Yasujiro Ozu is arguably the first Japanese master of cinema. Beginning his career as a director in 1927, a decade before Akira Kurosawa got his start, the filmmaker established a penchant for well-manicured family dramas early on. He made eighteen films in the silent era (a handful of them are featured in an Eclipse boxed set), and his 19th film, 1936's The Only Son, was his first talkie. As if to show off how advanced he was, he even included a scene where the movie's titular son takes his mother to see a Finnish film in Tokyo, explaining to her that movies with sound are the latest rage. In that self-reflective moment, Ozu was announcing his entry into the modern era.

The Only Son is the first of a double-dose of films featured in a new Criterion double-set showcasing two of Ozu's formative family stories. It proves to be an auspicious debut, telling a quiet tale that shows a confidence in the new technology. The Only Son doesn't suffer from the same problems of other early sound pictures. There are no awkward silences or scenes of actors standing around trying to figure out what to do. Rather, Ozu already shows as much control for this new technique as he did silent films. His dialogue is well-chosen and the pauses are natural, befitting a story of disappointment and expectations deferred.

Ryosuke is an only child living with his widowed mother (Choko Lida) in a country town. When the young boy (played in the first scenes by Masao Hayama) lies to his teacher (Chishu Ryu) and tells him he is going to middle school, he shames his mother into sending him for real, despite their finances not really allowing it. Jump ahead to the mid-1930s, and after years of toil, the mother is finally going to visit her adult son in Tokyo, where he moved to finish his studies.

When the woman arrives, she finds things are not as she expected. Ryosuke (now played by Shinichi Himori) has given up a job at City Hall and is now a night school teacher. He also has a wife (Yoshiko Tsubouchi) and a baby boy. These are developments he has kept a secret from his mother, and they form a division between them. There is a gap between the vision the woman had for her child and what he has become. What follows is a series of sorrowful exchanges where dissatisfaction is expressed, sacrifices are revealed, and the division between expectation and reality must be traversed.

Ozu is not concerned with the "big" moments or histrionics. There is no shouting in The Only Son. Rather, the director understands the power of measured expression. Working from a script by Tadao Ikeda and Masao Arata, which was actually based on a story by the director, he keeps the drama at a level volume. It's the tiny things that matter, you see. To emphasize this, Ozu often lets everyday objects dominate his tight frames. A rolled up sleeping mat, a framed picture--these are the things that fill our day to day, and somehow they anchor us. The actors subdue their emotions, observing a tightly wound social etiquette that only needs to unravel a little to unleash a flood of emotion.

The Only Son ends somewhere between renewed hope and tired defeat. A random accident gives Ryosuke's mother an opportunity to see the kind of man her son has really become. She is satisfied that he has a tender heart and a good start on a family of his own, but at the same time, he discovers new reasons to please her. In the final shots, Ozu shows us that life will go on, but there is also a deep exhale attached to it. Another long day closes, but is there any guarantee that tomorrow will bring new opportunity?

There Was a Father was made six years later in 1942 and under entirely different conditions, but it makes for an interesting companion piece to The Only Son. There are some thematic overlaps and narrative parallels between the two movies, even getting as specific as the teachers in both giving the same geometry lesson to their classes. In this film, rather than the relationship of a mother and her son, it's the paternal bond that Ozu is exploring. Chishu Ryu returns, this time playing a school teacher who, after a tragic accident on a field trip, decides to abandon teaching life and instead pursue work with less responsibility. He eventually splits with his son, Ryohei (played as a child by Haruhiko Tsugawa, as an adult by Shuji Sano), leaving the youngster with his uncle in their home town while he goes to Tokyo to earn money to further Ryohei's education. The plan was to reunite and live together again once Ryohei finished college, but he gets a job assignment away from the city, keeping the pair apart even longer.

By the time Ozu made There Was a Father, the Japanese government had started taking more control of all aspects of the country's industry. Films were subject to review by the ruling powers, and movies that promoted a positive message were encouraged. There Was a Father was made under these restrictions, and the result is less of a satisfying cinematic narrative and more of an educational film. It's the strangest kind of propaganda, full of speeches from Ryu about one's duty to one's work, whatever that work may be, regardless if the job is less than ideal. The big message of the picture is that sacrifice is good, and everyone is required to make their own.

For the There Was a Father script, Ozu and Ikeda were this time joined by Takao Yanai, though it's impossible to point a finger at any of the three and blame him for the tepid writing. The movie is devoid of any real drama. All the characters are pleasant, and they accept their lumps with a smile. There is no conflict beyond the separation anxiety, and maybe a little debate about when Ryohei will get married. That's really it. There Was a Father is mainly a talking heads film, with the characters discussing their hardships in order to agree that it's good to have them.

In less stylish hands, There Was a Father would probably be unwatchable. As far as Yasujiro Ozu's filmography is concerned, this is a lesser picture (and easily my least favorite of any I've seen), but it's still an Ozu picture. The actors are so likable and the delivery so charming, even though nothing much goes on, it's still fairly agreeable medicine. Honestly, after seeing it, I'm not surprised Criterion decided to couple it with another movie, it wouldn't be much of an item on its own. Thankfully, they found a main dish that that this side goes together with really well.

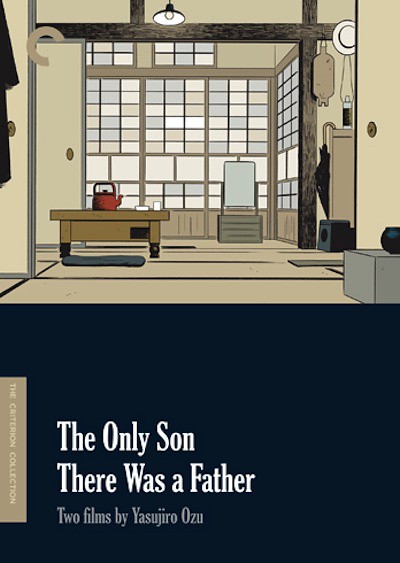

The Only Son/There Was a Father: Two Films by Yasujiro Ozu comes in a handsome package. Each disc has its own plastic case and individual interior booklets with photos, credits, chapter listings, and new informational essays about the films. These fit in a high-quality, side-loading box. The box and both the movies are decorated with illustrations by renowned comics artist Adrian Tomine. The drawings are delicate and lovely, just like the movies. Tomine is a good choice for the set, as his series Optic Nerve is at its best when depicting small moments in the same way that Ozu does. It's the emotion in between the huge events that is the most poignant in his stories, and though he is more cynical than Ozu, they share a similar approach to drama. One could easily imagine Tomine's protagonists wishing they could belong to a social order as stable and idyllic as Ozu's, where people have problems yet aren't crippled by them.

For a full rundown on the special features, read the full review at DVDTalk.

1 comment:

It's the effing point of most Ozu's films that there's no drama. LOL the ignorance. There Was a Father is one of his best.

Post a Comment