There was no movie in 2008 that I anticipated more than The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. A long gestating project, it had several formidable building blocks that really hit the right spot for me. By the time it came along, I risked drowning in my own excitement, though at least I was able to see it ahead of some of the hype. One perk of reviewing movies is that you get to see them a little earlier, often before the promotion reaches critical mass and threatens to swallow the movie whole. Had I had to wait a few more days, maybe the scales would have tipped; maybe the chatter would have combined with my already epic wishes, and the image I had of the final result would have been insurmountable, regardless of the quality of the movie.

Luckily, that did not happen, and I was as pleased by Benjamin Button as I could ever have hoped to be. At the time, I reviewed it for DVD Talk, and though I gushed, I felt the movie inspired me to write a pretty good piece detailing how the movie spoke to me, how it appealed to the F. Scott Fitzgerald fanboy inside of me. This was written the night of the screening, before it would become hip to dislike Benjamin Button, and the review would become one of my most read pieces (currently #2 in terms of my personal hits on DVD Talk). When I voted in Film Comment's readers poll (I have long since sworn off a critic's top 10 of my own; too many fleas on that dog already), I put it at the top of the list with Wall*E

Often, if I review something theatrically and then revisit it on DVD, I will write a fresh review from scratch, giving my second-time-around impressions, without going back to the original review. On rare occasions, when I feel my initial reactions are as good as anything I could say a second time, I stick to the first piece. Which isn't to say I didn't take anything more out of the repeat viewing, just that my thoughts were crystal enough or my prose good enough that I am not yet ready to get around to the other side. This time, I will combine a little of both, and I will begin by reprinting my original piece on The Curious Case of Benjamin Button before sharing further ruminations immediately after:

* * * *

F. Scott Fitzgerald is my favorite author. His prose has a wonderful lyricism that shows a real knack for capturing the beauty in the simplest of moments. The way he composes a line can delight in its construction while breaking your heart with its vocabulary. His stories have an outer glitz that serves as a mask to the dark romanticism behind it. He always showed his readers the diamond first, and then the price it cost a man's soul second.

I don't think I've ever seen a film adaptation of Fitzgerald's that has captured that ephemeral quality of his prose--that is, not until I had seen The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. Ironically, the film that pulled off this feat is the one that has the least to do with the actual source material. Outside of the title and the basic concept of a man born old and aging backwards, ending his life as a baby, the film of Benjamin Button takes virtually nothing from Fitzgerald's short story. It does, however, draw on the author's complete works in theme and tone, tackling notions of doomed romance, reinvention, and indulging in the full flavor of life. Hell, even the scenes of drunkenness feel like they could be pulled from any number of Fitzgerald's jazz age stories--or even from his biography.

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button was adapted by writer Eric Roth (The Good Shepherd, Munich

Benjamin's story encompasses the whole of the 20th century. Born on the day World War I ended, we watch Benjamin travel through the Depression, WWII, and even Beatlemania and the 1980s. This is no Forrest Gump

Despite technically being the same age, when Benjamin and Daisy first meet, he is an old man and she is a little girl. Through the years, as their respective ages travel toward a common middle, the pair goes through many reunions, false starts, and misunderstandings before Benjamin finally becomes the man he wants to be and the lovers join at last. Anyone who has read The Great Gatsby

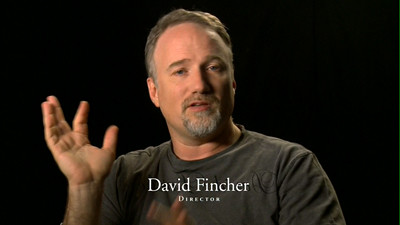

Apparently The Curious Case of Benjamin Button has been in development for nearly fifteen years. (Turns out we were spared a Ron Howard version starring John Travolta; thank God!) I imagine one of the biggest challenges was how to deal with the aging factor. Not only do we need to see old man Benjamin with a wrinkled body proportional in size to a newborn and a young child, but we also have to see him at the various ages of a full-grown man. Likewise, we have to see Daisy getting older while he gets younger. Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett are required to play both above and below their respective ages, and with the help of make-up and what I assume are some imperceptible digital effects, David Fincher has pulled it off remarkably. Though it's hard to pin them down in the ill-defined years of their 30s and 40s, when the two actors should look most like themselves, the transformation is still rather seamless. Credit is also due to both of the actors, who don't let the make-up do all the work, but who expertly walk in the shoes of different eras while maintaining the core of who they are.

