Watching the Roberto Rossellini's War Trilogy boxed set doesn't feel like you're just watching movies, but like you are watching history. The history of cinema, to be sure, but also a bonafide historical document. The films contained herein--Rome Open City, Paisan, and Germany Year Zero--were made between 1945 and 1948. They were shot on location, documenting the ravages of World War II by setting the drama in the bombed-out ruins of Italy and Germany. Working with many non-professional actors, operating on a shoestring budget and often shooting with scraps of film, this is the birth of Italian Neorealism.

The stage is set with the 1963 introduction Rossellini filmed for French television, preparing audiences for the airing of Rome Open City. He talks about the hurdles of production and the intention of this effort. He was aiming for a sincere chronicle of what happened, to show the world what his countrymen had just experienced. It's hard not to think of the common reaction we could expect today, of audiences recoiling and shrieking, "No, it's too soon!" When did we become such ninnies, scared of the shadow of our own shared experiences? When Rossellini shot Rome Open City, the title had real significance: Rome was the only Italian city that had been liberated from Nazi occupiers. There he was, standing among the wreckage with his film camera, staring the moment right in the eye, refusing to flinch from the responsibility of telling others what happened. You can see the same thing in Iran when they protest, with citizens raising their cell phones aloft to record what is going down. Yet, in America, we get mad at journalists for telling too much and still can't figure out how to memorialize 9/11. Go figure.

Rome Open City (Roma città aperta - 1945; 103 minutes) is set in Rome during the latter days of the German occupation. There is a brief mention that U.S. forces may be on their way, but no one is sure if that is real or a myth. The story here, as written by Sergio Amidei with some assistance from Federico Fellini, is of the Italian resistance, of the regular people who did not want their country hijacked by Fascists and Nazis. They are the kindred spirits of the French Resistance, as celebrated by Jean-Pierre Melville and others, as well as the Germans who understood they were being dragged down by a madman, most recently immortalized in Bryan Singer's Valkyrie. These ramshackle citizen armies, to my mind, haven't had their stories told enough. As heroes, they are undersung. Rossellini himself would revisit the topic in his 1960 drama Escape by Night, which in a way is almost like a more Hollywood-influenced retelling of the picture that first got him noticed internationally.

In a way, the plot of Rome Open City can be boiled down to a central conflict of two men: the effete Major Bergman (Harry Feist), head of the Gestapo in Rome, and Giorigio Manfredi (Marcello Pagliero), an engineer who has become the focal point of the resistance movement. Bergman wants to get his hands on Manfredi, to torture the rebel and force him to reveal the plans and identities of his compatriots. Except to suggest this is a man-to-man fight would be to misread the situation in much the way Bergman misreads it. His enemy is not a single man, but an entire city and its populace, the people who refuse to lie down.

Aiding Manfredi in his flight is the noble priest Don Pietro (Aldo Fabrizi), the newspaper man Francesco (Francesco Grandjacquet), and Francesco's fiancé, Pina. She is played with fierce emotion by the amazing Anna Magnani, who is as much a force of nature as she is an actress. Pina is pregnant with Francesco's child, and also part of the movement, helping organize domestic revolts by gathering housewives for runs on bakeries and other businesses who they believe are hoarding or getting special treatment. The revolt is also generational. Pina's son from a former marriage, Marcello (Vito Annicchiarico), is part of a gang of boys who pull covert operations, blowing up gasoline tankers and the like, banding together on their own against the common enemy.

Rossellini and his writers build their movie out of all these pieces, carefully stacking them one on top of the other, but the structure never feels precarious. The narrative is told in a straightforward, linear fashion, and the unvarnished style--born of necessity, but it would come to define a movement--means they don't get in over their heads. There is little music, no overly fancy shots or stylized lighting; this is boots-on-the-ground filmmaking. There are moments of true beauty, where Rossellini and cinematographer Ubaldo Arata use the rundown environment for compositions with real depth and power, such as when the Gestapo storms Pina and Francesco's tenement and the action plays out on different floors in the building all at once. By contrast, the Gestapo's lavish headquarters are made to look unreal. These aren't invaders, they are imposters made to play dress-up. Rossellini's venom is palpable. For as deadly as he shows the Nazis to be, he also makes them comical. He laughs at them for being stupid, arrogant, and sick in the head.

