Continuing its tradition of focusing on specific filmmakers at distinct points in their careers, Criterion's Eclipse Series has gathered together five films by Japanese provocateur Nagisa Oshima. Made between 1965 and 1968, Oshima's Outlaw Sixties is a profile of the controversial director as he broke away from the studio system in Japan and started making complex and daring narrative/anti-narrative films that explored taboo subjects and extreme reactions to modern life under his own umbrella. "Provocateur" is not a term I use lightly in this case, Oshima was part of a rebellious zeitgeist. Referred to early on as "the Japanese Godard," his cinematic explorations were of a similar mindset to the Nouvelle Vague crowd, and his independent spirit was in line with what John Cassavetes was doing in New York. Cinema was changing worldwide, and Nagisa Oshima was one of the flashpoints.

Oshima's Outlaw Sixties begins with the intriguingly titled Pleasures of the Flesh (1965; 91 minutes), the first film Oshima made via his own production company. He wrote and directed the feature, basing it off a novel by Futara Yamada. The movie contains some stylistic choices that would allow Oshima to tap into the popularity of the naughty "pink" genre (essentially, softcore shots of sex and a healthy dose of skin), but at its core, Pleasures of the Flesh is a potboiler, a strange crime film with a unique central concept. Katsuo Nakamura plays Atsushi, an obsessive man in his early 20s who has been pining after Shoko (Mariko Kaga), a young girl he once tutored. He has kept his distance from her ever since her parents persuaded him to kill a blackmailer who had molested Shoko as a child. He borrowed from the philosophy of Hitchcock and committed this crime on a train. It's good advice, and the murder was a near-perfect crime, except Atsushi was spotted by a small-time official who was about to be nabbed for embezzling public funds. He blackmails Atsushi into holding onto a third of the stolen money while he serves his full jail sentence. They have no connection, so the authorities will never know where to look for that portion of the missing cash.

At first, Atsushi dutifully does as he's told, but after Shoko marries another man and it becomes clear that he will never possess her, Atsushi decides to blow all the money. He has a year before the blackmailer will be out of prison, and if he burns through the ill-gotten gains by then, he will kill himself and avoid any further consequence.

What follows is a series of paid relationships, of Atsushi hiring prostitutes and desperate women to be his live-in mistresses. Most of the women are picked for their resemblance to Shoko, who haunts his mind like a ghost. The various arrangements peter out when other circumstances get in the way. One girl is a gangster's moll, another is married and trying to earn money for her family since her husband is unemployed. The freedom this money provides, and the schism between bought love and the real love Atsushi desires, makes him cruel. He grows bored with the prizes that are easily captured.

Oshima and cinematographer Akira Takada shot Pleasures of the Flesh for widescreen, with garish, fully rendered colors and often startling, abstract compositions. Some of the storytelling is experimental, and so in terms of narrative structure, the film is a little weak. The lock-step construction of your average crime film, where events lead one to another until often the crook falls under the weight of his own guilt, is absent here, replaced by a more breathless rush from one scenario to the next. It works for the large part, though the serial relationships grow a little tiresome before the final quarter of the film finally turns into its last plot twist. Atsushi becomes entangled in ironic coincidences, bringing about punishments he planned to avoid--though not in the ways he would have expected.

Oshima shifts into black-and-white for his 1966 film, Violence at Noon (99 minutes), a choice befitting its serious tone and its themes of duality. The movie is about a love triangle between two women and one man. The man is a thug named Eisuke (Kei Sato), who is also known as the High-Noon Attacker. His nickname was earned on a crime spree. He breaks into homes at midday and rapes the housewives he finds. On the day he is reunited with Shino (Sae Kawaguchi), invading the house where she is working as a maid, he escalates and kills her employer.

Shino and Eisuke come from the same village, and at one point were part of a collective raising pigs and chickens. In with them was the woman who became his wife, the teacher Matsuko (Akiko Koyama). A flood wiped out their livestock, and desperate measures were required. Shino sold herself to a local man of means (Rokko Toura) and ultimately entered into a suicide pact with him. When her own death didn't take, Eisuke took advantage. He rescued her from oblivion, only to force himself on her--a savior who looks for payback.

Both Shino and Matsuko are caught between their love for this horrible man and the fact that they know he is horrible. Throughout Violence at Noon, they run away from him but also run toward him. The script by Takseshi Tamura, from a story by Taijun Takeda, jumps back and forth in time to show how this killer wove a sensual web around the women. Oshima and Akira Takada use inventive camera techniques to reflect the multiple points of view and the fractured sense of self the women share. Extreme close-ups, fast zooms, whip pans, chopped-up scenes using repetition and quick cuts to turn action into collage--they all contribute to a feeling that these women are linked by a reality that has come off the sprockets. Only when they agree to their common ground do Shino and Matsuko find the courage to act. Some of the material about the two women being one, as well as the aesthetic methodology, reminded me of Ingmar Bergman's Persona

Violence at Noon can be a bit slow going at times, but its cinematic acrobatics show a more rigorous control on the story than Oshima displayed in Pleasures of the Flesh. There are none of the narrative gaps, none of the leaps that made that film stutter. The conflict between common sense and desire is already developing as a major theme in these first two films: we chase our passion even when we know it's not necessarily healthy to do so.