It's not the only visual feat that Fincher pulls off, either. From recreating Depression-era New Orleans to the oceanic battles of World War II and 1950s Paris, the director paints across the screen like a vast canvas. A sunset witnessed by Benjamin and his ailing father (Jason Flemyng) is a gorgeous portrait of light and shadow, of water vs. sky. Equally stunning are images of burning battleships or a dancing Daisy silhouetted in night and fog. It's in these moments that Fincher captures the feeling of Fitzgerald's prose, his pictures evoking the words the way Fitzgerald's words so vividly created pictures. Similarly, the way the director uses classic film styles to reference the memories of characters in the story, including a running gag involving a man being struck by lightning, effectively simulates how Fitzgerald characters might remember times gone by through songs they loved or books they read.

At nearly three hours, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button is as rich as any thick novel covering the full scope of a man's life. (By comparison, Fitzgerald did the same in a much shorter space. The short story "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button" runs twenty-two pages in my The Short Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald

If The Curious Case of Benjamin Button isn't the best film of 2008, it's very near the top. When it comes time for my biography to be told, I can only hope that I would have spent my time as well as this fictional character, and I can only dare to dream that it might be executed with as much grace and depth as David Fincher has achieved here. An existence well lived, a story well told--surely there is nothing greater than that.

* * * *

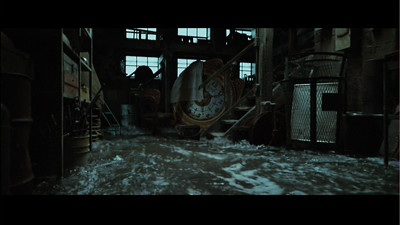

Reading over my review again, I don't feel my interpretation or understanding of the movie has changed, but I do think it has deepened. My first reaction on watching Benjamin Button a second time was how dark the movie is. Death is a constant in Benjamin's story, its grim pallor coloring everything (and note how darkly lit many of the scenes are, even in the pictures here). It begins with the irony of the infant starting life at an old folk's home, learning to accept death as both natural and common. It should be coming for him, it is a byproduct of his condition, but whatever spell has been cast on him has changed how death holds an individual. I guess this morbid theme should have been more obvious to me, as what I thought was an astute observation turned into a "Well, duh" situation the moment I started watching the extensive and fascinating documentary feature on the second disc of this Criterion set. The very first clip is of David Fincher talking about losing his father to cancer and the way his grappling with that became a part of the filming of the movie.

Benjamin's place in the world may have a feel-good "live every moment" lesson at its core, but there is a decidedly more pronounced intelligence than one might find in your standard second-chance post-tragedy picture. The message here is to live every moment, but accept the role age and wisdom plays in each one. If youth is wasted on the young, then don't toss away important things when you're not in a place to understand them fully. Patience is a virtue.

This is most evident in the love story, which is antithetical to the standard tales of young love that is the passionate energy of most romantic movies. Daisy offers herself to Benjamin, but he refuses her advance because it's not right yet, a rebuke she carries with her in a tight little fist in her heart, and that only likely makes sense to her years later when, while convalescing after an accident, she rejects Benjamin, choosing instead to wait until she is herself again. Benjamin wanted her to be strong enough and wise enough to love him with more than an impulsive schoolgirl lust; this carries over into her wanting to love him only when she can be her own self-sufficient person.

Meeting in the middle is less about being physically compatible, but more about being mentally compatible. Like wine, let this romance ferment. The risk, of course, is that they will grow apart, and thought it's a risk all lovers must take, for them it is a fait accompli. As Benjamin was able to be a young man learning from the old, however, Daisy will have the reverse position, being able to learn from him as he grows young. Both are taught to savor the things that matter by seeing the way others are losing their grip on those things. In Daisy's case, it must be more bittersweet for bringing her experience as a mother to taking care of Benjamin as his life ebbs. He is just a baby when he passes, having forgotten all he learned, the complete opposite to the baby daughter Daisy raised, whose every day was a new experience.

It's not a romantic ending, certainly not in terms of their relationship. Benjamin didn't really have mother issues; if he was seeking a mother surrogate to replace Queenie, he didn't realize it. If that was his reason for connecting with Daisy, it was a primal instinct, an act of self-preservation. The saddest scene in the movie is not a physical death, but an emotional one. It's when Benjamin, now in his early 20s, has come to see a middle-aged Daisy one last time, and she ends up going to his hotel room. The compulsion, as one might read it on Cate Blanchett's face, is to feel the passion again, to see if it's still there; the disappointment, again conveyed largely through expression and body language by Blanchett, is that it's not. The romance has died.

