So, it seems I am developing a bit of a theme here.

It occurred to me when I wrote my piece on My Man Godfrey [review] a couple of weeks ago that if I dug through all my reviews, I probably reference Sullivan's Travels more than any other movie. The message in Preston Sturges' script had a profound effect on me. He reminds us all that, whatever else our intentions, always entertain. That is the primary objective.

I considered making Sullivan's Travels my next choice, but then Modern Times [review] came in, and though the Chaplin picture postponed my taking my kajillionth look at Sturges, it actually added to the overall exploration that has distinguished the movies I've watched this November. Even better, the delay means Sullivan's Travels lands right when we're all preparing for Thanksgiving, and despite the big swamp of family dysfunction the holiday has come to signify for most of us, the adventures of one John L. Sullivan will remind us that maybe we really should take a moment to be thankful for what he have in these troubled times.

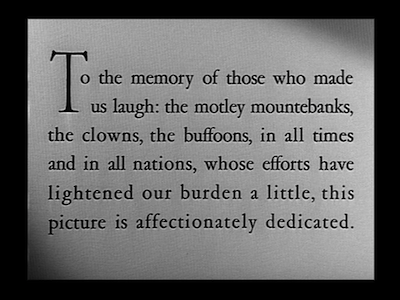

Sturges made Sullivan's Travels in 1941, when America was still recovering from the Great Depression and WWII wasn't yet our concern. (The film premiered in January of '42, and so was in the can well before Pearl Harbor.) This meant Hollywood had several years of wrestling with the modern condition, including a host of message pictures. (If only Sturges knew the kind of propaganda Tinsel Town had waiting right around the corner!) Apparently having had his fill of the self-importance of these movies, the writer/director decided to give his moviemaking peers the what for. So, he created the character of John L. Sullivan (played by Joel McCrea), a movie director known for light comedies like Ants in the Pants of 1939, but who wants to embiggen his image by making a serious movie about the American poor: O Brother, Where Art Thou?

Unsurprisingly, this isn't good news to the ears of the studio head. They'd rather their cash cow keep milking the teats that make them money. They taunt Sullivan for being raised a rich boy. How can a man who has never had to struggle possibly make a movie about struggle? It's a fair point that backfires: Sullivan decides to dress up as a tramp and go on the road, armed with only a single thin dime, and learn about life amongst the impoverished. Naturally, this is a worse idea than sinking their money into his serious artistic endeavors, but they are forced to go along with the plan. They try to send along a marketing crew, led by Sturges perennial William Demarest, to keep tabs on the golden boy, but Sullivan makes a deal with the publicity platoon to get 'em off his back. He also shrugs off his servants, including the haughty butler (Robert Greig) who dismantles his boss' desire to caricature the poor with the utmost of skill. Sullivan will not be deterred.

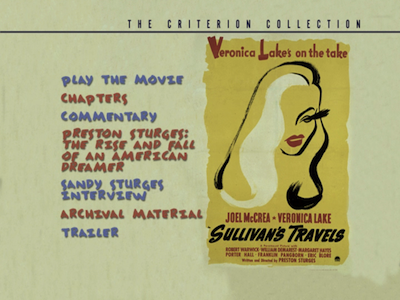

Except when he is. Over and over, too. For the first half of the movie, every road Sullivan takes out of Hollywood ends up taking him right back to where he started. On one such boomerang, he meets "the girl." I never realized we don't ever get a name for her, but she's played by Veronica Lake, so I will call her Veronica Lake. Veronica is on her way out of Hollywood, finally deciding her career as an actress isn't going to happen. Thinking Sullivan to be a bum, she buys him breakfast. When he asks how he can repay her, she asks if he can recommend her to Lubitsch. Oh, if she only knew!

Of course, she does find out eventually, and seeing that Sullivan is entirely helpless in the real world, Veronica insists on going along with him. She's a spunky beauty with a bit of a smart mouth, a perfect sparring partner for the wisecracking know-it-all. In fact, up until this point, Sullivan's Travels has mostly distinguished itself as a vehicle for Sturges' whipsmart dialogue; however, when Veronica learns Sullivan's secret, we also learn what a wily writer Preston Sturges is. He has spent this early part of the movie distracting us, making us think that for all his noble intentions, Sullivan will never burst out of his bubble and start to really see true poverty and strife.

