, and I discovered that for the most part, they all featured some bucolic scene, nature isolated by the four corners of a book. Sometimes, such as this DVD cover, or this Penguin edition of A Room with a View, there is a lone figure that appears to be yearning to be a part of that nature. This article isn't about Forster exclusively, but scroll down for a couple of nice pieces from his books (and scan the other neat covers, as well). Though I didn't like Junget's illustration immediately, it does appear he did his homework. Looking at the artist's studio website, I find it contains a strange collection of precise, impersonal drawings designed for corporate use; in a weird way, that too seems spot on for Howards End.

This disc was provided by the Criterion Collection for purposes of review.

2 comments:

I read Howard's End many years before the movie came out. I hated the book, couldn't find a way into it. Only Merchant/Ivory were able to reveal it to me--they made the satire plain. It's such a great film.

Having said that, I have to fast forward now through the Leonard Bast parts. He's such a cringlingly humble victim.

It is a great film and I totally love it. But Merchant Ivory were definately not stuffy Brits. James Ivory was American, Ismael Merchant was Indian, educated in Britain, and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, their frequent collaborater was a German born Jew.

Post a Comment