I tried to watch By Brakhage: An Anthology, Volume One a couple of years ago, but didn't make it very far. A darkened room, a bottle of sake, and a bunch of silent, "experimental" shorts--well, it ended up being a Friday night of me sleeping in my chair.

This isn't a negative comment on the film library of Stan Brakhage, nor is it really a negative comment on me. It just is what it is. I simply had no real idea what I was signing up for. I don't know what I expected, but it was not grainy, disjointed, and let me stress silent short films. I tried to go in cold and open-minded, and it didn't work.

The video store near my house had Jim Shedden's documentary Brakhage

Stan Brakhage appeared on the art scene in the 1950s, at a time where traditional methods of expression were being dismantled in favor of something more personal. Perhaps it was a reaction against the conformity of the decade, perhaps it was an attempt to make a code so that the McCarthyites and other squares could not understand what was really happening. Maybe as a precursor to rock 'n' roll, the Beats and the avant-garde jazz musicians were pushing against the solid mass of post-War idealism. Into this, enter Brakhage and other new cinematic voices. Non-narrative, non-linear, their films are now called "psychodramas," and their intent was just as that sounds: a realization of the mind's abstractions, tales of the interior rather than the exterior. These were often surreal, without proper form, but one thing they were not prior to Brakhage was "first person." The filmmaker turned the camera from an outside observer looking at others to a single-person observer representing the filmmaker himself.

(Digression: I find the term "experimental" as applied to any artistic endeavor to be troublesome. As I interpret the notion of an experiment, particularly as it stems from scientific origins, is that an experiment entails putting two or more things together and seeing how they interact. The results are unpredictable, and they are what they are. There is no altering the outcome. In terms of cinema, there can be an element of randomness in what the camera captures, but the filmmaker is not beholden to the outcome. There is still choices to be made, and thus the material is manipulated. For instance, the artists chooses what to show, when to start and when to stop a shot, etc. If the final product goes beyond simply reporting the findings of the "experiment," is it still an experiment?)

There are twenty-six films on Criterion's two-disc first Anthology. The idea of reacting to each one film-by-film is daunting, to say the least. To interpret every short work here would require a particular critical rigor, especially since the films aren't really intended for traditional cinematic dissection. Stan Brakhage's shorts are meant to inspire a response that is often beyond articulation. The way he plays with light, the fleeting passing of images, is meant to leave an impression on the viewer and elicit a response that is often emotional, sometimes intellectual, but also somewhere beyond the ability of either to fully explain.

The set starts off easily enough. The first selection is 1954's "Desistfilm," the chronicle of a late-night party. It is one of the few movies in the collection to have sound, though the accompanying music is as dissonant in relation to the images as the images are in relation to one another. The camera here serves as a party guest, roaming the crowd, looking for someone to connect to but finding each of the other guests involved in their own thing. Given how inane some of the activity is, it quickly becomes obvious that this is likely staged rather than documentary. But if it weren't, which would be more self-indulgent: the action recorded or the act of recording (and exhibiting) said action?

It's a fair question, and one that certainly comes up watching the second film, 1959's "Wedlock House: An Intercourse." Brakhage records himself and his first wife, Jane, at home, moving in and out of shadow, catching small snippets of their lives together. The longer, more defined scenes involve them having sex, which is shown in graphic detail but projected in negative. Thus, the sex becomes otherworldly, almost as if we are seeing beings of living energy. (The Pander Bros. would achieve a similar effect in the 1990s with their infrared porno The Operation.) Yet, what are we to take away from Stan and Jane recording the minutia of their lives for all to see? Brakhage intended to meld life and art as one, but like reality television, is the act of living for the cameras something other than reality? (To be fair, much of these questions arose even before seeing "Wedlock House." In his Brakhage documentary, Jim Shedden shows pieces of autobio films made by Stan's friends and contemporaries that the subject wandered into, and the clips struck me as horribly self-involved. In the digital-video age especially, the act of turning a camera on oneself inspires the worst kind of narcissism. Hell, the whole internet age--the act of blogging!--has convinced us that our every brain wave is worth sharing. [For more of my thoughts on this subject, see my old piece on Jonathan Caouette's Tarnation.])

Not that Brakhage only kept the camera trained on himself and his loved ones. Though his film "Dog Star Man"* does show footage of the filmmaker and his pooch trudging through the snow in search of wood to chop, it also shows us many other things: landscapes both natural and man-made; the sun and the moon; the human body, both inside and out; water; babies; indistinct colors that shift like ink. Divided into five parts and clocking in at over an hour, "Dog Star Man" practically constitutes an epic in the Brakhage canon. Shot and edited between 1961 and 1964, the filmmaker plays with layers in this piece, overlapping his images so that two divergent tracks converge and melt together. He messes around with focus, movement, even readjusting the lens in mid-shot, stretching and distorting the captured object. His intention with all of his special effects was to replicate how we actually see things, how the eye moves as opposed to how a camera moves.