Or again, just matured, transmuted to something else, love of a different bloom. This is really the meaning in the much-maligned metaphor of the hummingbird, which possibly chafes some reviewers because its function is more literary than cinematic, the visual maybe needing a prose back-up to convey its full power. It's not that everything is connected, but that all life is transformative, continuous, the energy goes on. If Captain Mike (Jared Harris) has become a hummingbird after dying in the U-Boat attack, then it's a moment out of Ovid

When you boil it down, all of Benjamin's encounters and re-encounters involve stories. Everyone has their own, and Benjamin is the catalyst for each person telling it. In some cases, he is the reason they finish the narrative, such as Tilda Swinton's character finally returning to swim the English Channel (as it were, defying the flood rather than succumbing). Daisy is sharing the tale with her daughter--and truly sharing, the daughter reading it aloud to soothe her dying mother while also taking it into herself. Even when the story can't always be trusted, such as the mixed-up memories of the residents of Queenie's old folks home, they are still part of the mythology. More often than not, those stories are full of hurt and sharing them is part of overcoming; life is all about mourning, the grieving process for what could not be and what we know will come. I think one missed opportunity here was that the man who was always getting hit by lightning should have told eight or nine different versions of the strikes while still claiming to have only been hit seven times. The point being that it would be no less true, not as long as it's true to him. Queenie believed the faith healer helped Benjamin to walk, and that brought her comfort. Nick Carraway felt the same of Jay Gatsby--he is the man he said he was, and thus better than the whole damn lot of them.

You will believe, through the magic of moviemaking, that a man can be born old and die young.

Because then, wouldn't we also have the go-ahead to question the veracity of Benjamin's own story, the diary being read aloud and forming the movie? It, too, could be invention. It's all invention, really. A child aging backwards, a hummingbird in a war zone, seven bolts of lightning. Taking a hold of the story could give one the power to command it, to take over life's quirks and coincidences. Isn't that the point of the story of Daisy's accident, told in an expertly paced, rapid mis-en-scene by Fincher, to say if just one piece could be rearranged, then death could be cheated further?

Which brings me back to story again: you can't die if your narrative is preserved between the covers of a book or on a two-disc DVD set. Watching the talking heads sharing the production tales on disc two definitely gives one some fulfillment in terms of a need for preservation: we were here, we did the work, here is how that happened. The fact that they approached their movie storytelling in such a classic, tried-and-true manner is like the gift they give to us, returning us to what's important about shared experience. The future meets the past, technology enables tradition. Fincher embraces old cinematic and literary styles and integrates them in with his new way of doing things.

When I first saw The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, I saw it with one of my favorite friends and my most ardent collaborator, and by chance, we both rewatched the movie on the same night, too. When we saw each other the next day, we discussed our new impressions, and she mentioned the scene where Benjamin and his father are talking, before Benjamin knows that he is a Button, and the son tells the father that old age isn't so bad, it's nothing to fear, its routine is not crushing. In fact, in narration earlier, he notes that the routine is liberating, clearing the way for the mind to sit and ponder other things (how very Zen!). In the end, it is the simplest truth of all: if you can get through that, you can get through this. If you can survive the teen years and the perils of adult life, you can survive a well-earned retirement. If you can grow up, you can grow old.

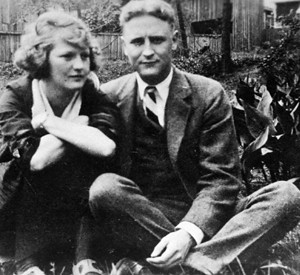

Scott & Zelda Fitzgerald

1 comment:

my impression was that the hummingbird symbolized the beauty and delicate fragility of life that can be taken quickly and unexpectedly, as in when so many lives were taken in hurricane katrina. so the lesson is to savor life- appreciate it for its delicate beauty fragility and short duration. i went through my mother's cancer death 8 months ago, and the movie meant more to me having seen it years before her death and them months after it. it's also about how our perception of time can be out of kilter. that can be frightening unless you just let it go and don't worry about it. i am trying to find ways to slow down my perception to time passing right now. one way is to have no electronics one hour before bed. i just putter around and do little chores.

Post a Comment