Again, though, let's not make this sound overly simple. Rossellini is as unflinchingly critical of his own people where they deserve it. The rebels are ultimately brought down by Italians who don't care about anything but their own self-preservation. There are always rats, particularly when times are bad. The director also has no interest in whitewashing heroism. The good guys don't always win in the short run, even if there will be triumph in the long run. Men like Manfredi and Don Pietro show their true heroism in what they sacrifice, and though the ending of Rome Open City is grim, that gray pallor is offset by the determination in the faces of the younger generation, the ones who rebuild after the war. Defiance is more powerful than sadness.

The Americans finally arrive at the start of Paisan (1946; 126 minutes), and the movie's six vignettes track them from their landing in Sicily, through Rome and Florence, and ending up in the marshes of the Po Valley in the North. Long out of circulation, this fascinating anthology film is considered to be the real treasure of this box. Written by a team of screenwriters--Sergio Amidei, Klaus Mann, Federico Fellini, Marcello Pagliero, Alfred Hayes, and Roberto Rossellini--it looks at how the American soldiers and Italian citizens interacted with each other. The individual stories show the struggles with communication, the desire to understand, and the tragedies and sacrifices that would become commonplace.

The film begins with a squad of U.S. troops landing in Sicily, hot on the heels of the Germans. They get a local girl (Carmela Sazio) to guide them around mine fields in the area, and she is left in a seaside tower with Joe from New Jersey (Robert Van Loon), an earnest soldier whose yearning to get along might get them caught. Likewise, in the second chapter, another guy named Joe (Dots M. Johnson) learns a lesson in how bad off the Italian people can be. An African American MP assigned to Naples, he gets a little drunk and is taken around the city by one of a gang of street urchins. The kid (Alfonsino Pasca) ends up stealing Joe's shoes, but anger quickly turns to compassion when he sees where the kid comes from.

Not all the Americans are compassionate, though. Another drunkard, Fred (Gar Moore), misses a chance at love with Francesca (Maria Michi again) in Rome because he has gotten too complacent in his role as a hero, whereas an American nurse (Harriet Medin) rushes into danger in Florence because she is maybe too naïve about the consequences of war. Each of these stories ends on a dramatic moment, on the lesson learned or the last twist of the narrative knife. The technique reminds me of a lot of early American TV series, ones that told different stories every week, such as Naked City or Route 66, where a complete dramatic arc had to be contained in the specified timeframe. Rossellini doesn't really attempt to sew these together. Characters don't recur from chapter to chapter, and there is no hearkening back to any one driving element. Rather, these are marks along a map, the varied experiences of the men and women struggling to get out of a nightmare.

The final two chapters of Paisan are drastically different in terms of mood. The penultimate tale is set in a monastery in the Appenine Range, with real Franciscan monks portraying versions of themselves on screen, welcoming three army chaplains to stay with them. Though the setting is serene, the situation becomes uncomfortable when the monks learn that one of the Americans is a protestant and the other a Jewish rabbi, and they try to convince the catholic priest that they need to be converted. I am not sure if Rossellini intended them to come off as offensive and intolerant, that could just be my modern sensibility, since that is not the note the story ends on.

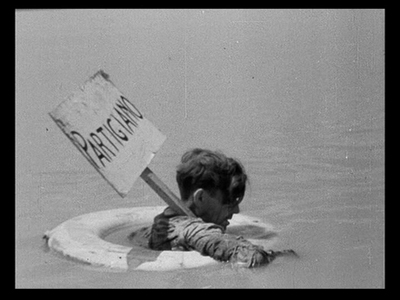

Far more grim is the final tale, with OSS agents teaming with Italian Partisans, fighting guerilla style on the river in the Po Valley. This remote outpost shows a war that is still very active and sparing few. It's a surprising finale for a film that was made after the end of the war. It strikes me as something one might expect to be made in the midst of a long conflict when there is no victory yet to celebrate. Rossellini the filmmaker, however, always wanted to show history as it was, he wasn't interested in making it seem happier or more convenient. By choosing to end Paisan on a downbeat, he also chooses to spotlight the sacrifice and pay special consideration to fighters whom the public record had not given enough attention to.

Paisan actually feels more slapped together than Rome Open City. It's not just the storytelling style, which in itself is sound, but overall, despite the grander scale of many of its locales, it comes off as the movie that maybe was made with less resources. This could be down to the places where Rossellini and cinematographer Otello Martelli took their camera. The scenes of poverty and the bustling crowds of the cities mix the filmmaker's fictional characters with real people, and once again, the director is also employing a lot of non-actors. Some of the Americans are awfully bad, even sounding like they don't really understand English that well (despite most of them being Americans). But that's part and parcel with the Neorealist style: authenticity trumps clichéd professionalism. In its way, it adds to the cumulative effect of the film. Just as there is no great narrative structure to tidy up the reality of war, there is no containing that chaos in terms of performance. This is life, flubbed speech and awkward moments included. A war may begin because of one act, and it may end with some guys signing a piece of paper somewhere, but within it, there are many trials, many failures and triumphs, and there is no meaning beyond living and dying.

