Ever since it was announced that David Gordon Green would be directing Pineapple Express, the next Judd Apatow-produced script by the Superbad writing team of Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg, there has been much speculation as to how the director would adapt his realistic style to a stoner comedy full of rude humor and action sequences. Over the last eight years, Green has made four movies, and though each one has moved him steadily closer to the mainstream, he has stayed pretty true to a particular aesthetic, a cross between 1970s maverick filmmaking and 1990s indie auteurism. There wasn't really a question of whether or not he could do it, but a question of how. What would a David Gordon Green comedy be like?

Well, I've seen Pineapple Express, and I think fans of the director will be pleased to see his naturalistic approach brought to bear on a completely unrealistic script, using his eye for realism to lend believability to a screenplay that would fall to pieces under a more fanciful commercial director. Green understands actors, he understands what a moment requires, and like a classic Hollywood director, I think we'll find that neither genre nor style can contain him.

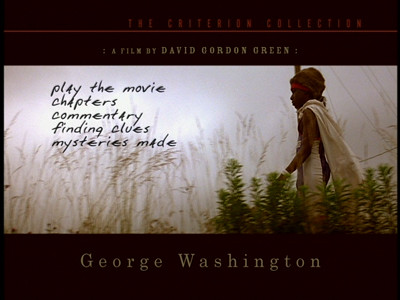

But that's really a review for another time and another venue (and one now available here). As the August 8 release date for Pineapple Express approaches, I thought it would be a good excuse to dig back into my collection and watch Green's 2000 debut, George Washington, again. I had always intended to do a joint piece on George Washington and Lynne Ramsay's Ratcatcher (1999). The proximity of their release on Criterion DVD caused me to originally watch them very close to one another, and in a lot of ways, they are the same movie even though they were made in two completely different parts of the world. Time permitting, I may still try to cover Ratcacher this week. (Edit: And have done so. Read the review here.)

Anyway, on to George Washington...

First off, no, it's not a biopic of our nation's first president. It's a bit daring to make a movie and call it George Washington and hope your potential audience won't be confused about what they are getting. I know I have a natural tic, which you just witnessed, to clarify as soon as I tell people about the movie. I suspect Green knew what he was doing, though, when he put that title together with the promotional iconography of the film. Despite the film not really being a critique of race relations in America, it does portray socioeconomic problems and how they affect people in the rural South one summer during the George H.W. Bush presidency. Green had to know that the juxtaposition of that name with the faces of his young black actors in his movie would raise an eyebrow or two.

The title is not without meaning in the context of the movie's narrative either. The focal character of George Washington is George Richardson (played by Donald Holden), a 13-year-old boy whom we are told dreams of being President one day. It's a passing mention by the narrator in the beginning of the film, and it doesn't come up again until the end, when the same narrator tells us of George's future plans to save the people of America over a collage of images that include Revolutionary War drawings, Sitting Bull, and President Washington himself. It's the payoff of other points in the movie where we see that George wants to be a part of the bigger picture. Not in some hokey sense where he is going to petition the mayor of his town or even write a letter to President Bush the First (though he does hang the man's toothy portrait on his bedroom wall) and end up on Oprah because of his patriotism; no, it's that he sees something beyond the borders of the rundown town where he is growing up, something he wishes he could join. Call it opportunity or the American Dream, call it the audacity of hope. After the 4th of July parade, George goes to the man who played Uncle San and tells him he was his favorite part of the procession. George isn't speaking to the man in the costume, he sees the icon behind it.

