World War II left a lasting impact on a lot of filmmakers, for obvious reasons, though there seems to be a particularly special connection to wartime stories for European directors who lived in occupied nations. Many French directors have looked back at the Resistance and tried to make some sense of what happened as well as celebrate the heroic individuals who fought the good fight, in much the same way that some Japanese directors would later confront the post-War American occupation through film. Less often covered, however, at least in my cinematic experience, is the period during the war when Germany had set up camp on Italian soil. Last year, when I reviewed Roberto Rossellini's Era notte a Roma, I was not only surprised by the subject of the story, but also by the famed Neorealist's honest depiction of his own people. In one scene, one of the foreign soldiers asks why no Italian he meets is ever in favor of the war, because if it's true no one was behind it then it never should have started, and the response is that citizenry was more than willing to sway with the wind. When the war was good, it was popular; when it was bad, it was never popular. It's an all-too human response, I suppose. This scene also came to mind when I recently saw an episode of This American Life

A year before he made Era notte a Roma, Rossellini tackled related material in his controversial box-office hit Il Generale Della Rovere (1959)--though even that had not been his first time examining the internal struggle of occupied Italy, as fans of his breakthrough Roma, città aperta

Il Generale Della Rovere is the story of Emanuele Bardone, a con man played with believable salesmanship by Vittorio De Sica, best known as the director of Bicycle Thieves and Umberto D. Bardone is all things to all people. In the opening scene of the movie, he ingratiates himself to a Nazi Colonel by the name of Müller (Hannes Messemer) by telling him that unlike his fellow Italians, he thinks the war is a good thing; when speaking to those fellow Italians, however, he is far less kind about the Germans. Bardone's latest hustle requires him to play both sides. Having found a willing deskbound sergeant (Herbert Fischer) to go along with his scheme, he solicits bribes from families that have a relative in Nazi jails, skimming off the top before he passes the cash along for promises that the accused won't be shipped to Germany. Whether these promises are carried out is of little concern to Bardone as long as he can string the suckers along and keep paying for his gambling habit.

Or so we would at first believe, but Bardone is a difficult guy to figure out. It's never clear when he's being honest, and so, as part of the audience, it's hard to differentiate his true intentions from the game he runs. Perhaps he's so caught up in it, he can't figure it out either. He's willing to rob one girlfriend (the luscious Giovanna Ralli) to keep his con going, but not another (the equally luscious Sandra Milo), proving that there are people in the world whom he really cares for. When he is eventually caught, Bardone makes an impassioned speech about the burden of his task and the hope he couldn't bear to destroy, and he sure sounds like he means it. Could he really care for them all, could be believe in what he's doing? It's possible. Still, it's a lot like listening to Bernie Madoff talk about how he wanted to stop thieving but had dug himself too deep to ever get out of the Ponzi racket he'd set up. Any sensible person would think that all one has to do is at some point stop taking the money and start giving it back.

Bardone isn't taken down by his own greed so much as he just picks the wrong mark. Though the Fassio family looks like a good bet due to their obvious wealth, Carla (Anne Vernon), the wife of the arrested man, never really believes that Bardone is any kind of saint, and when facts get in the way of his lies, she isn't afraid to turn him in. This puts Bardone in the custody of the aforementioned Colonel Müller. Having problems of his own, Müller realizes that they are ones that Bardone's particular talents could solve. A recent attempt to capture the renegade Generale Della Rovere when he snuck into Italy to join the partisans was botched by Müller's soldiers and the Generale ended up dead. More valuable as a living asset, Müller convinces Bardone to go to prison in Della Rovere's stead so that the Germans can use the folk hero as a bargaining chip. The plan continues to morph when the Resistance leader codenamed Fabrizio (Giuseppe Rossetti) is believed to be amongst a group of men recently picked up in a raid. If the fake Generale can uncover which of the jailed is Fabrizio, he will be given a fat wad of cash and safe passage to Switzerland.

Pretty much from the moment he enters his prison cell, Bardone starts to become aware of how far out of his own control his life has swerved and has to face the gravity of the scams he's been pulling. The walls of his cell are covered with the last words of the four men who previously inhabited it. Their expressions of futility and acceptance and farewells to their loved ones could be notes for any of the families he took money from. He also must deal with the fact that the men all around him are in that prison for a reason: because they believed in something. Not only is he in there pretending to be a hero he most certainly is not, but he also has up until this point believed in no one but himself. Nobody says it, but the irony is that Bardone is the only prisoner who is actually imprisoned for committing a real crime.