Rossellini turns his camera to the country where so much of the misery of WWII originated for Germany Year Zero (Deutschland im Jahre Null - 1948; 73 minutes). Shooting in the rubble of Berlin, he examines the aftermath of the war as it pertains to one young boy. A 12-year-old whose grammar school years were spent in the Hitler Youth, he is now having to help his family get by, and the day-to-day on the streets is teaching him harsh lessons in morality and survival. While the choice to use a child for the focal point could have been a cheap ploy in the hands of another director, an easy way to get at our emotions, Rossellini, who wrote the film with Max Colpet, handles little Edmund with precision and care, molding him into a heartbreaking example of the effects of war and the trouble facing a populace being forced to start over.

Edmund is played by child actor Edmund Meschke (as you may have noticed, it was Rossellini's practice to sometimes give characters the same name as the actors playing them). The boy is effective in the role in a way only a kid can be. Much of the part demands that he be a blank slate. Edmund has not yet established his own identity, and so he is a follower. He has traded the Hitler Youth for a gang of Dickensian thieves and con men, led by a creepy sort-of Fagin, Edmund's old teacher (Erich Gühne). Edmund's family is worried that the boy has become corrupted, but they are ineffectual to stop it. We even learn that his sickly father (Ernst Pittschau) tried to keep him out of the Hitler Youth, having lost his older son, Karl-Heinz (Franz-Martin Krüger), to the army. Karl-Heinz has returned home, but he has been hiding in the family's tiny apartment, fearing punishment if he registers as a former soldier. Both of the older men being unable or refusing to work is what shifts the burden to Edmund, and thus necessity is a large part of his corruption. The need to survive can push us to terrible things. His older sister, Eva (Ingetraud Hinze), is also skirting the line. She flirts with foreign soldiers in bars to get cigarettes she can later trade for other things, yet she refuses to trade her womanhood to get even more.

Berlin was still in a horrible state when Rossellini took his crew there. The tenements where Edmund and his neighbors live are crumbling and hollowed out. Multiple families cram into tiny apartments; in Edmund's building, likely on the only floor that is habitable. The post-war government is dictating where people live, forcing the owners of the apartment, the horrible Rademaker family (led by the slimy Hans Sangen), to take in these ne'er-do-wells despite his protests. They literally have nowhere else to go, the society is now being compelled to take care of the infirm and the immigrants they might have once cast out. In Rossellini's hands, these unstable, near empty ruins become a metaphor for Germany's moral center. The ideology that had taken them over is in tatters. In one powerful scene, when Edmund is trying to sell a vinyl record of one of Hitler's speeches to some American soldiers, the dead Führer's speech predicting victory for the homeland sounds even more delusional and sad when played over images of the destruction.

The crux of the film is Edmund being faced with another wrong choice, and when he takes it, realizing that the people who have led him there have led him astray. It's a disastrous epiphany, because the boy is left with nothing. It's Edmund's year zero, a total reset, but the true shame of it all is that he doesn't have the tools to start over and rebuild.

I don't believe that Robert Rossellini thought that there was no hope left. I think he truly believed the German and Italian people would persevere. From what we can gather from what the director said about these films, his intention with the War Trilogy was to make sure that the people remembered. Moving on from what happened was useless unless we remember what happened, and so while much of what is portrayed in Roberto Rossellini's War Trilogy is bleak, it's not unnecessarily so. Also, given the faith that Rossellini had in the power of cinematic images, he likely knew that filmgoers would walk away with the more hopeful messages tucked away in their hearts. The resistance fighters in Rome Open City, the people offering aid to one another in Paisan, even Eva hanging on to her principles when it would be so much easier to do otherwise in Germany Year Zero--these positives dominate over the negatives. Granted, we have the benefit of history to know where it will all go, but we also have the knowledge that history does repeat, having seen that governments and their people can still go in the wrong direction. Some will always refuse to learn from past mistakes, and we can only cross our fingers that there will always be more people like Roberto Rossellini and those he portrays that will do everything they can to stop the bad guys from getting away with it.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

No comments:

Post a Comment