Clearly there was some cinematic back and forth going on between Japan and Europe during the 1960s. While Persona and Violence at Noon criss-crossed in their productions and likely didn't influence one another, the Godard tag that Oshima picked up earlier in his career has some real merit. The use of Shino's written letters in Violence is not dissimilar to Godard's use of title cards in his films. The French director is also known for his playful approach to audio, and I hear echoes of his technique in Oshima's soundtracks. Dropping out all sound for absolute silence, sudden bursts of incongruous music--these are JLG trademarks. The third film in Oshima's Outlaw Sixties, Sing a Song of Sex (1967; 103 minutes) begins with no sound. The camera is silently centered on a burn mark, and as the music comes in, so does the flame. (The use of audio in the opening scenes of the next film of the set, Japanese Summer, is even more dazzling.)

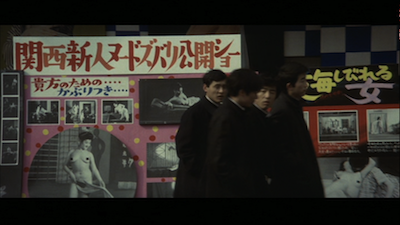

Sing a Song of Sex was a largely improvised film, and this "on the street" technique and its political posturing add more to the connection with the Nouvelle Vague. As the movie follows four restless, horny students over two days, Akira Takada's camera probes the scenes, rooting out the story. In one sequence, the camera is on a swivel, swinging back and forth between the bored and the drunk at a restaurant. In many others, it walks with its characters as they pass through the city. The use of advertising as a backdrop doesn't just evoke thoughts of Godard, but also Warhol and pop art.

In terms of story, Sing a Song of Sex is about a quartet of older students who are bored and restless as they talk about sex, go out drinking with their teacher and some of their female classmates, and deal with the intrusion of real life on their self-contained world. The movie is set during the return of a controversial nationalistic holiday, and the boys pass by protests without ever considering anything beyond their libido. Much of the film is spent searching for the elusive student #469 (Kazuko Tajima), a dreamgirl that only one of them has even seen, but for whom they all indulge a shared violent rape fantasy. Oshima is putting the political up against the personal and critiquing the disconnect of youth. His characters lack a moral center, and indeed, there is even a struggle to find the moral center of the nation. On one hand, you have the protest against the return of old-fashioned values, and on the other, you have kids looking to America, standing up against Vietnam and singing folk songs from the U.S. (Songs are seen as a method of communication that carries messages through changing history.) At the same time, Oshima brings up questions about Japan's Korean origins and the country's subsequent treatment of its neighbors.

Sing a Song of Sex goes on a little too long. (I had the same problem with all the films in Eclipse Series 21, actually, including as noted above; they kept going even after my interest in the initial concepts had worn out.) The final scenes bring the boys together with three women they have objectified or victimized and they are forced to prove whether they are all talk and daydreams or if they can make their sick fantasies actually happen. The staging is abstract and pedantic, much like later Godard or the pretentious soul searching of Bernardo Bertolucci's 1968 Partner

[Side note: There is an interesting comparison to be made between Sing a Song of Sex and Toshiyaki Toyada's 2001 juvenile delinquent film Blue Spring

Whatever wall of reality Oshima shattered at the end of Sing a Song of Sex (I prefer to think he went past the fourth wall and straight on into the fifth or sixth), it stays shattered for his 1967 film Japanese Summer: Double Suicide (99 minutes) (a.k.a. Night of the Killer). This black-and-white parable takes place mostly underground, in a basement prison where a roving gang is locking up abductees they hope to indoctrinate into their wanton cause. Our gateway into this No Exit

Both the death-obsessed teen and Nejiko represent Oshima's ongoing concern with the moral bankruptcy of bored youth. The old duo "sex and death" come up time and again in Japanese Summer, though Nejiko has a hard time finding anyone who will actually sleep with her. When she finally does, it isn't satisfying and nowhere close to life affirming. When the boy makes his first kills, he also finds it underwhelming. Give the kids what they want, and they realize they don't want it anymore. Nejiko's fate is tied to Otoko's regardless, and ultimately, they will discover that sex and death are tastes that are only great when they go together.

In the bunker, the sole link to the outside world is a TV set, one that is governed over by the pragmatist, earning him the nickname Television (played by Rokko Toura). The prisoners use the TV to monitor the progress of their captors and their gang war, but also to listen to the news about an American sniper that is killing Japanese citizens for no apparent reason. Oshima makes comparisons between this man and the assassination of John F. Kennedy, as well as between the political turmoil in his version of Japan and the race riots in the U.S. His heavily coded narrative weaves in and out of these real-world analogues, and presumably, each of his characters are meant to represent some piece of society. Some of the abducted are on the side of the killer, some want him dead, and even the ones who agree with each other can't actually agree to agree.