All of the children in the film have similar dreams to George's. For instance, the young girl Sonya (Rachael Handy) who hangs with the older boys is always stealing cars, despite apparently having nowhere to drive. 12-year-old Nasia (Candace Evanofski) dumps her boyfriend Buddy (Curtis Cotton III) because he isn't mature enough, even though he is a year older than she is, and she tells her girlfriends that if they ever want a good man they have to go look someplace else. Not that the men of the town have much of a chance to aspire to anything more. Most of them work down at the railyard, watching the trains go in and out, but never being able to go themselves. The poverty on display is staggering, the abandoned and rundown buildings almost looking like sets from an apocalyptic sci-fi movie or a post-war picture. All the more heartbreaking to consider that Green shot on real locations in North Carolina, and so these places actually exist.

The kids end up playing in what looks like an abandoned zoo, a surreal setting that ends up being a subtle metaphor. Such is the state of the cage that is meant to contain them. There is a sense of abstraction all around, that these children are stuck in some kind of pseudo-reality. Buddy even dons a lizard mask and performs on a stage at a theatre long since shut down, dramatically reciting a soliloquy asking that God not forget him and his brethren entirely. (When he is spotted by the affable Rico Rice, played by Green perennial Paul Schneider, Rico asks, "Is that the Bible or Shakespeare?" It's a smartass question, but meaningful. Just what kind of drama are you in, kid? Sacred, profane, or somewhere in between?) It's an ironically nostalgic speech, recalling a time when the speaker walked with God and enjoyed his blessings. For a boy Buddy's age, when would these halcyon days have been? Elementary school?

It is, of course, a ministration of God's favorite whipping boy, Job, who refused to give in no matter what maliciousness his Lord visited upon him. It's the indicator that Buddy is the center of things, his finger in the dam that holds back despair. Just as such a heavy speech is ironic coming out of his mouth, it also is ironic that the one boy who doesn't really want to leave, who is content being with his friends and really just wants Nasia to treat him right and not hook up with George, ends up being the catalyst to change everything and make the others consider options beyond what has been given to them.

One day while out playing, George, Buddy, Sonya, and the giant of the group, Vernon (Damien Jewan Lee), are playing in the bathroom at the zoo. They start hazing Buddy, and after Buddy shoves George too hard, hitting the boy's head, George lashes back. For much of the movie, George wears a helmet due to a condition where his skull is soft like a baby's, and he is not supposed to get it wet or suffer any heavy blows. Angry, George knocks Buddy roughly toward Vernon, and Buddy slips, bangs his head, and dies. (More irony for Buddy, alas.) Rather than just tell people what happened, the remaining kids try to hide the body.

How this act affects them is the focus of the second half of George Washington. Both Sonya and Vernon go through a bout of Dostoevskian self-doubt and question the entirety of their moral belief systems. Sonya continues to spin her wheels in the end, but Vernon's soul searching leads to some particularly poignant soul expression. Working with largely untrained actors, it's amazing that David Gordon Green, as a first-time director, was able to get these kids to open up the way they do. Vernon's speech about dreaming of a world where he can be at peace, alone and unbothered, free to do as he pleases, a world where Buddy has not died in a game he was participating in, strikes hard. The way the various wishes rattle off the boy's tongue with barely a pause between them gives the moment an emotional honesty that would not have been present had the actor given it a more "professional" line reading. The strength of his desire is why Vernon is the only one who is able to board a train and get out of there at the end, reminding me of a fictional touchstone in my life, Sherwood Anderson's Winesburg, Ohio

The evolution of this movie's George, however, is its own bizarre beast. Shortly after the incident with Buddy, George finds another boy face down in a swimming pool, and despite his condition, George jumps in and pulls the drowning boy to safety, risking his own life. Heralded as a hero, and perhaps seeking to do penance, George dons a cape and Buddy's old wrestling unitard and starts trying to do more good in the world, be it directing traffic or saving another life should the opportunity come along. In some ways, he looks crazy, but in some eyes, including his admirer Nasia (also the film's narrator), it shows that he is a dreamer. Rico sees it, too, encouraging George to endure no matter what people might say. Despite being the town clown, Rico is really the adult version of Buddy, having advised that boy in his love woes, as well as trying to keep his community together by encouraging the rail workers to support their union. (The Quebecois could have used a guy like Rico in Mon Oncle Antoine.) Nasia's sister even dates him, apparently proving the younger girl wrong in that there are good men in their 'burg. (One must assume that Nasia also moves on, since as narrator, she has at least some time, perspective, and a venue through which she can express herself.)

