The provocatively titled Pigs, Pimps, and Prostitutes, the new 3 Films by Shohei Imamura boxed set from Criterion, is good on its promise and has all three of those things, and given that, the set could almost have the additional subtitle, "What's Not to Love?" Indeed, within its covers are three entertaining films that are also intellectually stimulating, comedically lurid, and masterfully crafted. Imamura, a seasoned professional who has made films as varied as the comically perverted The Pornographers and Warm Water Under a Red Bridge

The set opens with the 1961 feature Pigs and Battleships (108 minutes), a dark comedy mash-up about young love and the criminal lifestyle in post-War Japan. Set portside in Yokosuka, the squalid town rotates around the presence of American Navy men and their nearby station. The economy appears to be fueled by satisfying the pleasures of the occupiers, with the local men running gambling and protection rackets, as well as a healthy black market. Many of the women are part of the extensive prostitution business, entertaining sailors in dank backroom brothels and, if luck strikes, becoming high-paid exclusive mistresses.

Enter into this scene our young Romeo, a small-time hustler named Kinta (Hiroyuki Nagato). Kinta is in the gang of a yakuza underboss with perpetual stomach problems, and part of a criminal consortium moving into the pig farming business. This could be Kinta's ticket to the big time, with a fat bonus promised when the swine are sold; that, or if the cops find the body of a recently whacked chiseler, Kinta is expected to take the rap for the group as a less happy step toward his new position. A twitchy little dude, Kinta is ready to do what it takes to be a big gangster, whereas his girlfriend, Haruko (Jitsuko Yoshimura), wishes he would just chill out and run away with her, setting up a normal life somewhere else. This would rescue her from the family pressure to take a gig as a kept woman for one of the Americans, a sacrifice her mother and cousin would love her to make. She would do the work, they'd reap the rewards.

Imamura shot Pigs and Battleships on the vibrant streets of Yokosuka (and some very detailed, convincing sets), capturing a constantly active stream of people flowing through the alleys, guys like Kinta out on the pavement trying to lure drunken Americans into temptation. Lying somewhere between the inner-city slum pictures of old Hollywood and the more contemporary urban hustler flicks, Pigs and Battleships is, in a broad sense, the story of people doing what they have to do to survive. Imamura's political allegiance is understated to a degree, but not hard to figure out. The Americans are portrayed as pushy and lecherous, and the Japanese are all too quick to sell out. The gangsters prey on their own, attempts to buck the system or *gasp!* unionize are squashed, and prospects are dim. The alternatives that Haruko offers Kinta aren't all that appealing. Factory work? A restaurant? But hustling is much more fun! Hiroyuki Nagato is a charismatic actor, and Kinta's fumbling attempts at being the big shot are both endearing and frustrating. It's hard not to feel for Haruko, whom Jitsuko Yoshimura imbues with a clench-jawed independence. She is fierce in her desire, but she is blocked at every turn. By extension, we can surmise that perhaps Imamura has a similar frustration with his countrymen. I am sure Kinta wasn't outfitted in a jacket with the word "Japan" emblazoned across its back for nothing. These immoral, opportunistic men are the pigs, and they are turning Japan into their sty.

That jacket, and the rest of the more symbolic set-ups, are just the clothes the director and writer Hisashi Yamanouchi are dressing their plot in. At its center, Pigs and Battleships is a fun crime picture, with the hapless gangsters never quite getting it right. Discarded corpses wash back up at their doorsteps, they have practically bankrupted most of their cash cows (and those cows are getting restless), and they keep getting swindled when trying to secure feed for their hogs. Imamura underscores this with Toshiro Mayuzumi's score, which is often dramatically bombastic and regularly reminiscent of old Hollywood. Neither man is afraid to playfully hit those moviegoer buttons. They know what a well-placed upswell of horns and strings can do to the audience.

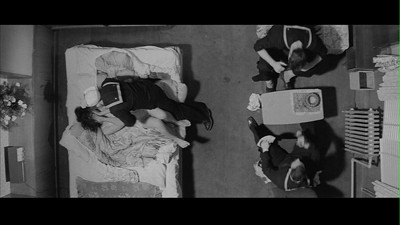

At the same time, while Imamura keeps his viewer comfortable by cradling him in the traditional, his film work is also incredibly innovative. Cinematographer Shinsaku Himeda's on-the-street shooting style brings to mind Godard's Breathless (Kinta is the goofball little brother to Belmondo), but Imamura is more daring than his French contemporaries when it comes to more rigorous breaks in formalism. Carefully manicured shots use camera movement to create a more emotional reaction. In particular, I am thinking of a scene where Haruko gets herself in trouble with three American Navy men. When it becomes clear that this is a situation that she cannot get out of, Imamura adds to the feeling of her being trapped by lifting his camera off the ground, peering down from a god's-eye point of view, and spinning the room on the screen, first this way, then that, before going into a dizzying whirl. There are many such moments in Pigs and Battleships, where the director wipes away the comedy to shove our faces into the more serious things that are at stake here. It's not all fun and games.