Similarly, his choice to forego audio was so that the viewer could provide his or her own soundtrack. Brakhage believed that the brain would create its own "music," as suggested by the tempo and arrangement of the imagery. If he provided music, it would create entirely different cues. Indeed, I admit to having cheated while watching "Dog Star Man". I thought Brian Eno's ultra-minimalist ambient piece Neroli

Stan's artistic intention is blatantly stated in the title of "The Act of Seeing With One's Own Eyes," the final part of Brakhage's famed Pittsburgh Trilogy. In this half-hour piece, Brakhage films in a Pennsylvania morgue, silently chronicling the bodies and autopsies. The absence of commentary does leave the viewer to only look, to absorb what is being shown, perhaps really looking at death in such gruesome and ghoulish detail for the first time in his or her life. It's strong stuff, and it closes out the first DVD in such a way that made me feel as if humanity could be and had been abstracted. This is life in all its detail. In all its absence of detail.

DVD 2 contains the bulk of the films in the anthology, and in addition to Brakhage's continued exploration of the filmed image, it also shows his shift into working without a camera at all. Brakhage's photographed shorts play out as living paintings, but in these other works, he approaches them as literal paintings. In some cases, he found ways to add paint and other substances to the movies through various means of construction; in other cases, he worked with the raw film itself, painting directly on the celluloid. "Mothlight" (1963) is one of his best known films, and it pioneered his abstract collage technique. In this case, he worked with a perforated tape to make a facsimile of film strips, and he put color and objects on them. When the resulting film prints were run through a projector, it created the illusion of movement and constructed images, including flapping insect wings. He used the same technique for his very short 1981 film "The Garden of Earthly Delights." In less than a minute and a half, Brakhage creates the sensation of being surrounded by foliage.

In 1972's "Eye Myth"--Brakhage's shortest piece, clocking at just 9 seconds--he paints around images of a man, and it alternately looks like the man is either being engulfed in the pigmentation or emerging from it. The same year, he used paint on a clear surface in front of the camera to create subtle changes over a landscape in "Wold's Shadow;" later, he'd paint on glass for other films, including 1994's "Black Ice."

"Dante's Quartet" from 1987 shows Brakhage burying faint images under gobs of color, making his own abstract versions of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven. For "I...Dreaming" a year later, his tools weren't so much paint, but text and music, applied with the same collage-like manner (it's one of the handful of selections with soundtracks). Text is also used in "Untitled (For Marilyn)," posing existential questions amidst a symphony of acidic blobs. Various shots of windows show them as more than gateways to seeing, but perhaps like the cliché goes, a stand-in for our eyes and thus visions of our souls; there is even a crying out to God.

In some cases, Brakhage moved away from the concrete footage entirely, working with color to create ever evolving paintings, like the wall in a modern art museum come to life or an artist's easel engaging in a ballet. "Nightmusic" is a series of interconnected images creating one continuous effect, whereas "Rage Net" continues the experiment further through altering the strips of film before laying down the paint, creating unexpected special effects. 1991's "Delicacies of Molten Horror Synapse" uses a violent rainbow of shading to recreate the effect of television on the eye, ultimately melting away to reveal the pattern lines of a TV screen itself.

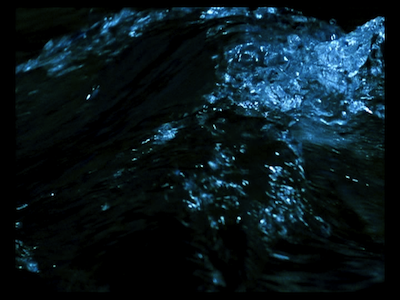

In the mid-'90s, Stan Brakhage was diagnosed with cancer of the bladder. In a case of poetic irony, one theory is that the paints and film elements he used were a cause of his illness. Unsurprisingly, his films started to examine his own mortality, and perhaps none so poignantly as one of the last films on By Brakhage: An Anthology, "Comingled Containers" (1997). The short subject is a collection of footage of water, shot in extreme close-up, sometimes so you can see the actual movement of the liquid, sometimes so that the bubbles and currents are right in the lens, appearing like glass jellyfish, storm clouds, and even in some instances like the blurry light of an x-ray. Water is the stuff of life, and like life, it can be contained yet never wholly imprisoned. Man is his body, but he is also something else. Imagination, spirit, essence--whatever you call it, it can't be held in our fragile frame.

From what I gather, this is a primary belief of Brakhage's. Much of his work is a testament to the freedom of the imagination. His lack of artistic boundaries, his expanding mode of expression, was his ultimate comment on life: what we can dream, we can see; what we can see, can be shown.

There is now also a second part to this series, and both parts are bundled together as Blu-Ray release

* Not to be confused with Suede's seminal album Dog Man Star

** Though eventually Eno's music was completely out of step with the frenetic editing in the latter parts of "Dog Star Man."

1 comment:

Hey Jamie,

I'm a big Brakhage fan, and I would have to say your interpretation of him (and the struggle that came with that interpretation) is pretty excellent. It's very fitting to his Modus Operandi. He wanted to push your/our perceptions. He wanted you to push your own as well. So by viewing this, you ultimately fulfilled his wish.

Great work man.

Post a Comment