In the 1990s, when the original Rodney King trial went the wrong way despite what to most people was pretty compelling evidence, arguments were made about what we think we see versus what we actually saw. A video of a man being beaten, we were told, was not clear-cut. You see that club there? It's not actually connecting. And it's only one vantage point. You weren't there. How could you know?

Last year, there was a Hollywood movie actually called Vantage Point

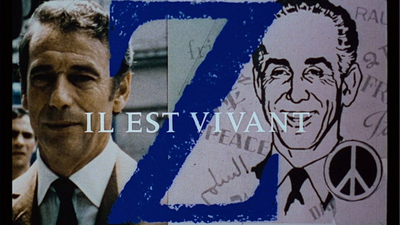

While that's not really the point of Costa-Gavras' 1969 political thriller Z, I was struck by how ahead of the curve he was in predicting how placing cameras in different places could show us the same event in different ways. Z is shot a lot like a documentary, an investigative procedural that has aesthetics in common with the Nouvelle Vague and the films of Francesco Rosi, and would in turn inspire Alan J. Pakula, David Fincher, and Steven Soderbergh. Z could almost be seen as a stylistic fulcrum on which the two sides of that equation balance, the link between Salvatore Giuliano and All the President's Men

Written by Costa-Gavras alongside Jorge Semprun and based on a book by Vassilis Vassilikos

The rally is far from peaceful. As the police stand by and watch, there are multiple skirmishes and attacks, the last of which leaves the deputy bleeding in the road. The culprits, Vago and Yago (Marcel Bozzufi and Renato Salvatori), are arrested and their story about being harmless drunk drivers perpetrating an unfortunate hit-and-run is accepted as fact whereas any counter theories are dismissed as Commie propaganda. Only after the deputy dies does an autopsy reveal that his skull fracture is more consistent with a clubbing than with an auto collision. A diligent prosecutor (Jean-Louis Trintignant) and a gutsy reporter (Jacques Perrin) start digging further, and pretty quickly, more inconsistencies in the story begin to show. Connections between Vago and Yago and a right-wing religious group further reveals connections between that group and the chief of police (Pierre Dux) and his right-hand thug (Julien Guiomar). Further attacks on witnesses only fuel the prosecution, as does government opposition.

Costa-Gavras takes us through the investigation step by step. He lines up each piece in their natural order, only taking minor detours into extraneous character stuff (Vago's sexual predilections; the deputy's heartbroken wife, played with stalwart grace by Irene Papas, and even glimpses of their marital strife). Working with renowned cinematographer Raoul Coutard, who shot the bulk of Godard's 1960s films (and who also shows up on the other side of the camera as a British surgeon), he shoots most of the action as if it were a documentary. Coutard's camera is rarely nailed down, but often moving with the flow of activity, acting more as a cold witness than an active part of the story. The fact that we can be everywhere at once creates a kind of hyper-naturalism. Z looks real, but it's not bound by time or space. Flashbacks are common, quick glimpses of memory, and even moments of minor comedy.

When the deputy is struck down, we see it clearly. The truck drives by, Vago leans out and hits the man, and the crowd parts to let them leave. Or is that what happened at all? I don't think that Costa-Gavras means us to really doubt what we saw the first time, but as we see the event as it is described by others, we see how the story of the drunk driving could appear plausible from their field of vision. It also keeps us on our toes, we're never quite sure of who knows what. Even one of the deputy's own people isn't positive the man got clubbed, and when he tells the story, we don't see the fatal blow. We do see the cruel hysteria of the crowd, snippets of the onlookers and enemies circling the victim playing backwards and forwards like we're flipping through snapshots. Costa-Gavras also drops out most of the audio, leaving only the elements the witness relates. It's cinema as point of view, as unreliable and incomplete as that can be. Watching Z, you can start to understand how one can argue about the veracity of a length of videotape.

As Z moves forward, it builds up a head of steam, and the investigation gathers its own momentum. Though the prosecutor doesn't make any grand speeches, he emerges as a heroic figure, committed to fairness and the truth. He is as distrusting of any one side as he is another. Trintignant plays him without any affectation. He's as straight a straight shooter as you're likely to get. On the other hand, there is nothing selfless about the reporter's pursuit of the story, the way he always secretly takes photos even when instructed not to and is aware of the monetary value of the information he's gathering. Perrin is loose limbed and energetic, jumping around and sometimes quite literally chasing the story. These guys are like the European version of Redford and Hoffman.

Interestingly enough, despite the successful exposure of the conspiracy, Z does not end on a hopeful note. Costa-Gavras gives the film a coda where things get worse instead of better. A news broadcast by Perrin informs us of the fate many of the players suffered, and a voiceover and text scroll details a government crackdown that follows, shifting Z out of amped-up Neorealism and into Orwellian sci-fi. It's a far more cynical way to close the movie than, say, Nixon being taken down (to continue the All the President's Men comparison). In this, too, Costa-Gavras is ahead of the game. In the decades that followed Nixon's souring of the American political system, we've often seen those members of his party who succeeded him use unsavory methods to take back the respect Tricky Dick lost them. It's much easier than earning it, and much more effective in demoralizing the public so they won't question the government's methods again. The ending of Z isn't science fiction at all; it's clairvoyant.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

Costa-Gavras

1 comment:

I really wish people would stop mentioning 'Vantage Point' and 'Rashomon' in the same articles (though I realize with this comment I'm doing the same thing).

Post a Comment