Before Lars von Trier was part of the Dogme 95 movement, living by an avant-garde manifesto that was meant to chip away the artifice of filmmaking and adhere closer to the grittiness of real life, he was actually working on the opposite end of the spectrum. His early films were visually exciting, inventive, and challenging flights of imagination. This includes his 1991 post-War mindbender Europa (a.k.a. Zentropa), a Kafka-esque espionage adventure that tunnels its way into the bleakness of occupied Germany. Bureaucratic nightmares, rickety technology, false identities, and questionable allegiances all converge for a paranoid thriller that has as much to do with the treacherous landscape of the mind as it does our treacherous perceptions of history.

Leopold Tressler (Jean-Marc Barr) is an American sent to Frankfurt in October of 1945 to work alongside his Uncle (Ernst-Hugo Järegard) for the Zentropa Train Company. Leopold is to be a sleeping-car conductor, a clever symbol for the hypnotic journey he will soon be taking. His very occupation is that of ferrying passengers from one place to the next while they sleep. So, too, could all of Europa be a dream. We enter the movie under cover of night, a single light illuminating the train tracks that our eyes scan as the narrative voice of Max von Sydow plants the hypnotic suggestion that will transport us to Germany alongside Leopold.

Immediately upon landing at Zentropa, Leopold discovers a near impenetrable corporate system full of rules, regulations, and many a wheel that needs greasing just to get him started working. Each door he steps through requires another qualification, each person he meets further complicates the situation. Sometimes these discoveries seem part of a larger plot, sometimes they are simply extraneous wrinkles designed to push our hero further into the mire. He meets the Hartmann's, owners and operators of Zentropa--the weary father Max (Jorgen Reenberg), the gay son Lawrence (Udo Kier), and the mysterious daughter Katharina (Barbara Sukowa). Katharina first comes to Leopold on the train, claiming a fear of traveling through tunnels (paging Dr. Freud!), but then invites him over to dinner at the house, where she starts to peel away the layers of her outward persona. Katharina may have at one time been a member of the Werewolves, an insurgency of Germans trying to foil the American efforts to govern their country. Just as he is a man torn between his home country and his ethnic heritage, so is Leopold caught between the politics of a defeated Germany and the restoration/reformation efforts of the Allies. He witnesses a farce organized by the U.S. military leader Colonel Harris (Eddie Constantine) to exonerate Max Hartmann of any Nazi connections, but he is also duped by the Werewolves into making an assassination in the sleeping car possible. Leopold is so tangled up in this intrigue, he doesn't know whether he is coming or going.

Most of Europa is shot in black-and-white, evoking spy movies of the period, from Fritz Lang's pre-War homeland efforts to Orson Welles vehicles like Journey into Fear. Lars von Trier also uses exaggerated rear projection and subtle splashes of color, creating an effect that is a little something like Guy Maddin visiting Sin City

Europa is surreal in all things: technique, logic, and construction. von Trier's shooting style goes hand in hand with how the story develops, and the world that production designer Henning Bahs builds for Leopold to traverse gives it all shape. The Germany of Europa is like a wasteland, with bombed-out buildings sitting alongside labyrinthine constructs like the Zentropa worker's barracks. Interiors feel desolate, disconnected from the outside world by their decoration, at once looking like movie sets as well as the nightmarish, man-made products of war. In many ways, with the way his camera's movements homage Hitchcock and his audaciousness prefigures Baz Lurhmann, Lars von Trier is drawing a connection between the proliferation of pop culture--specifically, our obsession with movies--and our own interior anxieties. Our anguish over past misdeeds (the Nazis and World War II) comes cloaked in the iconography of old motion pictures, and these cloak-and-dagger images also bring up the lingering anxiousness of the Cold War and a fear of the unstoppable momentum of technological progress. Leopold is both a man of the world, fancying himself able to straddle two cultures, and an outsider, belonging nowhere, just as the 1990s were moving toward mass globalization where individual cultural identities were being celebrated even as the machine gobbled them up. And this was pre-Quentin Tarantino, before talking in pop cultural buzz phrases became de rigueur.

Within these echoes of movies past is Leopold's desire to belong, as well as his romantic yearnings. Katharina captures his heart even as she demands his trust. Here the "Werewolves" name is revealed to me more clever than maybe was immediately apparent: as a lover, Katharina is asking the same questions that one would ask as a monster or as a terrorist. Do you trust me not to hurt you? A commitment in any relationship begins with this question, whether it is articulated or not. And in movie fantasies, getting the girl and saving the day and coming out unscathed are all the same goal. The sticky web of romance and the sticky web of international intrigue? As Humphrey Bogart taught us, it's all the same thing.

Of course, Bogie wouldn't be as out of his element as Leopold is. The lie of the movie fantasy is that we'd be more confident in the midst of the concocted plot than we would be were it happening to us in real life. Leopold never knows what to do, is indecisive, and is subject to the caprice of those who would use him to their own ends. Caught between his desires and various regimented moralities, none of which seem right, Leopold could become hopelessly lost. To push the movie metaphor further, Katharina chastises him by saying that since he was not actually in the war, he is not really in a position to judge those who were. He hasn't lived it, he has only observed from afar, so how could he possibly understand what any of this means?

It's this accusation that pushes Leopold toward his final decision and puts the climax of Europa into motion. Leopold simultaneously becomes the voyeur and the man of action. In the foreground, he appears in color with a rifle; in the background, the black-and-white insertion of his own eyes watching him. I seem to recall similar eyeball imagery in Steven Soderbergh's Kafka (and, of course, Hitchcock's Spellbound), but in the explosive finish of von Trier's movie, he is evoking Orson Welles' movie of The Trial

Despite Lars von Trier's reputation as a difficult director, the refreshing thing about Europa's meta-narrative is that von Trier never steps so far beyond his audience that he looks back to smugly admire the intellectual distance that he has put between himself and the viewer. Rather, by wrapping this unconventional story in conventional trappings, he has created a comfortable zone for the viewers to appreciate what he is doing. The toys are familiar even if the playground is not. Thus, though Europa picks at our brain and challenges us to find our way through its maze, the way it keeps us guessing like any other wartime mystery doesn't make the puzzle-solving daunting. Rather, like the true masters of suspense, the pleasure is in the pondering, and thus it's all the more fitting that the entirety of the movie takes place all within the viewer's mind. A filmmaker is nothing but a hypnotist, after all, lulling you into a state where you believe that what you are seeing is real. (All the more fitting that von Triers' Hitchcockian cameo is as the lying Jewish collaborator who falsely exonerates Max.) To provoke, to intrigue, these are von Trier's goals, and though he would employ harsher methods in the years to come, Europa is no less stunning for the ease with which it goes down.

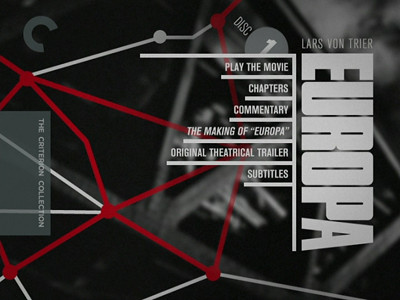

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full article at DVD Talk.

2 comments:

I am so glad this is out on a Region 1 DVD. I've waited years. I bought a DVD that supposed to be region free but was not. At least the Element of Crime was available in the mean time. :)

This is the most technically astonshing movie of the last twenty years. It is a joy to watch if your mind is alive.

Post a Comment