When George Washington came out, David Gordon Green received a lot of comparisons to Terrence Malick. It's easy to see Malick's influence on Green's style--the beautifully composed shots of untouched environments, the disconnected female narrator, and the eschewing of more predictable narrative structures for something more ambling and poetic. Green and his editors, Steven Gonzales and Zene Baker, cut the movie to match the rhythm and pace of a hot summer's day. They capture that lackadaisical feeling of youth, when it feels like there is too much time and never enough to do, that the world has ceased turning altogether. In pursuit of this feeling, Green does end up creating George Washington's one major flaw, a sense of time being out of joint. There are only three days between Buddy's death and the movie's conclusion, and yet so much happens, it seems like many more. Then again, that could actually be intentional. Enough evidence of an elastic, molasses-like passage of time exists elsewhere in George Washington, that this could be Green's final wrinkle to create an overriding aura of separateness.

Having now seen George Washington again and pondered it in relationship to Pineapple Express, even I find myself asking how we got there from here. In all of Green's other films, including this year's staggeringly great Snow Angels, the writer/director is concerned with the same communities of people that form the heart of the American South, examining how they struggle to come together and to get by. I suppose it makes its own kind of sense, then, that his first movie disconnected from his own background, set in California instead, is about people who don't really have that community and amidst all the weed jokes and explosions, form one. Arguably, he's just trading one type of disenfranchised American for another, the Southern problems for a Californian one.

There is one moment in Pineapple Express, though, that is pure David Gordon Green, that even if you forget he is the man guiding the action, reminds you of who is behind the camera. Lost and on his own, James Franco's character breaks down in a park. It's a wide shot, and in the background, we see an odd-looking Mexican girl watching him. She is on the other side of a chain link fence, and she wears a one-piece bathing suit. The camera cuts to her, and the director of All the Real Girls

The Criterion release of George Washington comes backed with three short films, two from David Gordon Green's student days and one by actor Clu Gulager, the gunman who wasn't Lee Marvin in Don Siegel's version of The Killers. Made in 1969, A Day with the Boys inspired Green in terms of its visual style and the way it showed youngsters at play. It's a strange little film, but in terms of imagery, quite interesting.

Green's 1998 film Physical Pinball features several of the actors from George Washington, including Candace Evanofsky. It's a sweet coming-of-age story, shot and scored like a 1970s "After School Special." Candace plays a young tomboy growing up with a widowed father (Eddie Rouse, George's uncle in the main feature) who treats her like a son, encouraging her to fight, work on cars, and hustle at pinball. The setting for this short is fantastic, with the family living in a renovated school bus in an old auto yard. Again, Green creates a wasteland vibe, with cars upturned and hoods standing open. Physical Pinball finds the girl at the onset of puberty, and tells the story about how both her and her father accept her oncoming womanhood in a way that is emotionally resonant rather than being trite or cliché.

1996's Pleasant Grove has a much more direct lineage to George Washington. The relationship of the boy Garland with his dog and the character's soft skull are like rough drafts for very similar scenes with George. Eddie Rouse and Paul Schneider also play early versions of their future characters. Shot cheaply on video and rife with overacting, Pleasant Grove hints at the filmmaking talent but lacks the skill, making it more of a curiosity than Physical Pinball, which shows quite a bit of growth for Green in just two short years. Two more after that and George Washington had come to fruition. One interesting style choice that changed over the years: in this short, there is no other pre-adolescent characters, and so the boy narrates the film himself.

1 comment:

how much the price of dvd this film? where is the strore that sell this film, i mean (George Washington)

Post a Comment