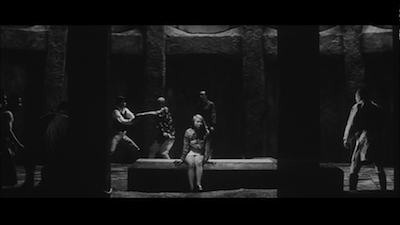

Japanese Summer: Double Suicide is obtuse by design, and Oshima provides no magic decoder ring to sort it all out. Some of his symbols are obvious (Nejiko and Otoko, for instance, are constantly framing themselves in outlines of bodies, like the chalk figures at murder scenes), and others are lost either to an historical/political context that I personally didn't understand or possibly are red herrings that only mean something to the director and his co-writers, Mamoru Sasaki and Takeshi Tamura. From the liner notes, I am led to believe that Oshima would be pleased that I was confounded by his movie; however, I am not sure how he'd feel about me being bored by it. Interestingly enough, for as abstract as the story is, the film itself is the most straightforward in terms of visual style. Japanese Summer is the first feature in the box to be shot by someone other than Akira Takada. New cinematographer Yasuhiro Yoshioka drops most of the experimentation and seems to favor more formal frame construction. The actors are usually arranged according to a very strict placement, calling to mind the look of classic paintings or still photographs.

I was disappointed to peek at the liner notes of Three Resurrected Drunkards (1968; 80 minutes) (a.k.a. Sinner in Paradise) midway through the movie and see that a Monkees comparison was already made for me, because I was totally ready to call that out. Opening with three guys walking arm and arm on a beach while a sped-up pop tune rattles along underneath, I couldn't help but think of the PreFab Five. Seeing the seemingly random comedic events that follow, the comparison stuck. Though, let's call it out: the Monkees' full-length Head

Three Resurrected Drunkards is like an angry art school comedy. Three new graduates--O-noppo, Chu-noppo, and Chibi, a.k.a. Big, Middle, and Tiny, a.k.a. actors Kazuhiko Kato, Osamu Kitayama, and Norihiko Hashida--go for a swim, only to have a mysterious hand come up out of the sand, take half their clothes, and replace them with other clothes and cash. Left with no choice but to put on the new outfits, O-noppo and Chibi are mistaken for two illegal Korean immigrants ("stowaways"), a soldier (Kei Sato) and his companion, who ran from South Korea rather than join U.S. troops in Vietnam. The Koreans try to kill the boys to cover their tracks, but the boys escape assassination only to be deported. They also get entangled with a Korean girl (Mako Midori) who helps them, despite having her own problems.

The odds are stacked against the trio, but Oshima gives them a Bunuel-esque out. Midway through the movie, Three Resurrected Drunkards resets, taking us back to the beginning. This time, though, the guys begin to alter events. Their main change: admitting they are Korean. This is a shift that was set-up by a faux-documentary digression where the actors take to the streets to interview people and challenge them as to how they define their national identity.

On paper, Three Resurrected Drunkards is a daring experiment in gonzo filmmaking; in practice, it's dated and makes for lethargic viewing. Were this really a Monkees jam, it would be a lot more manic and silly, and while that may not have been Oshima's intention, it might have been a little more palatable than the self-satisfied seriousness that is here instead. Everything seems too dialed down, including the more dramatic second half. O-noppo's crush on the girl, for instance, is too reserved, and so his anger when he sees how horrible her guardian (Fumio Watanabe) treats her doesn't have much impact. Oshima is building to a startling conclusion, one that drives home his anti-war message and boils with the anger he feels in regard to Vietnam and the historical mistreatment of Korea, but like most of the films in Oshima's Outlaw Sixties, it takes too long to get there, and the view along the way gets tiresome.

Look, I get why Nagisa Oshima is so well respected, and I also understand why the title of Oshima's Outlaw Sixties - Eclipse Series 21 is well earned. The Japanese film director was an outlaw. An independent filmmaker who broke from the studio system when it was clear he was not going to be able to make the volatile movies he wanted to make the way he wanted to make them, Oshima is a man with a mission. He is an artist with a passion for cinema, and his cinema is about the passion of individuals. Eclipse Series 21 showcases a selection of movies that are sensuous, aesthetically audacious, and for the 1960s, politically provocative. The five films in the box attack the foundations of moviemaking and dig down to its core, casting aside the rubble willy-nilly. For me, however, the more obtuse and disconnected the narratives became, the less interested I was as an audience member. This may make me an outsider, too, it's certainly not conventional critical wisdom, but I have to imagine that Oshima would respect my stance as much as I respect his. Your views on any of this, of course, will also be you own.

Trailers for: Sing a Song of Sex

Japanese Summer: Double Suicide

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

No comments:

Post a Comment