True story: half an hour after watching Terry Gilliam's 1998 adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas this morning, I was walking down my street. As I passed a house where some contractors were working on a remodel, I overheard one of the contractors explaining to the other about the "Paul is Dead" conspiracy surrounding the Abbey Road album cover. "George was dressed as a gravedigger," he said, "and Paul wasn't wearing any shoes."

Clearly something is in the ether today. The Beatles released Abbey Road, the last album they recorded, in late 1969. Within a year, they were no more, arguably closing the door on 1960s pop culture, following the zeitgeist of the decade right down the tubes. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is set in 1971. The peace-and-love generation is long gone, and chaos only exists in its place. Hunter S. Thompson's story of tumbling into a drug-fueled rabbit hole of decadence and danger was a harbinger of the decade that was to follow. Like the dust cloud at the motorcycle race he is sent to Sin City to cover, the 1970s would be a brown maelstrom of disappointment and disaster. Political activism would give way to complacency post-Nixon, and music and fashion was becoming bloated and boring. Let's face it, if it weren't for its cinema, the 1970s would be a decade best left forgotten. Torch the records, send it away!

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was long considered an "unfilmmable" book. Like William S. Burroughs' Naked Lunch, it was a tome revered for the irreverent prose style and the author's willingness to engage with all things taboo, and without the quality of the former the latter was rather difficult to capture. Conventional narratives these are not, and it would take equally unconventional filmmakers to make a movie out of them. Luckily, David Cronenberg got his mitts on Naked Lunch [review], and Terry Gilliam, the former Python turned surreal fantasist, tackled Fear and Loathing.

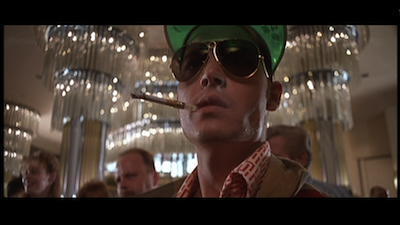

Johnny Depp stars as Hunter S. Thompson, who went to Las Vegas as a journalist, covering an epic motorcycle race in the desert under the guise of Raoul Duke. He would also stick around to report on a convention for law enforcement officers. Ironically, their chosen subject was stopping narcotics. Thompson is a notorious druggy, and he spends the entirety of this movie hopped up on some chemical concoction or another. Along for the ride is his "attorney," the larger-than-life Dr. Gonzo, played with pure animalistic chutzpah by Benicio Del Toro. The actor gives a purely physical performance, ditching actorly mannerisms for phlegm and sweat. He is perpetually clearing himself of some sort of bodily substance, and his character has a sinister bend that is truly disturbing. By juxtaposition, Thompson is a cartoon character, and Depp plays him as such. As a performance, it is definitely one extended impression of the real deal, but Depp approaches Thompson's contrived personage with the same honest intensity as, say, Robert Downey Jr. taking on Charlie Chaplin [review]. It's less an act than it is sculpture: the karate chops and whistles chip away at the artifice until it turns into something absolutely authentic.

Plot seems irrelevant in a discussion of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The movie's script went through various permutations, including a pass by Repo Man

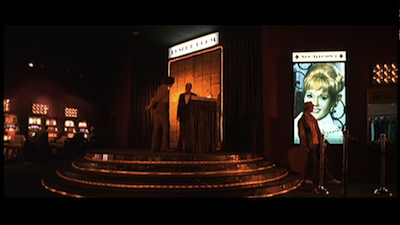

It's an interesting view of Las Vegas, taking us down its glitzy ladder rung by rung, going from its most surreal heights (a version of the kiddy casino Circus Circus) to this rundown, all-too-earthly greasy spoon. It seems to me that the key to the material is in understanding that the city itself is a trippy place, that the drugs are almost a tool for comprehending its garishness. No matter how weird the hallucinations get, Vegas can match the nightmare horror for horror. Visually, Gilliam and his team make tremendous use of the city's neon landscape. A driving montage down the strip uses rear projection and cutaways to melt and bend the surrounding signs and advertisements. Overdone hotel wallpaper and carpets come alive and swallow the patrons. Cinematographer Nicola Pecorini (The Order

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is nearly formless in its construction, though it solidifies over each selective viewing. To carry the drug metaphor, you build a kind of tolerance, gaining an ability to maintain the more you partake. Though I wouldn't have said so when it was first released, I'd hazard to call it Terry Gilliam's most together movie. Not necessarily his best, but possibly the one where he is most in command of the elements. For all the bedlam depicted onscreen, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is meticulously choreographed. Many of the scenes of Gonzo and Thompson wandering through the casinos while going off their heads play for extended lengths without much cutting. In these, they are each performing independent actions, including interacting with crowds of extras. Sometimes it's super complicated, like the hotel bar when they first get to town, just before all the other drinkers turn into lizards; other times, it's more simple. When Gonzo argues their way into a Debbie Reynolds concert, Thompson stays by himself, doing more drugs on the sly. Gilliam keeps the shot wide and lets the actors move around the frame. You could watch either of them do their thing, they are both doing something interesting, and yet it also works perfectly in tandem.

Naturally, with an experience like Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, there is no real exit, no grand conclusion to be had. The trip ends--in both senses of the word. The vacation is over, the vacationers have to come down off of the high. Yet, Gilliam gives us a satisfying wrap-up anyway. In his way, he has contained the chaos, and so there is a relief in making our way back out of it. Rubber hits the road, and Hunter S. Thompson heads back to Los Angeles, a smile on his face, remembering all the devils in the preceding details, having survived to return to some kind of perceived normalcy. And yet, that grin also says it's never going to be completely over: the craziest diamonds always shine on.

For a complete rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

Screen captures are from the DVD, not the Blu-Ray.

1 comment:

After this movie I play in online casino http://onlinecasinoguide.co.nz/ for the first time and it was fun. Sometimes my friends and I like to go gambling in casino near us. Good place and cheap

Post a Comment