This technique of balancing the comic and the serious, the heavy and the light, seems to be inherent in most of Shohei Imamura's work, and it shows up again in the second film here, The Insect Woman (1963; 123 minutes), a biography of one woman, chronicling her descent into prostitution. Written by Imamura with Keiji Hasebe (Punishment Room, Temple of the Golden Pavilion), The Insect Woman once again juggles the funny with the tragic, with a little added sense of the grotesque mixed in for good measure.

Tome Matsuki (Sachiko Hidari) is born in 1918 into a sham marriage. The town slut (Sumie Sasaki) has tricked Chuji (Kazuo Kitamura), a none-too-bright peasant, into taking her as a wife, and two months later Tome is born. The film immediately jumps ahead a handful of years to show mom up to her old tricks again and the young Tome spying her in the barn with her lover. It's an important scene in the girl's life, and The Insect Woman is constructed of many such scenes. The script is really a string of vignettes, an outline of the life lived. Each shift in time or story is signaled by a freeze-frame, a title card indicating the date and voiceover featuring remembered dialogue or entries from Tome's diary punctuating the scene. These frozen moments can be wryly knowing or disappointing and sad, and sometimes all of that at once.

The Insect Woman traces Tome's development from her inappropriately close early relationship with her dad to a woman willing to stand up for herself (refusing to be kept by the landlord's son) but also showing a propensity to take a fall after swallowing a slick line (her manager at the factory beds her, convinces her to rally the workers into a labor union, and then throws her under the bus when he gets promoted). Her rape by the rejected son of the landowner produces a daughter, Nobuko (Jitsuko Yoshimura), whom Tome first leaves with grandpa during the war years as a temporary measure to make money in the next town over. Post-war, though, this stopgap measure turns into an extended journey in search of more work. This hunt leads her to religion, Imamura skewering modern selfishness by inventing a cult where one must only speak their sins out loud in order to have them forgiven. (How Catholic!) Willfully blind to reality, Tome makes herself the target of an enterprising madam (Tani Kitabayashi), who picks her up at the church and puts her to work in her "hotel." Only Tome eventually sells the madam down the river and takes over the business herself.

Imamura is using a delicate satirical thread here, sewing it through all of these phases of Tome's life and then bringing it around back to the start. Eventually, Tome becomes the kind of boss she despises, and by extension, her own mother. The girls she manages sell her out, and then her own daughter proves to be a cagier fox than the one that bore her. Without putting too fine a point on it, the director is connecting Tome's struggles, her moral compromises, and her eventual downfall, with the politics of the changing times. By the early 1960s, the get-what-you-can years of post-War occupation is giving way to a more independently minded Japan. The youth have no use for Tome's old ways, and even her daughter is scheming for a future working for herself rather than one selling herself (though, a little salesmanship is required to get seed money). Sachiko Hidari plays Tome at every age, effortlessly transitioning from a young girl wanting to do right by her father (while also sticking it to her selfish relatives) to an older woman seeking to only serve herself, to an even older woman who has been bilked, swindled, and abandoned, and insists she did all that she did for the good of others.

Again, her struggles can be funny, but they can also be pitiful and sad. There is something tragic in Tome's arc, but also something honorable. In the end, she doesn't give up. The final shot of her climbing a mountain mirrors the title card shot of a bug climbing up its own seemingly insurmountable hill. Is this evolution? A snapshot of the human condition? Feminism in Japan? One shoe covered in mud, one broken, but one must still imagine Sisyphus happy.

Some of the tell-tale aesthetic signs already apparent in the earlier movies don't take very long to show up in Intentions of Murder (1964; 153 minutes). The freeze frame returns, starting the picture with a montage of still photos, almost like we are looking at "before" images of a crime scene. Later, as the technique resurfaces, we get the same light touch in terms of music, as well as instances of meditative voiceover similar to that in The Insect Woman. The camerawork is also growing insistent again, with spins like the ones in Pigs and Battleships and amazing tracking shots, including following a young boy in the market, working on three levels as his mother flees and tugs him along, the boy looking back at the man that pursues them.

