Before I started annoying cinephiles with my movie reviews, I cut my teeth in the late '90s writing music reviews. Music became an early obsession right around the same time I was discovering comics, and I've often pursued the former in the manner in which other fanatics have pursued the latter, chasing down B-sides and compilation tracks the way the biggest comics aficionados collect sequential issues, character appearance, and variant covers. The occasional soundtrack would appear with new mixes or specially recorded songs for the film by some of my favorite bands, and I'd have to get those, too. No surprise, really. Music and film have always had their own special relationship, with orchestration being used to add emotional weight to cinema as early as the silent era. The first sound pictures very quickly began showcasing song performances, beginning with Al Jolson, and over the years, the studios would find excuses for stars to sing even in non-musical productions in order to get a new hit on the radio, creating alternate promotional and revenue streams.

Then, of course, starting with the rock revolution in the 1950s and '60s, filmmakers began appropriating pop songs to use in their films, cutting scenes to the rhythm of a rock tune instead of a classical composition. I think most would bow to Martin Scorsese as the master of this. His use of the Rolling Stones and the Ronettes and many others would become so iconic, it would change how we would actually hear the songs from then on out. Scorsese has used one of the stars of today's DVD, Jimi Plays Monterey & Shake! Otis at Monterey, but surprisingly not the other (at least as far as I can dig up with a quick Google search; here is a cool Scorsese soundtrack resource). The director used Otis Redding performing "Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa-Fa (Sad Song)" in Casino

Of the music-related films in the Criterion Collection, my favorite is easily D.A. Pennebaker's Shake! Otis at Monterey, both for the sheer power of the performance and because, somehow, before I had seen it I was not an Otis fan. Which didn't mean I didn't like him, I just didn't know how much I liked him until this movie prompted me to go out and buy his greatest hits album

One of the greatest strengths of Otis' set in Shake! is sequencing. A downside of the digital age is that a lot of modern bands don't think about how to put an album together, they just toss a bunch of songs on the pile and listeners can put them together as they may. Same with live shows, where you can often just hear a band striking at particular rhyme patterns: fast one/slow one/fast one, or hit/new album/hit. Granted, Otis only had five songs and just under 20 minutes to do his thing, and his structure is simple--fast/fast/slow/fast/slow--but this is really precision bombing, hitting a tired and possibly skeptical festival crowd with the right kind of firepower at the right moments. Opening with "Shake!" got the crowd to its feet, "Respect" kept them dancing, and then "I've Been Loving You Too Long" took the fervor and excitement and started to tease and seduce, the music smoothing into a sensual, orgasmic purr. Then it was back up again, striking with a cover of a familiar number, "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction." Interesting that both of these African American acts chose to perform tunes by the most popular white rock groups, Otis taking on the Stones and Jimi working the Beatles' "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band" and several Bob Dylan numbers into his bluesy repertoire over the years.

Otis brings it all home with his final selection, his famous "Try a Little Tenderness." A number that builds from a slow, syrupy crawl, gaining momentum, working its way to a defiant crescendo, including a false stop and then a return mini-encore, the song is almost its own set, hitting the same tempos and feverish eruptions, the up and down and fast and slow, of the previous four songs all in one go. All the more disappointing, then, that Pennebaker makes his one and only mistake in Shake!, and what a crushing mistake it is! For more than 3/4 of the song, the filmmaker leaves Otis for the first time in the movie, instead choosing to create a montage of women at the festival, many of them sleeping and thus serving as a kind of visual pun to go with the lines about young girls getting weary. It's like going to a fireworks show and filming the ground, or going to a movie and sitting backwards in the theatre.

Why would you ever turn your camera away from Otis Redding? Despite being backed by some of the greatest musicians of the era, his Stax/Volt labelmates Booker T. & the MGs and the horn section the Mar-Keys, it's all Otis' show. The best performers of the soul era, including Marvin Gaye and Sam Cooke, managed to carry the crowd with personal charisma and the undeniable force of their voices. As a live singer, Otis is constantly moving, constantly smiling, and seemingly spontaneous while always being in full control of his band and of the arena. Were the "hit me again" moments in "I've Been Loving You Too Long" planned, or were they truly a moment of inspiration, where Otis just had to feel those musical punches a couple of more times? There is no way of knowing, but it sure looks spontaneous, just as the vocal runs he goes through in the final stage of the tune sound emotionally charged, raw, and totally from the heart. There isn't a moment in this film that you won't believe that Otis Redding is feeling every note he sings, and that's why it's impossible to forget Shake! once you've seen it.

There is a similar controlled spontaneity in the Hendrix set in Jimi Plays Monterey. The way his songs roll one into the other, from one of his own originals to a Bob Dylan tune to a cover of B.B. King, sounds unplanned, though I would imagine the real improvisation occurs within the songs, in the way Jimi and his band jam, and that the set is all laid out ahead of time.

I feel I must admit that I have never been much of a Hendrix fan. Too heavy, too fuzzy, that signature jammy quality just not being my style. That said, Jimi Plays Monterey still manages to impress. One doesn't have to be a fan of a particular musician to still appreciate what he does, and if you watch Jimi Plays Monterey and somehow fail to see how innovative Hendrix's style is and the talent and skill with which he attacks that guitar, I am not sure you can actually make a claim to understand rock music at all. Just consider the ways he tackles traditional songs like "Hey Joe" and Dylan's "Like a Rolling Stone" and then make a case for him not completely changing how rock musicians could approach the form.

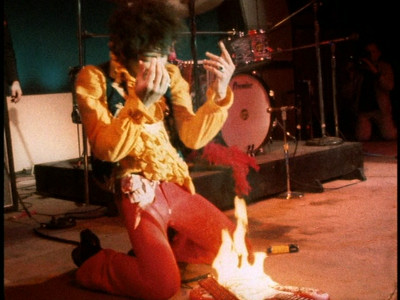

Pennabaker doesn't stay entirely in Monterey for this feature, instead setting a backdrop with information about who Jimi was, what lead to Monterey, and noting that this career high was followed a year later by the guitarist's death. (Coincidentally, Redding also died just a few months after these concerts, in December 1967, linking these two artists in another way.) Narrated by "Papa" John Phillips, one of the curators of the Monterey Pop Festival, we get a sense of who it is were are about to see, and we also get a glimpse of an earlier stage of the Jimi Hendrix Experience, playing that aforementioned Beatles cover and the Troggs' "Wild Thing" in footage from London. (In the case of "Wild Thing," we hear it again at Monterey, and the juxtaposition shows how far the Experience had taken the sound and their stage show in the time between.) We also see and hear other artists, including the Animals performing "Monterey," the tragic Rolling Stone Brian Jones introducing Jimi, and artist Denny Dent opening the film with a pop-art graffiti portrait of Hendrix, painting at hyper speed while Pennebaker lays "Can You See Me?" over the top.

Jimi is the real star, though, and Pennebaker smartly lets his set at Monterey run without interruption. His psychedelic point of view captures a certain vibe of the 1960s, and the fact that he and Otis could seemingly be so disparate, one more classical in approach and the other more visionary, and yet share the stage (and a DVD) so comfortably tells us something about the musical landscape of the times. These days, with everyone concerned about the brand, any meeting of R&B and rock (or, for that matter, hip hop and rock) is seen as novelty, even if most people's iPods have a little bit of everything, all genres represented. Maybe that's where the true festivals happen today, in the mixes we make ourselves. In that sense, I want mine to sound as good as this one.

No comments:

Post a Comment