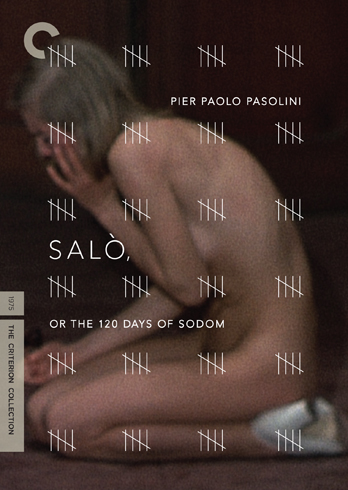

Once upon a time, Criterion spine #17 was the rarest of the collection*. The early release of Pier Paolo Pasolini's 1976 shocker Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom was the one of the first discs to go out of print for the label, disappearing not long after it had first been issued. Copies of the release sold for several hundred dollars on eBay, and fans created online guides to steer potential buyers through the murky waters of knock-offs and bootlegs.

When I was working on building a complete Criterion library some ten years ago, Salò was always the one that eluded me. Both the cost-prohibitive mark-up and the movie's scandalous reputation made me gun shy. Eventually, I bought a dubious Chinese facsimile so I could actually watch the thing. My hope was, if Salò was as off-putting as everyone said, viewing it would convince me that it was not something I needed to drop major coin on.

The theory panned out. One time through with Salò was enough for me. It was not a movie I ever felt the need to see again. I finally bought the legitimate reissue a couple of years ago, but I never even opened it. It was gathering dust on my shelf, still wrapped in plastic, when the Blu-Ray came through. I guess enough time had passed. I was finally going to watch Salò a second time after all...

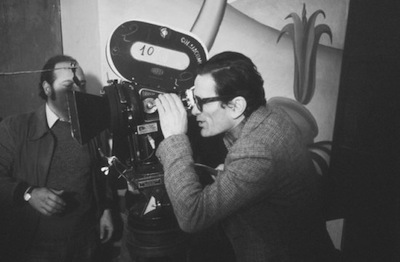

Pasolini's film in is an infamous slab of transgressive art. Inspired by the work of the Marquis de Sade, the controversial Italian director leveled his aim on his country's ruling class. Though set during the years during World War II when Italy was occupied and the Fascist government colluded with the Nazis, Salò takes place away from the combat, isolated to a sprawling, secluded villa owned by a shadowy collective of privileged dignitaries. These men have formed a secret pact, marrying each other's daughters as an old-school symbol of joint power. The four of them are intense libertines, and they have kidnapped nine teenage boys and nine teenage girls, all virgins, and taken them to this hidden house to engage in their every depraved fantasy. With them are adolescent thugs who act as their enforcers and aging prostitutes who stimulate the conversation by sharing the greatest hits of their illustrious careers satisfying the kinky fetishes of other powerful men. The men listen to these stories of indulgence and then indulge themselves with their captives.

Salò is essentially an escalating chain of humiliation and degradation. As the days wear on, the humiliations inflicted on the kidnapped adolescents gets worse and worse. Religion is banished, as is any display of emotion. If any of the prisoners break these rules, their names go into a little black book. When the excursion is over, the list of wrongdoers will receive a special punishment. Indeed, that perversion of justice is the climax of Salò, an orgy of torture, rape, and death. It's a bizarre concept to wrap your head around. These children have been violated, forced to eat human feces, and beaten, and yet in this upside-down mini society, they are the sinners. You'd think there was no penalty left, yet for Pasolini, no matter how cruel a human can be, there is always someone more cruel, always a deeper level of selfishness and evil that man can sink to.

It can be hard to judge button-pushing art, especially once some time has passed. What was shocking and meaningful in 1976 may not have the same impact or relevance in 2011. Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom still has the power to disgust. I retched more than once while watching it and frequently squinted or covered my eyes to obscure some of the more terrible depictions. So, I guess that is a win against the belief that we, as a filmgoing public, have been desensitized over the years by increased sex and violence in entertainment. Salò still has the power to make me sick.

On the other hand, it no longer has the power to shock. Maybe it's hard to compete in an age where we have something like The Human Centipede

Which isn't to say that Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom is without subtext. For as much as Pasolini is getting his jollies by creating this tableau of human indignity, he also is trying to make a point about the corrupt nature of governance and the true motivations behind fascism. Any will to power, his script suggests, is essentially selfish, no matter how much the would-be leaders crow about the greater good. In amongst the sex talk here, the abusers espouse theories about politics and human nature that seemingly explain and justify their actions. Pasolini undercuts their self-belief by demonstrating that these are just excuses they make in order to satisfy their own base urges. Unsurprisingly, the more harsh things get, survival tactics get more desperate. Prisoners turn on each other. Mankind is its own worst enemy.

Which is where I would guess Pasolini is really coming from. His contempt for the Fascists is equal to his contempt for the common man. Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom is the product of a severe misanthrope, one whom I suspect wants to get back at a populace that has misunderstood and persecuted him. He is serving us the cinematic meal he thinks we deserve in a way that is almost ironic: he decries cruelty and humiliation by beating up his audience using all the tactics his villains use. You will know what he means because he will make you experience it.

It's not a particularly complex response to a complicated world. Were Pasolini's filmmaking skills not so refined, I'm not sure we'd still be watching and debating Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom all these years later. It's a well-made movie even if I don't think it's a very good one. I know it has its defenders, and to be honest, I take no issue with that, just as I think Pasolini wouldn't take issue with my negative analysis. Salò is meant to be visceral, and so any visceral reaction on the part of the viewership means success. For my money, though, a better film would have moved me in a more profound manner. It would have still caused me to look away, but it would also inspire me to think about why I had done so. The deepest question I took away from Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom had nothing to do with narrative or thematic meaning; rather, I just kept wondering how you cast a movie like this. How do you go about finding actors who will read the script and say, "Oh, you want me to strip down to nothing, pretend to get sodomized, and sit in a barrel of excrement? Sounds like the role of a lifetime!"

Criterion has put the two-disc Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom package onto one Blu-Ray, packaged in a handsome cardboard box with a thick 80-page book featuring credits, chapter listings, photos, and a collection of seven different essays about the movie from filmmakers and critics. It seems to me that it's essential for a film of this nature to acknowledge the debate and give space to a variety of voices to discuss it, so I'm pleased that Criterion has done so both in this written format and on the disc itself. The essays in the booklet actually connect well to the 23-minute Fade to Black featurette that talks to Bernardo Bertolucci, Catherine Breillat, and others about their reaction to the film.

Pasolini himself gets his say in the 33-minute "Salò: Yesterday and Today documentary, which actually did serve to make me appreciate his vision more. He had clear intentions for what he wanted to do, even if some of those intentions are lost in the translation between artist and audience. We also get a look at the actual production in the 40-minute The End of "Salò," which gathers participants and crew members to discuss the working process and also the aftermath, including Pasolini's murder prior to the movie getting released. Amongst those interviewed are set designer Dante Ferreti, who also returns for a separate 12-minute interview. Also interviewed alone is film scholar and director Jean-Pierre Gorin (28 minutes), an aficionado of Pasolini and an appreciative viewer of Salò.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVD Talk.

* In terms of actual number of copies on the market, the very first pressing of The Seven Samurai may total less than Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, but given that the only change was the removal of a tiny restoration demonstration, I always considered the pursuit of that particular collectible to be the province of the overly fanatical.

1 comment:

"I just kept wondering how you cast a movie like this."

Exactly! The whole time I kept wondering what it was like on set, and how everyone reacted to it at the time. I agree with everything in your review. I am really liking your blog! Don't ever stop!

Post a Comment