The movie takes a sharp turn here. Sturges crafts an elegant montage that begins with Sullivan and the girl walking through a shantytown and ends with them finally losing their nerve when they are reduced to foraging for food in a garbage can. They've seen how real it can get, and they've had enough. Right there, without breaking his stride, Sturges has buried his message smack dab in the center of our good time. We were laughing at Sullivan, but suddenly we find ourselves feeling with him.

Sturges isn't done with us yet, though. His story has yet another turn to take. (Long before post-modernism, Sturges even had his character be conscious of the need for that twist. As a filmmaker, Sullivan is always aware of the structure of his own narrative, however accidental it may be.) On his last night out, Sullivan takes $1,000 in $5 bills and goes back to the streets to hand the money out to the poor and homeless. Being an optimistic man, but also a realist, Sturges sees the danger that Sullivan does not: a selfish hobo (Georges Renavent) hits Sullivan over the head and takes the money. Another turn of fate follows, and not only does everyone believe Sullivan was murdered, but he ends up on a chain gang to boot, unable to prove who he really is.

It's in this final twist that Sturges serves us with his real message. Having hit rock bottom, Sullivan's faith in himself and creativity is restored by the moving image. More precisely, by a Pluto cartoon. It turns out that on Sundays the gang boss takes his prisoners to the local African American church to watch movies with the congregation. I know some people bristle at the early slapstick scenes where the black cook is reduced to a racial stereotype, but one should consider the far more important and substantial image of the black preacher and his church. They open up their doors to the cast-off men of the chain gang, and the pastor reminds his group that they must not judge the criminals because everyone is equal before God. Think about what a powerful statement that is: here is a man who could not have been further marginalized by American society acting as the reminder that we aren't all so different from one another.

Sullivan doesn't hear any of this, though. His reminder is Pluto. As the cartoon plays on the screen in front of him, Sullivan is more interested in the reaction of the people around him. Everyone is laughing. It doesn't matter who they are, prisoner or guard, preacher or parishioner, white or black, they all forget their troubles and their differences and unite in the common bond of entertainment. There are no movies more important than the ones that transport people from their everyday lives. It's what the butler told him: poor folks don't care about seeing movies about living in poverty, they know exactly what that's like. Give them something that makes them feel good, and they'll turn out in droves.

The message of Sullivan's Travels isn't manipulative. There isn't a manipulative bone in Preston Sturges' body. That doesn't mean he doesn't lead us where he needs to go, but like My Man Godfrey and Modern Times, this movie informs our souls without ever alerting us to the fact that we're being taught a lesson. In his most important move yet, the final scenes of Sullivan's Travels, the character's rescue and redemption (this is a light comedy, you can't call that a spoiler) put this theory into practice. Think about how you feel at the end of Sullivan's Travels. Don't you feel good? Are you smiling? Didn't Preston Sturges prove his point?

Sullivan isn't wrong. The intention of any artistic endeavor, be it heavy or light, is to show us the life we didn't live. Fiction is meant to transport us, to show us a different point of view. With this movie, Preston Sturges is reminding his fellow entertainers to remember why they do what they do. He's also reminding his audience why it matters. We need to be like John L. Sullivan in that church and pause to take a look around, to really see what the world around us is like and empathize with the people we share it with. Otherwise, what's the point? Why even share the communal experience of going to the movies at all?

Even further, though, we need to empathize because though that fellow over there's problems may not be yours, it doesn't mean you can't have some understanding of them. Is there any personal divide so wide that we can't find a way to traverse it? If we watch a Charlie Chaplin or an Ernst Lubitsch film, we don't laugh as Republicans and Democrats, we just laugh. We should solve our problems in the same manner. Beyond rhetoric, we're just citizens trying to make our way. If one of us is going hungry or is hurting because he doesn't have health care or depressed because she can't love who she wants to love, then what good is it that any of us is satiated, healthy, or cared for. In the dark of the movie theater, we all laugh and cry the same, and so, too, should we go forth in life.

Happy Thanksgiving, one and all.

1 comment:

My favorite movie. One of the truly American greats.

It got a bit of a revival when the Coen's made "Oh Brother Where Art Thou?", the film Sullivan is planning in this movie.

Post a Comment