Alberto Lattuada's 1962 film Mafioso is one of the more delightful surprises of the last couple of years. This dark Italian comedy is the granddaddy of modern crime films like the Ben Kingsley vehicle You Kill Me or the Robert De Niro/Bill Murray picture Mad Dog and Glory

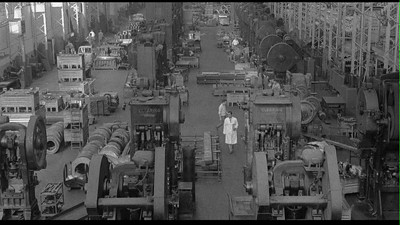

In Mafioso, Fellini-regular Alberto Sordi plays Nino, a middle-aged Sicilian who has made a career for himself as a factory supervisor in Milan. His job is to make sure that the men on the assembly lines run their machines with absolute precision. In the very first scene, he chastises one of his underlings for going too fast, for not pausing properly so that the holes he drills in a little metal plate are perfectly exact. Such details are important to Nino.

It has been quite a long time since Nino has visited his hometown. So long, in fact, that his family has never met his wife, Marta (Norma Bengeli), and their two daughters. Part of this is that Nino has been so devoted to his duty at the plant, he has not taken a vacation; another part of it is that he left Sicily under circumstances that are unclear, maybe even a bit shady. The first hint that something is amiss is when his boss, an émigré from New Jersey, asks Nino to deliver a special package to Don Vincenzo (Ugo Attansio), whose very name brings a hush whenever spoken.

Indeed, Nino's birthplace in Sicily is like a whole other world in comparison to mainland Italy. The difference between his curvy blonde wife and his moustachioed sister (Gabriella Conti) is immediately obvious, and then, of course, there is the vociferous welcome Nino receives, not just from his family but from seemingly everyone he's known since elementary school. Compared to the ordered, mechanical existence Nino lives in Milan, his Sicilian life is chaotic and pumped full of blood. There are also telltale signs of violence everywhere. A funeral is the first thing that Nino and his brood see when they arrive, and there are plaques outside many a doorway commemorating lost lives. Nino's father is missing a hand, apparently having raised it in opposition to violence and stopping a bullet with it. One of his old buddies is also spoken of as if dead, having betrayed men of honor. You might as well be dead if you go against your compatriots.

All of this seems completely counter to the gregarious persona Sordi portrays as Nino. He is boisterous, always positive, eager to see peace between his wife and his clan. Thus much of the comedy comes between the collision of happy, smiling Nino and the darker memory folks apparently have of him. On one side, they see him as successful and happy, his blonde wife being a curvy emblem of the good fortune he has had off of the island. They build sand castle women to look like her, never imagining they will meet a lady with such little body hair. On the other side, though, there is Don Vincenzo and his chilled-out emissary, Don Liborio (Carmelo Oliviero). Taking a trip down memory lane, Liborio buys Nino a hat like his cohorts wear and takes him to a boardwalk shooting game--where Nino manages to hit every target.

The serious precision with which Nino aims his gun hearkens back to his description of proper working methods back at the factory, and it also begins to show us what Nino, the happy husband and father, may have lurking in him. The idea that this man is a mafia killer is not just opposed to our first impressions of Nino, but it also plays against type for Sordi, who is usually the life of the party. Here he smiles big and talks with a booming voice, but there is nothing threatening about him. Yet, the switch between citizen and gangster is somehow natural, neither jarring nor harsh. It's like the old adage, "business never personal." Director Alberto Lattuada and his legion of scriptwriters make the switch in the story with just as much ease. There is a third act shift where Vincenzo and Liborio's interest in Nino is explained, and Mafioso takes a flight into all new territory that is tense and exciting. We end up seeing it long before Nino, and perhaps that's why we are less surprised, though I'd defy anyone to guess exactly what is going to go down.

One narrative trick I particularly appreciated in terms of setting up this transition is Marta's change of heart about Sicily. At first she hates it there, and Sicily hates her just as much. Eventually, though, she bonds with Nino's sister, teaching her the joys of body waxing, and apparently spends time with her father-in-law getting stories about Nino's childhood. That means when the subject of a hunting trip comes up, she's more than happy to encourage her husband to go, as she has heard what a crack shot she is. She may not know the full meaning of what she is pushing him into, but it doesn't matter, it makes him--and, by extension, us--more comfortable with it.

There is a vivaciousness to how Mafioso is shot that really brings Sicily and its populace to life. Even when working in somewhat unreal territory as Lattuada does here, the influence of Neorealism is never completely shed. Both the factory in Milan and the dusty streets of Sicily are shot in a documentarian fashion, with the man-made light of the metal works giving it the fake sheen of the city while the harsh sun of the country casts its brightness on life in the open. There is a subtle comment on class differences here, and even a comment on Sicily’s separateness in comparison to Italy as a whole.

This eye to realism likewise benefits Mafioso in its final scenes, as Lattuada doesn't push his character back into his old life as if it were really as simple as buying a new hat. Instead, Nino wrestles with some real issues, and what he is asked to do ends up having some profound consequences for his soul. Alberto Sordi is very good in these moments, letting a little bit of that early spark fade, and though his commitment to duty is reinforced in the tiny detail of his returning a pen he accidentally took from a co-worker before he left for vacation, the mechanical nature of it is now unavoidable. He now appears to be just another component of a machine he can't control rather than a man who keeps the factory humming. Mafioso predicts The Godfather by a decade, but even within it, there is a comment on how the Western world cannot understand what their brotherhood means. Don Liborio and Nino say as much early on, and there is definitely a vocabulary used here that would become pretty much cliché in future cinema; still, there is a gravitas to how they use the words that we won't hear again very often. It's as if Nino's fate is a warning, that this life has a consequence and that mythologizing it in popular entertainment will come with a price, as well.

No comments:

Post a Comment