Which kind of makes it sound like a Hitchcockian thriller or something, which it most certainly is not--though there is a similar macabre sense of humor, a fascination with the secrecy and movement of trains, an interest in voyeurism, and the repeated use of reflective surfaces as tools for characters to peer into their own psychosis (most memorably, the bottom of an iron). An Imamura heroine is different than a Hitchcock heroine, however, and so whatever the psychosis, far removed from a Hitch ice princess. Sadako (Masumi Harukawa) is plump and dowdy, the shy sort-of wife to Riichi Takahashi (Ko Nishimura). Sent to his family to be their maid, working off an old ancestral debt, Sadako is in the clutches of a man who, like many an Imamura villain before him, has a rather loose definition of what constitutes a household chore, and Riichi takes his liberties with the young girl. For the superstitious, and as revealed in scenes containing shades of the witch segments of Macbeth), this hex is a continuation of a curse that has lingered over the Takahashi household since Sadako's grandmother, the mistress of Riichi's grandfather, decided she would be second best to no one. Ancient mistakes are repeated, and all the male descendents are of poor health. Riichi has a persistent cough, and the son he had with Sadako, Masaru (Toshihiko Hino), is frail and...well, not an illness, but he's also petulant.

Sadako has quietly accepted her life as Riichi's glorified servant, including not rocking the boat about their lack of a marriage. Things change, though, when an intruder (Shigeru Tsuyuguchi) breaks into the house when Sadako is alone, and instead of robbing the place and going, rapes her. An odd fellow, he first rolls over and cries before tossing money at his victim and warning her not to tell anyone. Though this troubles Sadako, she thinks she can get through the pain and the shame, but when her attacker keeps showing up and eventually starts to profess his love, this gets harder and harder to do.

The men don't get off all that easily in any of these movies, but Intentions of Murder seems particularly disgusted with that side of the human species. Once again written by Imamura and Hasebe, from a story by Shinji Fujiwara (A Colt is My Passport and Blackmail Is My Life

Besides being a thief and a rapist, Sadako's attacker has a variety of other problems. The lowlife works at nights playing drums in a strip club, blaming such a demeaning job on the fatal heart condition that he is trying to inject with enough life to take a last shot at romance. It's a rather on-the-nose ailment, the would-be Don Juan with a heart that doesn't work right. He's got mommy issues, as well, crying his heart out to Sadako about his mom the hooker who never loved him. Clearly, both of these men want to take the maternal tenderness they always felt denied them, even if by force. In the same way that Riichi's mistress drifts to him because she sees a man she can push around, so too do these men gravitate to Sadako for the mother she could be. (Compare this to Tome in The Insect Woman, who also has infantile men vying to suckle at her breast, and whose main later-in-life relationship comes with "mama/papa" nicknames.)

The only problem is that Sadako already has a boy that she really is mother to, and the overall arc of her character is to accept her rightful role as his primary caregiver, which includes the very real action of having the Takahashi family registry changed to reflect that she is his birth mother. All of the actions she takes in the movie--the consideration of suicide, the possible flight to Tokyo, the murder plot against the intruder--are steps toward Sadako's independence. In a way, Intentions of Murder resembles a battered-woman-escapes-type drama, what with the way Sadako has been hoarding money to buy her freedom and the acts of desperation that almost derail that. Imamura has better things in mind for the girl than a violent showdown with her abuser, however; he'd rather she grow into her own for real.

All of this is unfurled with the same deft and teasing hand as we've come to expect from the director in the first two films in Pigs, Pimps, and Prostitutes: 3 Films by Shohei Imamura, except with an even more assured sophistication. Imamura never telegraphs his next move, but always keeps the viewer guessing. Though he shares some of Sadako's inner thoughts with us, they aren't there to explain further than the small moments they illuminate. Visually, he alternates his compositional framing, sometimes using an elaborate depth of field and the aforementioned reflective surfaces to show the many layers of Sadako's entrapment; these are knowingly juxtaposed with the more open scenes, including the rapist's rooftop confessions where Sadako tries to pay for her release or the landscape that surrounds a receding train, the lone woman standing at the back and watching us as she leaves. Intentions of Murder is definitely the heaviest of the films here, though not without its humor, usually throwing sharp elbows at the characters that would do its heroine wrong. The laughter makes the rest bearable, giving enough to carry the audience long enough for the girl to pick herself up and declare she's a woman.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

1 comment:

LOVE this review of Pigs and Battleships! I haven't seen the other 2 yet but this well-written piece makes me want to. Great job!!

Post a Comment