A fundamental question of literature from the middle third of the 20th century is the meaning of action. Writers like Hemingway and Chandler looked at themselves and, by extension, the people around them and asked, when the chips are down, what did I do? What did you do? This is an extension of the existential school of thought, and an idea largely associated with Albert Camus

As it turns out, this man was also a banker who reaped the rewards of the wartime economy. This puts him on par with Bardone, a man who set aside all principles in service of his wallet. The difference is that now Bardone is in the position to change his fate. Since he started pretending to be the Generale, he has started to assume that role, offering soothing words to his fellow prisoners when they ask for them and even taking command to calm them down in an air strike. The moral choice for him is whether he continues to only save his skin or he starts working for others, as well. Hell, even choosing to go along with Müller whole hog would be better than getting pushed around.

Bardone's transformation is a believable one for how it happens by degrees. There is no great epiphany, no shining light on the way to Damascus--even if Rossellini does actually use a small skylight to illuminate one of the final puzzle pieces in the con man's change. This is what makes the earlier ambiguity about the character's true motives, as well as De Sica's ability to play him as such a greasy chameleon, so important. If we had one strong opinion about what kind of a man Emanuele Bardone really was, then the lessons he ends up learning walking a mile in Della Rovere's boots would be pat. It would be like a sports movie where the chubby, nerdy kid goes from being the underdog to the hero of the big game. No mystery to the change, he was just pushed through training and into digging down deep so he could be part of the team. Bardone does what he does for himself, joins the cause by his own decision, realigns his moral code to fit what he has seen and heard rather than a grab at glory.

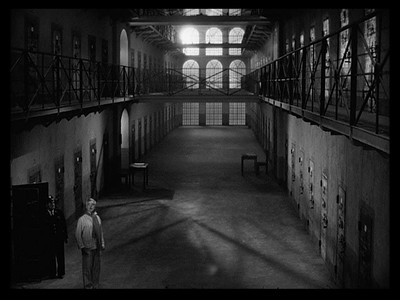

Unsurprisingly, Roberto Rossellini does a marvelous job at recreating war-torn Italy for Il Generale Della Rovere. From Bardone's cramped apartment, packed full with the accoutrements of a stage show (the charlatan's tools), to the bombed-out cityscapes, the environment is haunting and real. This is partially aided by some carefully placed newsreel footage showing the destruction and the cost of human life. Some argue that Rossellini was intending to draw a clear line between the real and the fake and emphasize the notion of film as invention with the difference between the stock footage and sets, but I didn't notice any line between when watching the picture. This is because the fiction is so vivid. Particularly memorable is the cold and imposing prison Bardone is sent to. I would have imagined Rossellini must have used a real jail, but it turns out it was a set built at Cinecitta. The director's production team deserves some extra credit for building such a harsh interior, so convincing in its cold and imposing design.

It's a fitting outer symbol of the harsh interior of Bardone, the moral prison that he has created for himself. The key to unlock this prison is also the key to unlocking his lost humanity, and it's the quest that drives Il Generale Della Rovere. He can clear his conscious with the same effectiveness as the frequent wipes Rossellni uses to erase the images on the screen and move the story along. It's that deftness of craft that makes this film truly great. It's why despite the heaviness of the subject matter, it all goes down so easy. A story expertly told, both in front of the camera and from behind it, Il Generale Della Rovere glides by. It's tightly wound drama, written without any excess, a perfect personal journey of one individual set against the backdrop of the larger world that he has tried to deny, but which he has affected and that has affected him in turn.

A new video essay by Rossellini expert Tag Gallagher explores the history behind the film, both the reality that informed the story and the stylistic approach the director employed in making the movie. Entitled The Choice, this fifteen-minute piece is an essential supplement, recounting the real-life inspiration for the story, the political climate that almost destroyed the picture, and Rossellni's personal reluctance to make the movie and how that affected the production. I don't quite agree with Gallagher's assessment of the sets used in the picture, but difference is the spice of debate.

That's Rossellini in the center with the handkerchief.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

No comments:

Post a Comment